© The Print Collector via Getty Images

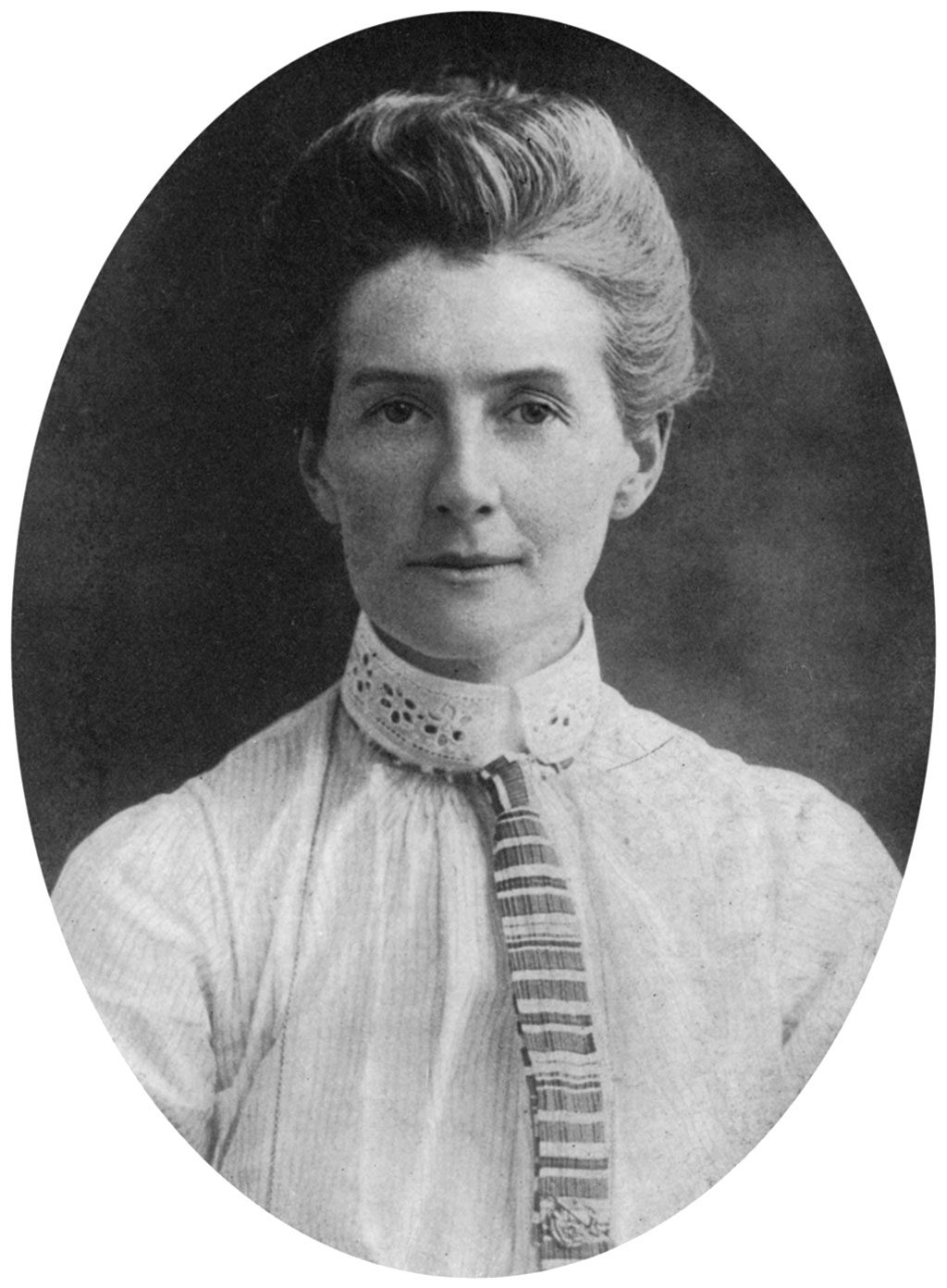

The daughter of a Church of England clergyman, Edith Cavell (pronounced CAH-vell) was born on 4 December 1865 at Swardeston vicarage in Norfolk. She was educated at home and later at schools in Somerset, London and Laurel Court in Peterborough.

Cavell showed a talent for drawing and a certain streak of independence: she was caught smoking at the age of 16, and complained to her cousin Eddy of the interminable length of her father’s sermons. She also told him, ‘Someday, somehow, I am going to do something useful. I don’t know what it will be. I only know it will be something for people.’

After school, Cavell became a governess, first in Steeple Bumpstead, Essex, then in Brussels. After six years in Belgium she returned home to look after her ailing father. She determined to become a nurse and worked in the Fountains Fever Hospital in Tooting, south London, before entering the London Hospital School of Nursing in September 1896. Here, the matron Eva Luckes – who was never lavish with her praise – wrote that Cavell ‘had a very self-sufficient manner which was very apt to prejudice people against her’.

© Hulton Deutsch via Getty Images

Upon qualifying, Cavell worked as a staff nurse at the London Hospital, after which she became night superintendent at the St Pancras Infirmary, then assistant matron at the Shoreditch Infirmary followed by St Leonard’s Hospital, where she improved the training of maternity nurses and inaugurated the practice of visiting newborns at home, which later became standard practice.

After a short spell as a matron in Manchester she returned to Brussels in 1907 to set up a nurses’ training school and clinic, the Berkendael Medical Institute, under Dr Antoine Depage, a Brussels surgeon. The school’s first certificates of competence were issued in 1910, and the state registration of nurses was introduced in Belgium not long after. In addition, Cavell became matron of a new hospital in the suburb of St Gilles. The role she played in raising nursing standards in Belgium has been increasingly recognised over recent years.

Cavell’s contemporary fame, however, was due to her activities during the German occupation of Belgium during the First World War. As part of a clandestine network, she assisted Allied soldiers caught by the rapid German advance to escape via neutral Holland.

Fugitive fighters were provided with fake identity papers and a place of refuge, of which Cavell’s hospital was one. Estimates of the number of solders she enabled to escape in this way vary from a few hundred to well over a thousand.

© Topical Press Agency / Stringer via Getty Images

On 5 August 1915, Cavell was arrested by the German authorities shortly after Philippe Baucq, one of the resistance network’s leaders, had been captured. She was kept in solitary confinement at the prison at St Gilles, admitted the substance of the charge against her – that she had assisted the enemy – and signed what amounted to a confession.

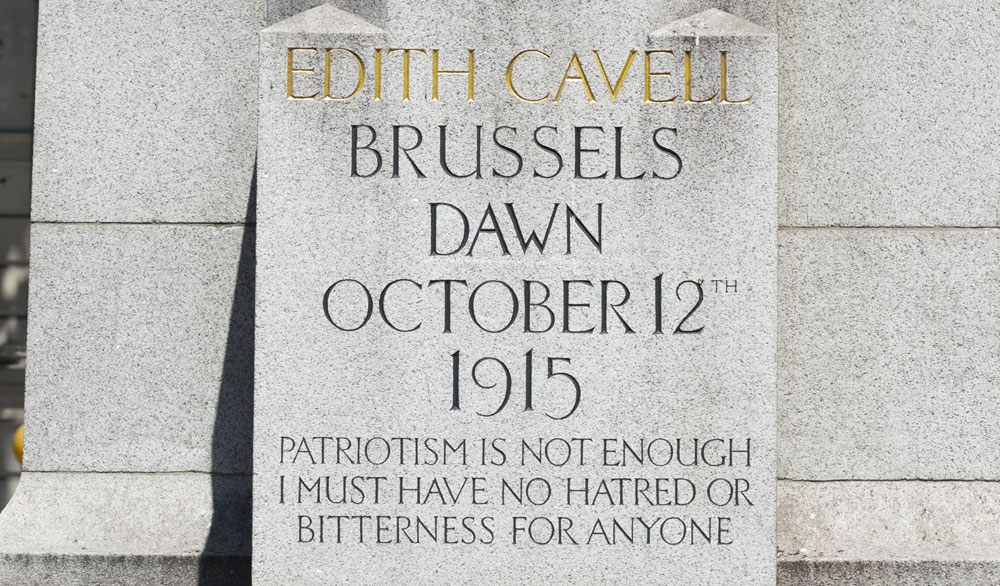

Cavell was among nine people court-martialled on 7 October 1915, and one of the five sentenced to death the following day. She and Baucq were the only two not to have their sentences commuted, and were both shot at dawn on 12 October 1915.

After her sentence was handed down, Cavell – a devout Christian – took her final communion with the Anglican chaplain, the Reverend H Stirling Gahan, and said, ‘standing as I do in view of God and Eternity, I realised that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.’

© Hulton Archive / Stringer via Getty Images

Gottfried Benn, the German medical officer present (later famous as a poet), stated that Cavell ‘went to death with poise and a bearing which is quite impossible to forget’. Her final moments were much mythologised: stories that circulated included that the Germans shot her at the dead of night; that she had swooned in front of the firing squad, and that her executioners had refused to carry out their orders.

The execution of a woman – a nurse, no less – sparked international condemnation, and was a propaganda gift to the Allies. The Kaiser himself acknowledged this by requiring that no death sentence could be carried out on a woman thereafter without his express permission.

© LMPC via Getty Images

One of Cavell’s biographers calculated that the number of UK army recruits doubled in the weeks following Cavell’s death. It has been cited, too, as a factor in shaping opinion in the United States, which entered the war on the Allied side in April 1917.

At the end of the war, Cavell’s body was removed from its burial place at the Tir National in Brussels and carried back to Britain. After a funeral service in Westminster Abbey, she was finally laid to rest in the precinct of Norwich Cathedral on 15 May 1919.

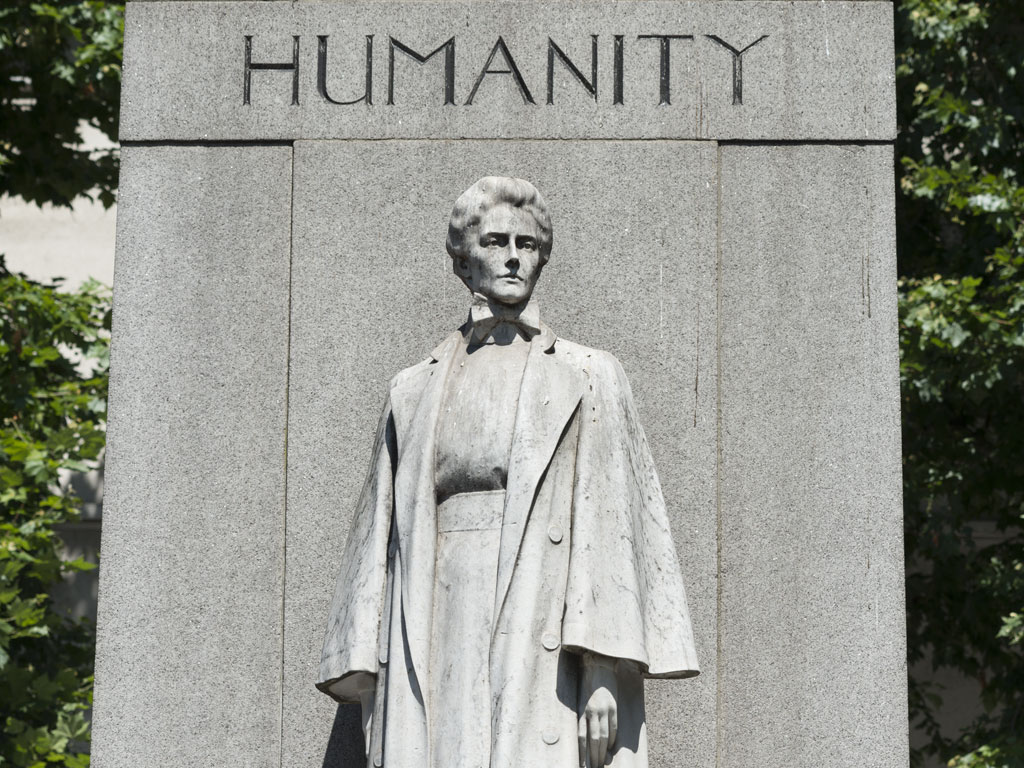

By this time George Bellows had depicted The Murder of Edith Cavell (1918) and her mass memorialisation was under way. One source counts eleven streets in London named after Cavell and reckons that there were ‘at least a hundred’ memorials to her in England by 1921. A network of rest homes for nurses was set up in her memory, and the London Hospital – which bears Cavell’s blue plaque – named its new nurses’ home after her.

Overseas, statues went up in both Brussels and Paris and similar memorials in major cities of what was then the British Empire. A mountain in Canada and a bridge in New Zealand were named for her, too. Early filmed versions of Cavell’s life were Dawn (1928), starring Sybil Thorndike, and Nurse Edith Cavell (1939), starring Anna Neagle. A steady stream of biographies has since kept her name and story alive.