GILLIES, Sir Harold (1882–1960)

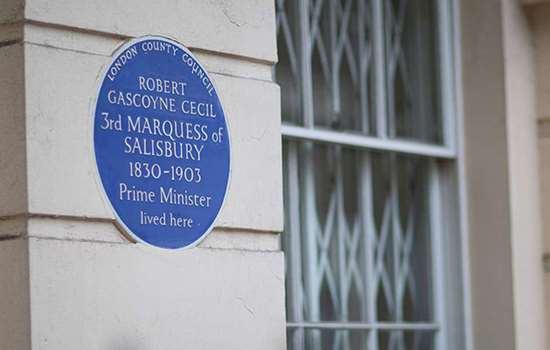

Plaque erected in 1997 by English Heritage at 71 Frognal, Hampstead, London, NW3 6XY, London Borough of Camden

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Plastic Surgeon

Category

Medicine

Inscription

SIR HAROLD GILLIES 1882 – 1960 Pioneer Plastic Surgeon lived here

Material

Ceramic

Plastic surgeon Sir Harold Gillies developed groundbreaking techniques for reconstructing damaged faces. The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography states that ‘The art and science of modern plastic surgery, in Britain and New Zealand in particular, owe their origins mainly to him.’ A plaque commemorates him at his former home, 71 Frognal.

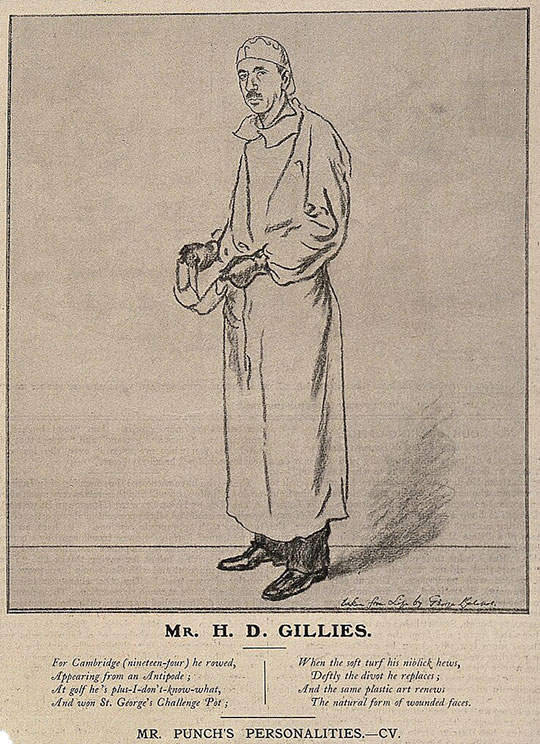

Harold Delf Gillies was born in Dunedin, New Zealand in 1882. Although a childhood accident had made it difficult to move his elbow for many years, he keenly participated in sports. He qualified as a doctor in 1906, was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1910, and became an ear, nose and throat surgeon. Gillies was admired for his skill at golf, and it was this standout ability that led Sir Milsom Rees to hire him. Gillies subsequently missed an appointment with Dame Nellie Melba because he was in a golf championship.

First World War work

In 1915, Gillies volunteered to serve with the Red Cross. He worked with dentist Auguste Valadier, who had established a unit for jaw work, and became fascinated by facial surgery. After observing renowned plastic surgeon Hippolyte Morestin in Paris, Gillies persuaded the British Army Surgeon General to allow him to establish specialised facial surgery wards in Aldershot. The War Office were uninterested in his idea for giving people special facial injury casualty tags, so he bought some labels himself from a stationer and sent them out with instructions. People soon began to arrive with his labels.

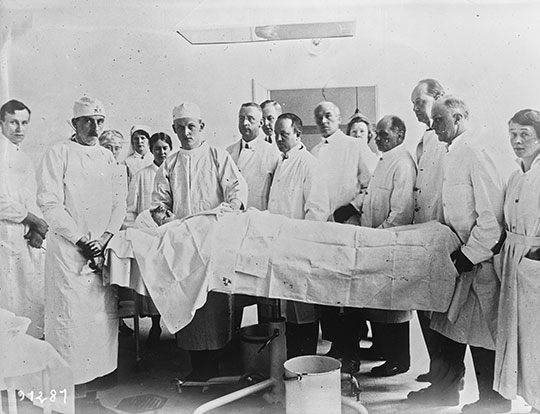

Two thousand casualties arrived at his ward with face and jaw wounds after the Battle of the Somme alone. Soon afterwards, Gillies’ team moved to Frognal House, a converted old mansion in Sidcup, Kent, which opened in June 1917 and became known as the Queen’s Hospital.

There, Gillies realised his vision for a place where expert staff from around the world were able to make technical advances by working in proximity. He was an early advocate for a multidisciplinary team and brought together anaesthetists, dentists, physicians, radiologists, technicians, artists (including surgeon-turned-artist, Henry Tonks FRCS), sculptors (such as Kathleen Scott, widow of the Antarctic explorer) and photographers. They developed many new techniques, focussed on both functional and cosmetic improvements, and emphasised rehabilitation.

Gillies later recalled how the injuries confronting the team demanded that they rapidly develop new plastic surgery techniques. ‘This was a strange new art’, he wrote, ‘and unlike the student of today, who is weaned on small scar excisions and gradually graduated to a single hare-lip, we were suddenly asked to produce half a face’.

Later life and work

The teams disbanded after the war, many to set up their own specialist plastic surgery units, and Gillies wrote his acclaimed textbook, Plastic Surgery of the Face (1920). From 1921, Gillies lived at 71 Frognal in Hampstead, an unusual corner house with a round tower and turret on a site bounded by Redington Road and Oak Hill Park; the planting of the garden may make the plaque difficult to see. He was knighted in 1930 and his cousin Archibald McIndoe joined him in his work.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Gillies, McIndoe and their colleague Rainsford Mowlem were three of only four plastic surgeons in the UK. Gillies was responsible for setting up a network of surgical units across the country and headed specialist work at Park Prewett Hospital near Basingstoke. He was bombed out of his home in 1941.

Gillies continued to experiment and innovate after the war. From 1946 Gillies conducted a series of surgeries on Michael Dillon, the first phalloplasty done for the purposes of female to male gender reassignment. He also operated on Roberta Cowell in 1951, creating Britain’s first surgically created vagina.

Gillies founded the British Association of Plastic Surgery and was its first president. He documented cases using new colour photography techniques and films, and his second book Principles and Art written with D Ralph Millard was published in 1957. Gillies’ inventions, the Gillies tissue forceps and Gillies needle holders are still widely used today. He continued to work and teach until his death in 1960 at the age of 78.

Further reading

-

Andrew Bamji, Faces from the Front: Harold Gillies, The Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup and the Origins of Modern Plastic Surgery (London, 2017)

-

Lindsey Fitzharris, The Facemaker: One Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I (London, 2022)

-

Amy Kitchingman, ‘Transgender Pioneers: Roberta Cowell, Michael Dillon and Harold Gillies’, Thackray Museum of Medicine

-

‘Trans Pioneers’, Historic England (accessed 13 November 2025)