The Rise and Fall of a Tudor Wool Factory

How the Heydon family of Baconsthorpe Castle in Norfolk made a fortune from the East Anglian wool trade – and then lost it all.

THE RISE OF THE HEYDONS

During the Tudor period, the landscape around Baconsthorpe Castle was very different from the peaceful arable fields there today. At the height of the Heydon family’s prosperity, the castle was surrounded by pasture, grazed by many thousands of sheep.

John Heydon I, who died in 1480, had risen to prominence as a lawyer and the chief agent in East Anglia of William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk. He probably began his castle in the 1450s. From the start, he intended Baconsthorpe to provide his family with an impressive residence to show off to their neighbours.

But it was under the Tudors that the Heydons became even richer, not from practising law but thanks to their part in the lucrative wool trade which was then the basis of so much of England’s – and especially East Anglia’s – wealth. This was a Europe-wide business, and the Heydons were major players.

PROCESSING PLANT

By the mid-16th century the castle lay at the heart of a vast and profitable wool-producing estate. Sir Christopher Heydon I (1518/19–79) once entertained 30 head shepherds of his own flocks at Christmas dinner, which suggests that there were 20,000 to 30,000 sheep on his lands.

Sir John Heydon II (c.1470–1550) even transformed the east range of the castle into a ‘factory’ for processing the wool from his huge flocks. Large windows provided light for the spinners and weavers to work by. The fine cloth produced at Baconsthorpe was sold both in England and the Netherlands.

The ability to produce raw wool, and then process it into textiles on site, made the Heydons even more rich and powerful.

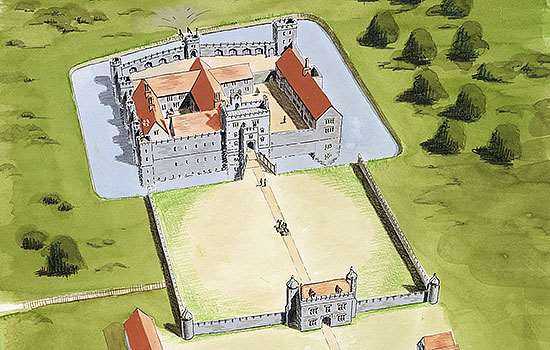

Their prosperity peaked in the 1560s, when Sir Christopher I had 80 servants, and ran his own coach with two horses – a rare and expensive luxury. Profits were spent on fine living and extensive building works. Sir Christopher built an elaborate outer gatehouse and created a large park, to which one of his successors added ornamental gardens and a lake.

BEYOND THEIR MEANS

Despite their wealth, though, there were already signs during Elizabeth I’s reign that the family were living beyond their means.

Although there was a decline in the wool and cloth trade at this time, the Heydon estates should still have been more than paying their way. But Sir Christopher I died in debt in 1579. He and his successors were not shrewd businessmen like the earlier Heydons, but lived as extravagantly as ever, throwing spectacular parties.

Sir William Heydon II tried to balance the books by selling land, but he too died in debt, in 1593. His eccentric son and successor, Sir Christopher II, preferred writing treatises on astrology to sheep farming. Finally, Sir John Heydon III, who plumped for the wrong side in the Civil War, gave up the struggle. He sold off all the Heydons’ Norfolk estates and, in about 1650, dismantled much of the castle to sell as building materials.

So, in barely 200 years, the Heydons had risen from proud beginnings to immense wealth before falling into ignominious decline.

By Katy Carter

Related content

-

Visit Baconsthorpe Castle

Visit the castle to explore the extensive remains of the Heydons’ impressive residence. Download the audio tour before you go.

-

History of Baconsthorpe Castle

Find out more about the castle’s history and how its development was inextricably linked to the fortunes of the Heydon family.

-

Description of Baconsthorpe Castle

Read a description of the extensive ruins of this moated and fortified manor house, which are a testament to the rise and fall of the Heydons.