The Battle of Hastings, fought on 14 October 1066, is the most famous battle in English history. There is widespread consensus among historians that William the Conqueror founded Battle Abbey in penance for the blood shed at the battle and to commemorate his great victory, on the very spot where he defeated King Harold.

It has been suggested, however, that the battle was not fought here. Several alternative locations have been put forward, including Crowhurst, about three miles south of Battle, and Caldbec Hill, about a mile to the north. Advocates of both sites claim that the Battle Abbey monks invented the association between their abbey and the battlefield in the Chronicle of Battle Abbey, written in the late 12th century, 100 years or more after 1066.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE FOUNDATION OF BATTLE ABBEY

Monastic Invention?

The Chronicle provides a colourful account of the abbey’s foundation. It describes how, just before the battle, William vowed to found an abbey, and insisted that it should be sited on the battlefield, even though the local ground conditions were unfavourable. In fact, according to the Chronicle, the monks overseeing construction were so dismayed with the spot that they decided to build their monastery a little way off, before being ordered to move onto the correct spot by the king.

But there is perhaps good reason to question whether the monks’ account can be trusted. During the 12th century they were embroiled in a hard-fought legal battle with the Bishop of Chichester about his authority over the monastery. They argued that they enjoyed independence from his jurisdiction thanks to liberties granted to them by William I. To prove this they forged at least two charters purportedly issued by William.

So did they also invent the story about the abbey being located on the battlefield, to increase the prestige of their house?

A Long Pedigree

The answer is no, they did not. While some aspects of the story in the Chronicle, such as William’s vow before the battle, are probably later invention, the claim that the abbey was built on the site of the battle has a longer pedigree and is found in many other historical sources. The earliest is the collection of annals known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Although the Chronicle’s accounts of the battle are very brief, in one annal for 1086 there is an obituary of William I, written by a man who claimed to have known the king and to have been present at his court. It states:

On the very spot where God granted him the conquest of England he caused a great abbey to be built; and settled monks in it and richly endowed it.

Chroniclers and historians writing in the early 12th century told the same story. One of them, William of Malmesbury, wrote in his Deeds of the Kings of the English about 1125 that the abbey:

is called Battle Abbey because the principal church is to be seen on the very spot where, according to tradition, among the piled heaps of corpses Harold was found.

Other contemporary writers – including John of Worcester, Orderic Vitalis and Henry of Huntingdon – agree. And a life of William the Conqueror, written at Battle Abbey in the second decade of the 12th century, states that Harold and his army arrived ‘at a place now called Battle’ and that the battle took place ‘on the site where William, count of the Normans, afterwards king of the English, had an abbey built’.

So the notion that Battle Abbey was located on the site of the Battle of Hastings was not a much later invention – it was current by at least the second decade of the 12th century. The statement in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is hard to date for certain, but if it was written by a courtier of William I, then the association between abbey and battlefield was made within living memory of the battle. And the tradition that the east end of the abbey church was built on the spot where Harold’s body was found had its origins long before the Chronicle of Battle Abbey was written.

Viewed historically, then, there is good reason to be confident that Battle Abbey lies on the site of the Battle of Hastings. Further, none of the proposed alternative locations are identified as potential sites for the battle in the historical sources, and there is no evidence to suggest that anybody questioned the abbey’s claim in the years following the battle.

An Inconvenient Site for an Abbey

Circumstantial evidence is presented by the abbey’s location. Building the abbey on the side of a hill presented the monks with practical difficulties they could have avoided had they chosen to build elsewhere. It is difficult to see why they would have chosen to build the abbey in such an awkward spot without a compelling reason.

Image: The high south end of the east range of the abbey buildings reflects how difficult it was to provide a level floor for the dormitory on the first floor, because of the steep slope of the hillside on which King William insisted the abbey should be built

The Archaeology

Archaeology could, in theory, provide evidence which enhanced our understanding of the battle, if buried artefacts or deposits associated with it were uncovered. Strikingly, though, no archaeological artefacts associated with the battle have been found at the abbey. Does this undermine the abbey’s claim?

In part the absence of evidence is because there has been relatively little archaeological investigation at the abbey. But more significantly, the chances of material surviving from a single day in 1066, however fateful, is very low. This is partly because such evidence is likely to be of an ephemeral nature, and will have been destroyed by the clay that makes up the underlying geology of the site, and which is relatively acidic compared to other historical battlefields that have preserved buried features.

But more importantly, the very act of building the abbey and the subsequent centuries of occupation involved major changes to the topography of the ridge on which it sits, including terracing and levelling of the sloping ground to allow construction of buildings. According to the historical sources describing the battle, the top of the ridge was where Harold placed his standard and was the focus of much of the fighting. So the changes which occurred here after 1066 will have seriously eroded most, if not all, of the potential archaeological evidence that might be expected to survive from the 11th century.

We must hope that material from 1066 could have been buried by the later ground disturbance, and awaits discovery.

The Shape of the Battle

While the weight of the historical evidence suggests that Battle Abbey does indeed mark the very spot of William the Conqueror’s great victory, there remain some fundamental questions about the character of the battle. One of these is how it ranged across the landscape. While the top of the ridge and the site of the abbey’s church place an important marker on the battlefield, what was the shape of the fighting around it?

Almost all the traditional depictions of the battle present the fighting as occurring roughly on a north–south axis, with Harold’s army lined up to face directly south towards William’s forces. These reconstructions may have been coloured by the creation of parkland to the south of the abbey after 1066, leading to the assumption that the open sloping ground due south of the abbey preserved the land across which William’s army approached Harold’s. Landscape analysis undertaken in 2013, however, suggests that in 1066 this ground was bisected by streams and probably marshy, making it potentially difficult for William’s infantry to cross.

It seems more likely that William approached the battle from the south-east, along a ridge of high ground leading from Hastings. It is possible, therefore, that the main thrust of his attack came from this direction, and that Harold’s shield wall faced this way too. This would mean that the open land south and south-east of the abbey church now in the care of English Heritage would have been contested by the left flank of William’s army and the right flank of Harold’s. If so, much of the fighting would have taken place where the streets and houses of Battle town now stand, with its climax focused on the later site of the abbey church.

By Roy Porter

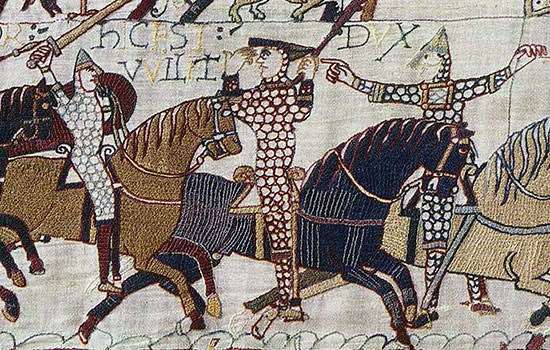

Top image: The scene from the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the death of King Harold of England at the Battle of Hastings (© GL Archive/Alamy)

Read More

-

What Happened at the Battle of Hastings

At dawn on Saturday 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Read what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

The Foundation of Battle Abbey

Battle Abbey was a memorial to William’s great victory – but it was also an act of penance. Find out how this great abbey owes its origins to the Battle of Hastings.

-

History of Battle Abbey and Battlefield

Read an in-depth history of Battle Abbey founded from its foundation to its suppression and beyond.

-

Description of Battle Abbey and Battlefield

Learn about the remains of the original Norman abbey and the many later monastic buildings that survive.