© National Portrait Gallery, London

Robert Clive was born into a gentry family from near Market Drayton in Shropshire. He was variously educated in Cheshire, London and Hertfordshire before accepting a clerkship with the East India Company, arriving in Madras in June 1744 after a long and arduous passage lasting 15 months. Having been notably aggressive as a boy, Clive was subject to fits of depression as a man. Finding himself friendless and isolated in India, he attempted suicide, but his pistol twice failed to fire.

Clive’s reputation as a military commander was established during his first two spells in India, either side of a sojourn in England. Untrained as a soldier, he entered into the East India Company’s military service after taking part in defensive action at Fort St David against the company’s French counterpart.

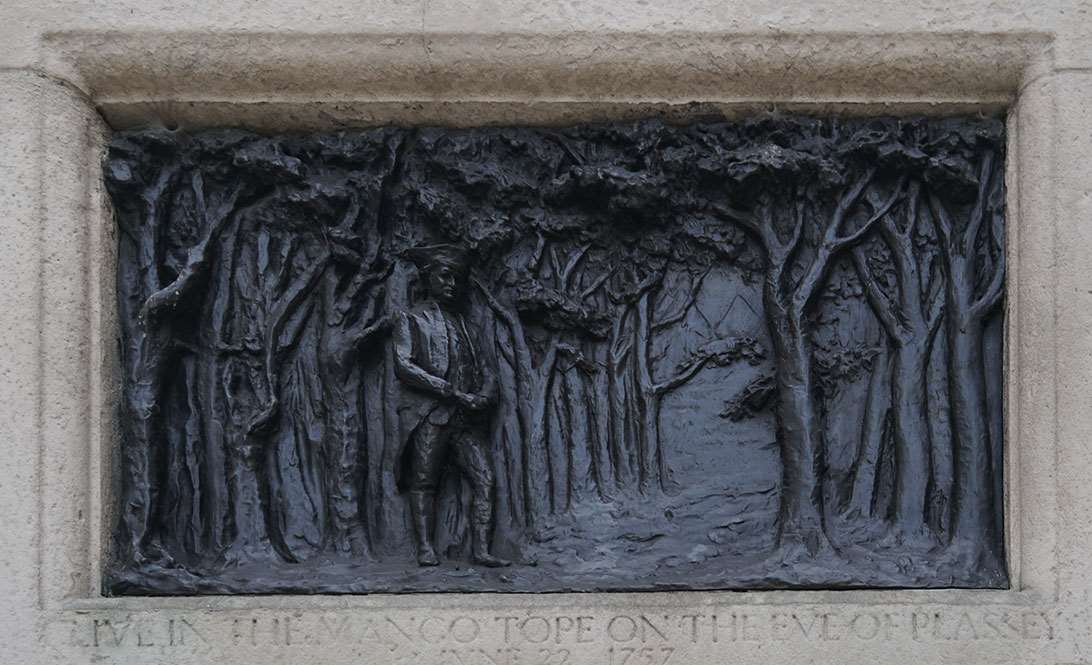

The key engagements that made his name were the siege of Arcot (1751) and the recapture of Calcutta thereafter, and the Battle of Plassey (1757), at which his army defeated French forces and those of the Mughal emperor’s viceroy, Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal. This was less a military triumph than one of organisation, duplicity – involving a fake treaty – and ‘divide and rule’ tactics: the defection of some of the Nawab’s officers was vital.

The victory at Plassey was cast as revenge for the ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’, a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, in which some British prisoners of the Nawab had died the previous year. Clive’s manoeuvrings, and subsequent engagements against the Dutch, left the East India Company in a position of sovereign supremacy in Bengal, and made him effective ruler of the region.

As early as 1759, Clive suggested to the leading politician Pitt the Elder that the Indian territories could be brought under the direct control of the British state. This did not happen for another century, but Clive has since been feted – and resented – as the originator of British rule over India.

He returned to England in 1760, and was made Baron Clive of Plassey (an Irish peerage) two years later. In 1764 he returned to Bengal with the title of governor and commander-in-chief, and consolidated the East India Company’s rule. He has been credited by some for introducing positive administrative reforms. However, the policies of the East India Company – in particular a punitive land tax – have also been blamed for causing or exacerbating a disastrous famine in 1770, which is reckoned to have killed ten million people.

By this time Clive was back in Britain, having amassed a huge personal fortune. Even in the 1740s he had showed his acquisitive nature by charging personal levies on all goods purchased by the East India Company’s army. In the aftermath of Plassey he received ‘presents’ worth £234,000, which has been described by one recent historian as ‘one of the largest corporate windfalls in history’. Clive’s fortune bought him a grand town house in Berkeley Square – now marked with a blue plaque – as well as estates in Surrey, Shropshire, Monmouthshire and Ireland.

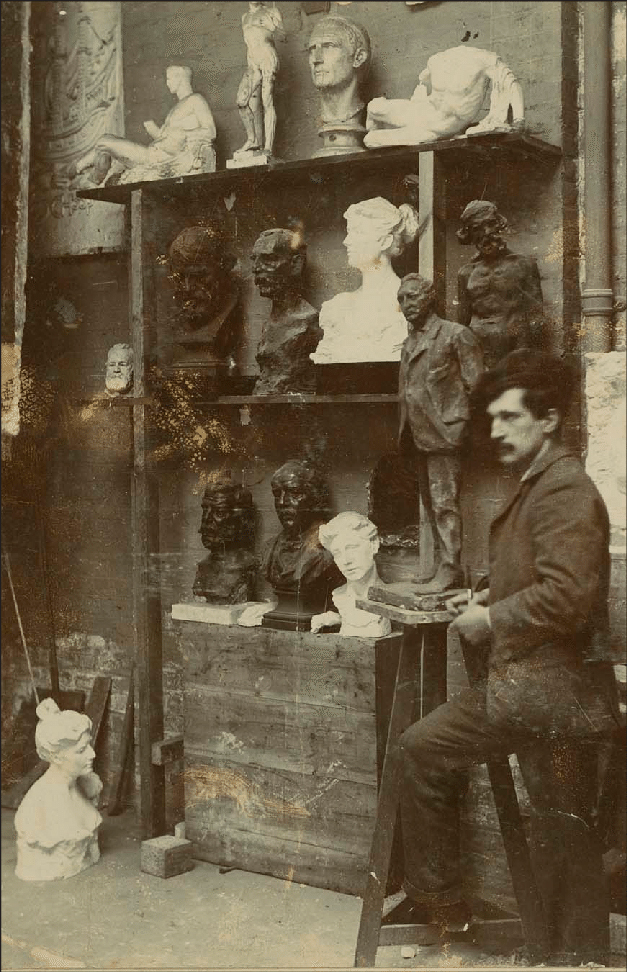

© Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images

Such conspicuous display of wealth excited a great deal of resentment, and newly rich ‘nabobs’ such as Clive were seen as interlopers upon traditional aristocratic privileges. Clive, who had acquired a seat in the House of Commons, became the subject of a parliamentary inquiry into corruption. He was defiant, telling its chair that given the opportunities he had for self-enrichment ‘I stand astonished at my own moderation’.

Clive was exonerated in 1773, but his fortune did not buy him health and happiness. He died the following year at his home in Berkeley Square in mysterious circumstances, and was buried in apparent haste at Moreton Say, Shropshire. It was widely believed that he took his own life, or that his illnesses led him to take an accidental overdose of opium, on which he had become reliant. A recent biography rates it as possible that he was murdered. At his death Clive was reckoned to be worth half a million pounds – a vast fortune by the standards of the day.

Clive did not enjoy a positive reputation at his death or in the years immediately afterwards. But after India came under the direct sway of the British Crown in 1857, his lionisation as a hero of empire began. A statue was raised to him in Shrewsbury in 1860; by Marochetti, it is similar in style to John Tweed’s later representation.

Over recent years views of Clive have tended towards the negative as the history of the British Empire has been subjected to more critical appraisal. The historian William Dalrymple has called him ‘a vicious asset-stripper’. Others have presented him more as a product of a corrupt system, and noted his personal bravery. His Oxford DNB entry concludes simply that ‘he was an architect of empire whose influence has cast a lengthy shadow over the history of Britain and India’. Of that there can be little doubt.