CLARKE, Joan (1917–1996)

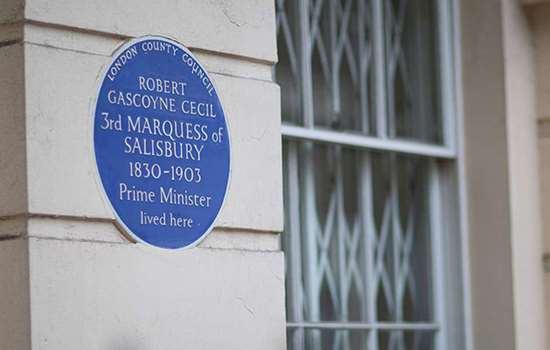

Plaque erected in 2024 by English Heritage at 193 Rosendale Road, West Dulwich, London, SE21 8LW, London Borough of Lambeth

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Mathematician and code-breaker

Category

Armed Forces, Collecting and Antiquities

Inscription

JOAN CLARKE 1917–1996 Code-breaker lived here

Material

Ceramic

Joan Clarke was a brilliant mathematician who had a remarkable career as a code-breaker for the British government during the Second World War and Cold War. She was the most senior of the few female cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, and the longest serving member of Hut 8, which cracked the German naval Enigma code.

She is commemorated with a blue plaque at her childhood home where she studied to become a talented mathematician, number 193 Rosendale Road.

Early life

Joan Elizabeth Lowther Clarke was born in Dulwich on 24 June 1917, the youngest child of the Reverend William Kemp Lowther Clarke and Dorothy Elizabeth Fulford. Joan was baptised at All Saints, Rosendale Road. She was educated at Dulwich High School for Girls and won numerous prizes, including the Elsie Clarke prize for mathematics in 1934.

The blue plaque at 193 Rosendale Road marks the home where Joan Clarke’s life was rooted for over a decade, and where she developed the love and knowledge of mathematics which would lead to her career as a code-breaker.

In 1936, Clarke won a scholarship to study mathematics at Newnham College, Cambridge. She achieved a double first and was awarded the Philippa Fawcett prize and the Helen Gladstone scholarship for a fourth year of studies, but had to wait until 1948, when women were finally permitted to graduate by Cambridge University, to receive her degree.

Bletchley code-breaking

After war was declared in September 1939, Clarke was invited to do ‘interesting work’ work for the Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. On her arrival in 1940, Clarke was immediately poached by Alan Turing, whom she had met while at university. In Hut 8, Clarke, Turing and the team worked on deciphering the code used by the German navy, which was generated by rotors in the Enigma machines scrambling letters. The naval codes were the toughest to crack.

Clarke became one of the ‘Seniors’ of Hut 8. She studied cipher texts punched out in long sheets of alphabetical columns to work out the probable right and middle rotor starting positions.

The capture of Enigma key tables and then a naval Enigma machine complete with rotors enabled Clarke and her colleagues first to decipher code and then speed up decryption. They worked round the clock in three daily shifts. Clarke streamlined methods so that even shorter messages with fewer clues to aid decryption could be deciphered.

The intelligence provided by Hut 8 critically reduced the number of Allied ships that were being sunk.

Relationship with Turing

During spring 1941, Clarke and Turing spent time together outside Hut 8. Clarke was surprised when Turing proposed to her but agreed to marry him. He warned her that the marriage might not succeed on account of his homosexuality, but they remained engaged and visited each other’s families. After a holiday in Wales, the engagement ended, though their friendship survived.

D-Day and SOE

In 1942, a new Enigma machine was developed using four rotors rather than three, which thwarted Hut 8’s decryption and enabled German U-boats to attack Allied shipping convoys once more. Clarke deduced from intercepted code papers that the fourth rotor used the same cipher as the three-rotor system. Following Clarke’s deduction, the code was broken by her colleague Shaun Wylie and the flow of deciphered messages resumed.

Hut 8’s work intensified in the run-up to D-Day on 6 June 1944. They worked closely with Hut 10 to decode weather signals sent by the Germans and to support the increasing number of Special Operations Executive (SOE) operations and bombing raids preparing the way for the invasion.

In September 1944, Clarke became deputy of Hut 8; only two Seniors remained, but they kept the three-shift system.

Post-war life

After VE Day, Clarke remained on the GC&CS staff. In January 1946, she was appointed MBE. By April, she had transferred to RAF Eastcote in Hillingdon, London, where GC&CS was renamed Government Communications Head Quarters (GCHQ). Clarke worked in H division on the ‘Vanona’ project, decoding communications sent between Soviet agents.

In 1952, Clarke married Lieutenant-Colonel John ‘Jock’ Kenneth Ronald Murray, whom she had met at Eastcote. They left GCHQ due to Jock’s ill-health and moved to Crail, Scotland. Joan’s activities from this point are hard to discern, and it is possible that she still worked for GCHQ. The Murrays settled in Crail at the same time as the Joint Services School for Linguists was consolidated at the RAF base nearby, and GCHQ maintained a listening station nearby in Cupar, which intercepted messages from Eastern Bloc countries.

In January 1962, Joan and Jock were invited to return to work at GCHQ, which had relocated to Cheltenham. On their return, Jock had to go through vetting and a probation period, but no such checks applied to Joan, suggesting that she had never formally left the service.

Joan became a Principal in 1975. She formally retired in 1977 but continued working for another five years as a clerical officer. In 1982, Joan left GCHQ for the final time and promised to adhere to the Official Secrets Act for the rest of her life.

Later life

As the work of Bletchley Park became known to the public, Joan provided information for a biography of Turing. She co-authored an appendix about the Polish contribution to code-breaking published in British Intelligence in the Second World War (1988) and contributed a short chapter to Codebreakers: the Inside Story of Bletchley Park (1994).

From 1965 onwards, Joan researched the history of Scottish coins. She assembled a chronology of late medieval coinage and in 1986 she was awarded the John Sanford Saltus Gold Medal, the highest honour conferred by the British Numismatic Society.

Joan Clarke died on 4 September 1996, aged 79.