Clive, Robert, Baron Clive of Plassey, AKA ‘Clive of India’

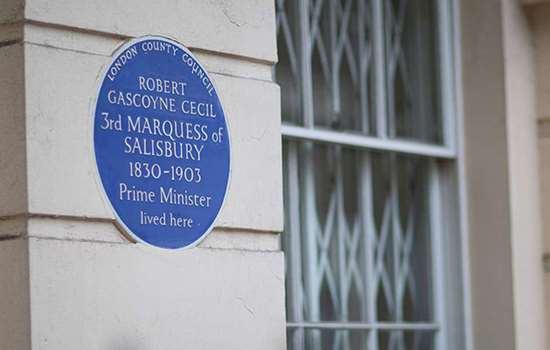

Plaque erected in 1953 by London County Council at 45 Berkeley Square, Mayfair, London, W1J 5AS, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Soldier, Administrator

Category

Armed Forces, Politics and Administration

Inscription

CLIVE of INDIA 1725–1774 SOLDIER AND ADMINISTRATOR lived here

Material

Ceramic

Robert Clive, later Baron Clive of Plassey, played a founding role in the establishment of British rule in India. This, and his conduct as the virtual ruler of Bengal, made him an extremely controversial figure in his lifetime, and he continues to be so today.

Clive and the East India Company

Born into a Shropshire gentry family, Clive was prone to fighting as a boy, and was variously educated in Cheshire, London and Hertfordshire. He was appointed to serve as a clerk for the East India Company Madras, arriving there in 1744. Not long after, in a depressive episode, he attempted suicide with a pistol that refused to fire: ‘It appears I am destined for something, I will live’, was his reported reaction.

Clive’s reputation as a military commander was made by his leadership during the siege of Arcot (1751) and at the battle of Plassey (1757), where his army defeated French forces and those of the Mughal emperor’s viceroy.

In the folklore of the British Empire, this was seen as avenging the ‘black hole of Calcutta’ – an episode the previous year in which British prisoners had suffocated. The politician Pitt the Elder, called Clive a ‘heaven-born general’, and he was made Baron Clive of Plassey – though even Lord Curzon, a later admirer, described the encounter that gave Clive his title as ‘in truth scarcely a battle’. Through the East India Company, Clive became the effective ruler of Bengal, and the title of its governor was conferred on him in 1764.

The Bengal Famine and Trial

Clive amassed a huge personal fortune in India – the equivalent to over £30 million today – and following his return to England was the subject of a parliamentary enquiry into corruption. The policies of the East India Company under him – in particular a punitive land tax – were also held responsible for exacerbating a disastrous famine in 1770, which killed ten million people, or about a third of Bengal’s population.

Colonel John Burgoyne, who chaired the investigation, described Clive’s actions as crimes that would have shocked human nature. ‘I stand astonished at my own moderation’, was Clive’s defence of his fortune-hunting; Parliament rebuked him for it, but asserted that he ‘did, at the same time render great and meritorious service to this country’. Nirad Chaudhuri, a recent biographer of Clive, has noted that ‘England could not retain the stolen goods if they called Clive a thief’.

Robert Clive died the following year at his home in Berkeley Square. Prone to depression and to physical illnesses, it was widely thought that he either took his own life or accidentally overdosed on opium, on which he had become increasingly reliant.

Posthumous reputation

Clive’s reputation at his death and in its immediate aftermath was poor, and the history of the British in India by James Mill (1817) did not cast him in a good light. The historian Thomas Babington Macaulay was more positive in 1840, but still said he had ‘a bad liver and a worse heart’.

But as India came under the direct sway of the British crown, the patriotic myth of Clive began to take shape. A statue was raised to him in his home county in 1860. He was the subject of an 1880 poem by Robert Browning, and Clive became popular as a given name.

In 1907 Lord Curzon suggested that Clive ought to have a memorial, for having laid the foundations of an empire ‘more enduring than Alexander’s, more splendid than Caesar’s’. Just 40 years later that empire was gone, but the statues of Clive in Kolkata, London and Shrewsbury remain.

Most recent historical views of Clive have been negative: Simon Schama has called him a ‘sociopathic, corrupt thug’. Defences of him tend to be relativist: that he was a product of his time, and of the mercenary East India Company that he served, or no worse as a ruler than the Mughals that he displaced.

Blue plaque

A plaque to Clive was proposed in 1908, but the owner of 45 Berkeley Square – a descendant – declined it. One finally went up in 1953, two years before the condition of ‘a positive contribution to human welfare and happiness’ was written into the plaque scheme’s awarding criteria. It might be said that the human welfare to which Clive chiefly contributed was his own: his exploits bought him estates in Surrey and in Ireland, and the grand townhouse on which the plaque sits. This dates from the 1740s, and Clive took up residence in 1761, initially as a tenant of Lord Ancram, though he eventually bought it for £10,500.

The plaque is rectangular, to better fit the building’s stonework, and calls him ‘Clive of India’, as he was once widely known. He was not, in fact, ‘of India’, but of Shropshire, and his relationship with the sub-continent was essentially one of exploitation.