Design and date

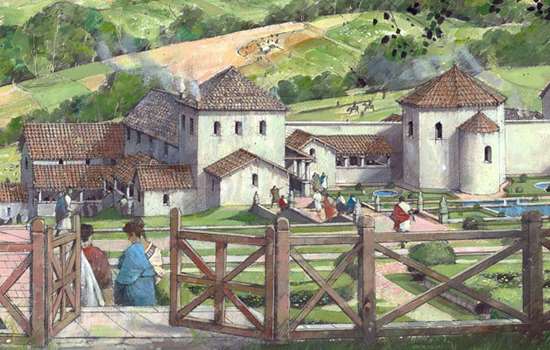

The villa at Beadlam had about 30 rooms, which were spread across three ranges built around a large courtyard. The northern range – the only one visible today – is a typical Romano-British winged-corridor house. This house comprised communal rooms in the centre and two private suites of well-appointed rooms on either side, connected by a long veranda.

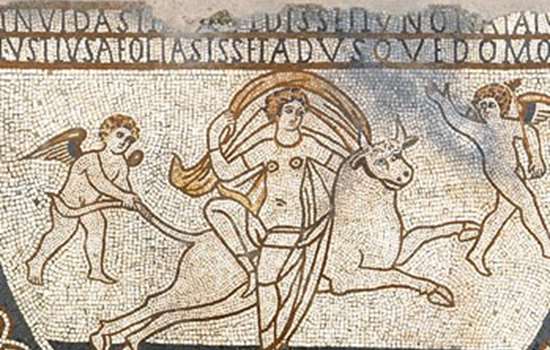

The western suite included a room with a heating system (hypocaust) and in the east suite there was an elaborate reception room with a fine mosaic. It may be that these suites were self-contained and belonged to different households, who shared the use of the other rooms.

A similar house lay just west of the courtyard and may have been occupied by another household. On the eastern side were further buildings that seem to have been used for industrial or agricultural processes.

The villa complex was probably constructed in about AD 300 and was occupied until about AD 400, just before the end of Roman Britain.

The 4th century AD was a time when elite Romans in Britain were spending their money on private villas, and comparatively few villas were built before this. However, at Beadlam an enclosure ditch and walled compounds for livestock pre-dated the villa, suggesting the site was in use earlier. It was quite common in Yorkshire and across Roman Britain for Iron Age farmsteads to be developed with a Roman-style building.

Who owned Beadlam?

During the conquest of Britain, the Romans seized land belonging to the many pre-existing British kingdoms. They created regions (civitates) to be governed by newly built large towns. In many cases elite families from the British kingdoms retained their status, but were expected to obey Roman laws, pay taxes to Rome and live like Romans.

Beadlam lies within a region formerly controlled by the kingdom of the Brigantes. After the Roman conquest, the region was administered from the newly built Roman town of Isurium Brigantum (now Aldborough). Evidence of occupation at Beadlam before the construction of the villa suggests that its owners were members of existing elites who had now adopted a Roman lifestyle. Other possible owners could have been retired soldiers who had been rewarded with land for their service, absentee landowners living elsewhere in the empire, or even the Roman emperor himself, who owned various estates in the province of Britannia.

Roman villas in Britain

For the Romans, a villa was a rural house owned by somebody of high social status. In the rich Roman provinces around the Mediterranean, such as Italy, villas of tens or even hundreds of rooms sat at the centre of large country estates.

In Britain, villas of such size and scale were rare. Of the 2,000 or so Roman villas that have been discovered, many contained only around a dozen rooms and were often similar to Beadlam in size. But they still demonstrate that Roman architecture had been adopted.

The purpose of villas was similar across the empire: they were designed not just for comfortable living, but to demonstrate the status of their owners. The western house at Beadlam, for example, featured a small bath-house, while the northern house had well-appointed reception spaces with central heating, wall-paintings and even a mosaic. Whoever owned Beadlam clearly wanted to show off their wealth to visitors.

Read more about Roman villasBeadlam and the wider landscape

Beadlam probably sat at the centre of a working estate that provided its owners with an income. Comparable estates show evidence for arable farming and pasture, the management of woodlands, quarrying and various industrial activities. Many of the buildings at Beadlam show evidence of metalworking. Since most of the population of Roman Britain lived in the countryside, it is likely that sites like Beadlam would have played an important part of the rural economy and had goods to trade with larger settlements such as Malton or Aldborough.

Compared to the south of Roman Britain, the north was largely dominated by the Roman army – most notably the many forts along Hadrian’s Wall – and evidence of elaborate civilian buildings like Beadlam is quite rare. However, Beadlam is one of a cluster of potential villa sites in the Vale of Pickering around Malton, which include Langton, Oulston and Hovingham. Excavations at each of them have revealed a rich array of Roman objects, including jewellery, pottery and expensive glassware, showing that such luxury items were in high demand even at the farthest extent of the empire.

Discovery and excavation

The site was known about in 19th and early 20th centuries but dismissed as ‘old cart sheds’. The villa remained undiscovered until the field was ploughed in the 1960s, when Roman finds were recognised among the surface material collected. Excavations in the 1960s and 1970s revealed the three ranges of buildings and uncovered a rich collection of domestic objects that reflect the site’s importance as a country residence in the 4th century AD. Although all three ranges were excavated, two were covered over and the northern house, which was the best-preserved, was consolidated and left visible.

The finds from the excavations, including the mosaic, are kept in the English Heritage archaeology store in Helmsley. You can view some of them in the gallery below.

Collection Highlights

The objects excavated at Beadlam are a time capsule of the site on its abandonment. The collection includes a nationally important assemblage of Roman glass, domestic ceramics, two hoards of iron objects, and other items associated with industry and trade.

Related content

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

-

Explore Roman Britain

Learn more about Roman daily life, politics, religion, art and commerce in this introduction to Roman Britain.

-

Hadrian’s Wall: History and Stories

Discover the histories, stories and mysteries associated with English Heritage’s Hadrian’s Wall sites.

-

History of Aldborough Roman Town

Find out more about the history of Aldborough and how it developed from an early settlement into a large bustling Roman town.

-

History of Lullingstone Roman Villa

Discover the history of this villa, which reached the peak of luxury in the mid-4th century when its spectacular mosaics were laid.

-

More Histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.