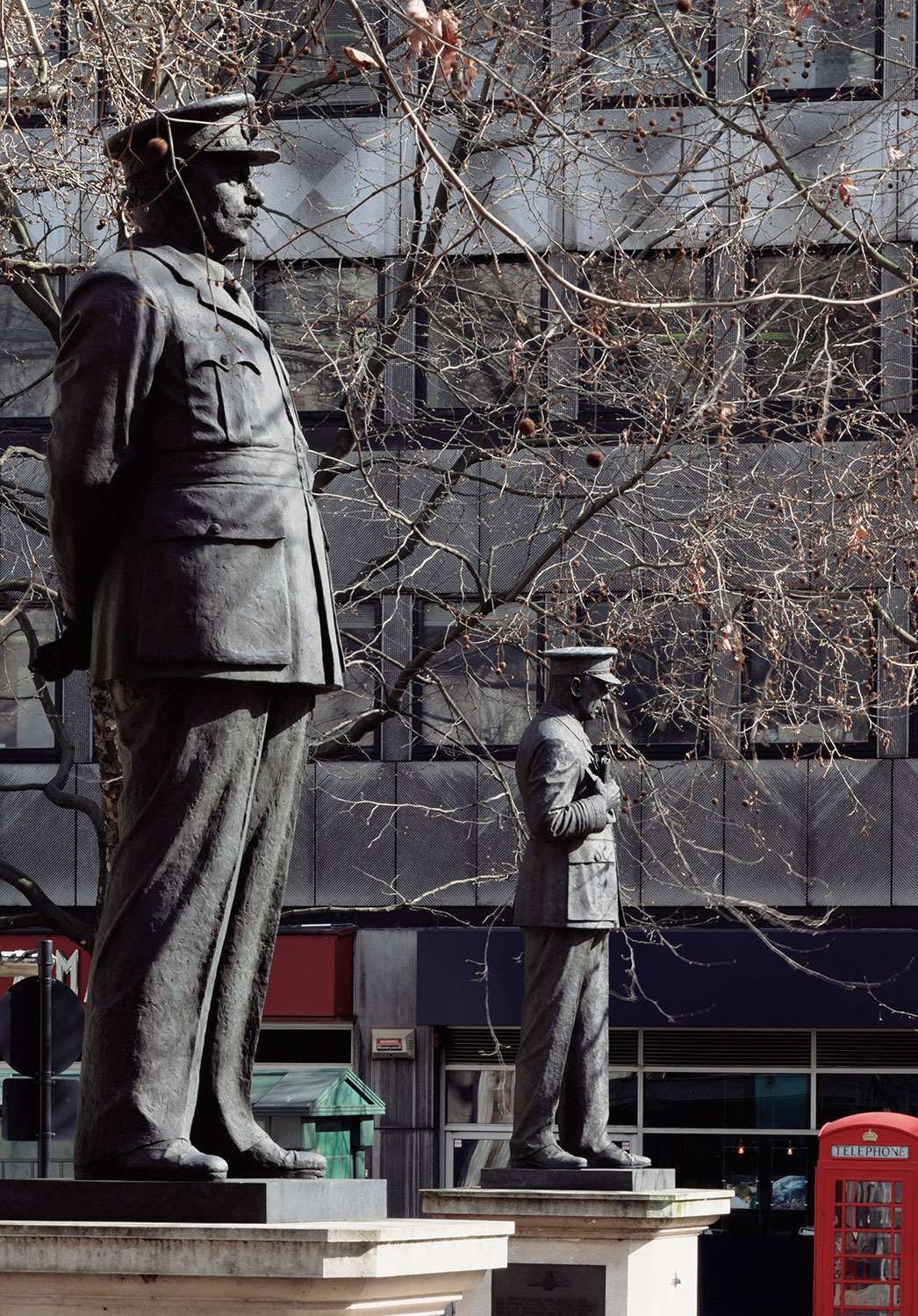

© National Portrait Gallery, London

From late 1915, Harris was a fighter pilot in the RFC, gaining five ‘victories’ (enemy aircraft destroyed) in France. In 1918, as a squadron leader, he transferred to the newly formed RAF, and later served in India, notably in Waziristan (now in Pakistan) during a campaign against a major tribal uprising (1921–2). Later in 1922 he was in Iraq, successfully flying the Vickers Vernon aircraft to support ground troops fighting Turkish and Kurdish forces. This included their improvisation as bombers, large-scale troop transport and casualty evacuation. He also pioneered night flying, target marking and accurate aerial bombing, emerging with a reputation as an efficient, innovative commander.

Back in England, in May 1925 Harris took command of a heavy bomber squadron (No. 58) at RAF Worthy Down, Hampshire, and his continued innovation and leadership contributed to his promotion to Wing Commander in July 1927.

As a Group Captain between 1933 and 1937, Harris had a desk job at the Air Ministry, part of a small team that developed air policy and the RAF expansion programme in the light of a growing German threat. Harris promoted the creation of a heavy bomber force to counter the expected German air offensive. From 1936, British re-armament began in earnest, and in 1937 came the formation of Bomber Command.

In May 1937, Harris returned to operational service in command of No. 4 (Bomber) Group – officially titled ‘Air Officer Commanding’ (AOC). After a short trip to America in April 1938 on a mission to procure aircraft, he went to Palestine (1938–9) during the Arab Rebellion. Here, as the AOC, he developed a policy of containment of enemy forces by bombing, to give time for ground troops to arrive.

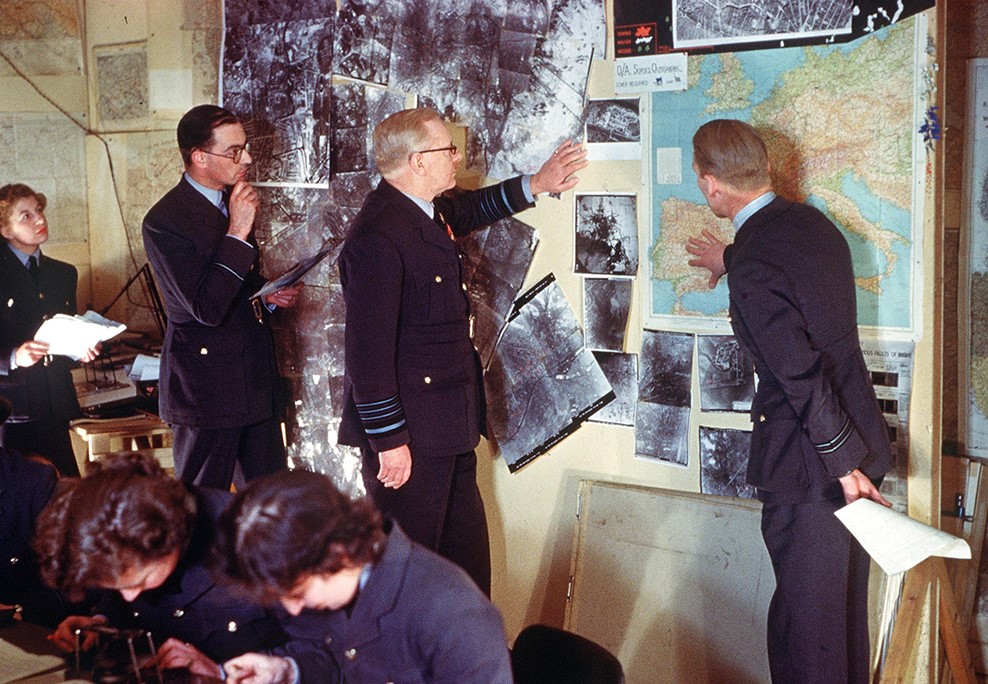

© Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

By July 1939, aged 47, Harris was back in England, and at the outbreak of the Second World War in September, took over as AOC 5 Group, one of five subdivisions of Bomber Command. Harris held this command until November 1940 and cemented his reputation as a leader who made vigorous efforts to improve the aircraft and conditions for staff in his command.

After another posting at the Air Ministry, and briefly as a liaison officer in the USA, Harris was appointed as AOC for all of Bomber Command in February 1942. He inherited a dispirited force, ill-equipped for its purpose. Slowly, systematically but doggedly in a climate where resources were fiercely contested, Harris improved everything, including the numbers and types of aircraft and the detailed operational training needed. Though like many senior officers he was seemingly aloof, stiff, and abrupt, he appears to have inspired great loyalty and respect from those who served him. Sir John Curtiss who served in Bomber Command during the Second World War later recalled of Harris:

…very few of us ever saw the man. But somehow his personality and his determination...he got across to us the feeling that if he asked us to do something, it was something that was really necessary to be done, and so we did it cheerfully.

By mid-1944, Harris had transformed Bomber Command into a formidable force. But it was an extremely dangerous job: of its 125,000 aircrew, 55,573 were killed in action – a massive 44.4%.

Bomber Command’s roles included minelaying, support of ground and sea forces, and bombing of military, industrial and economic targets. These included aircraft, munitions and ball bearing factories, transport infrastructure such as railways, marshalling yards and canals, and oil refineries. It also carried out specialist tasks – for example, the Dambusters Raid against reservoir dams in the industrial Ruhr area of Germany, assaults against V1 and V2 rocket sites, and massed attacks prior to and during the D-Day landings in June 1944.

© Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

But its biggest effort was in the bombing of German industrial cities, on occasions deploying over 1,000 aircraft, to destroy factories, resources, infrastructure, and workers’ housing. The aim was to reduce Germany’s ability to fight and to break the morale of its people. The programme became known as ‘area bombing’ as, for most of the war, technology did not enable high precision, especially when cloud often obscured the targets. In some raids, bombing caused firestorms and massive loss of civilian life, as in Hamburg in 1943 (45,000 casualties) and Dresden in 1945 (25,000 casualties).

Harris was unequivocal, blunt and uncompromising, remaining certain that the bombing of German cities would bring the war to an early close, even debating with senior staff to persuade them he was right. This strategy became controversial among senior officers and in government circles in 1945, as the war in Europe approached its end. Some, more senior than Harris, continued to support it; others thought that it was no longer necessary. A few who had supported the policy now wanted distance. Harris became the focus of criticism almost immediately because he was consistent and vociferous in the belief that targeting industrial cities would shorten the war and save lives. However, the strategic bombing of German cities was not initiated by him: it was a British War Cabinet decision, taken before Harris took over at Bomber Command, and in the aftermath of the Luftwaffe’s devastating bombing of Britain.

As part of Allied strategy, it may have shortened the war but not by breaking German morale or ending warlike production. It was effectively a second front that diverted enemy production onto defensive measures – anti-aircraft guns and fighters – thereby removing vital resources from the war on the ground.