Mary

Mary was born in 1879 the daughter of Admiral Samuel Long and Mrs Long of Horndean in Hampshire. In 1905, she married a naval officer, Lt Hugh Jeffrey Middleton, the son of Sir Arthur Middleton, the 7th Baronet of Belsay Hall in Northumberland. They had four children together.

Mary’s life was changed at the start of the First World War when Hugh, who had retired from the Navy in 1909, was called back into service and tragically died upon his ship. After Hugh’s death, Mary lived at Belsay with her children, where they remained for the next 20 years.

For centuries, local service and politics had been the duties of the Baronets of Belsay. Sir Arthur Middleton had served as the MP for the City of Durham, and his grandfather Sir Charles Monck was a notable MP for Northumberland. Mary’s husband would have been expected to continue the tradition and so in his absence she took his vacant place on the district council in 1916. At the time, women only qualified for local office under certain conditions, in this case Mary’s status as a widow.

Alongside her burgeoning political career, Mary was on Northumberland’s Education Committee, President of the Northumberland Federation of Women's Institutes and chair of their executive committee and County Commissioner for Girl Guides. In her successful 1922 campaign for the Northumberland County Council she cited her local patronage and public service as evidence of suitability for the role.

Wartime Service

Mary’s local service was quite typical of aspiring woman politicians of the early 1920s, but the war opened new avenues for women to excel and lead, in areas traditionally barred to them.

In 1916 she was a warden in the Northumberland Guild of War Agricultural Workers, one of many ad hoc organisations formed to tackle the shortage of farm labour while men were fighting on the front. Mary ran a network placing, training and overseeing women working on farms across the county – labour vital to sustaining the war effort.

An article in Country Life described Mary as ‘a spirited worker and good organiser’, and when in 1917 the Ministry of Agriculture took formal charge of the provision of agricultural labour, Mary was appointed Organising Secretary for the Northumberland Board of Agriculture. The board was challenged to train women in merely a month to take farm jobs and then find them roles.

By 1918, she held the position of Honorary Secretary of the Northumberland Woman's County Agricultural Committee and was so highly regarded that when a similar scheme was developed in Scotland, she was sent to provide expert advice to the founding committee. She was later appointed to the Council of Agriculture for England and received the OBE for her service.

The First Female MPs

On 21 November 1918 the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act was passed, enabling all women over the age of 21 to stand for Parliament. Women over the age of 30 and who met a property qualification had been granted the right to vote earlier that year.

But even with these rights, the road to becoming an MP was far from easy. Women were largely selected for unwinnable seats and often at the last minute when no suitable male candidate could be found. This meant they had little time to establish themselves in the local community and ‘nurse’ the constituency, whereby candidates would attend community events and make donations to local causes in between elections.

Of the 17 women who stood in 1918, only Constance Markievicz from the Irish nationalist party, Sinn Fein, won her campaign. But she refused to swear the oath of allegiance to the British Crown and never took her seat in the House of Commons. Soon after, in 1919, the Conservative Nancy Astor won a Plymouth Sutton by-election and became the first woman MP to take her seat. She was later joined by the Liberal Margaret Wintringham, who was elected as MP for Louth in a 1921 by-election.

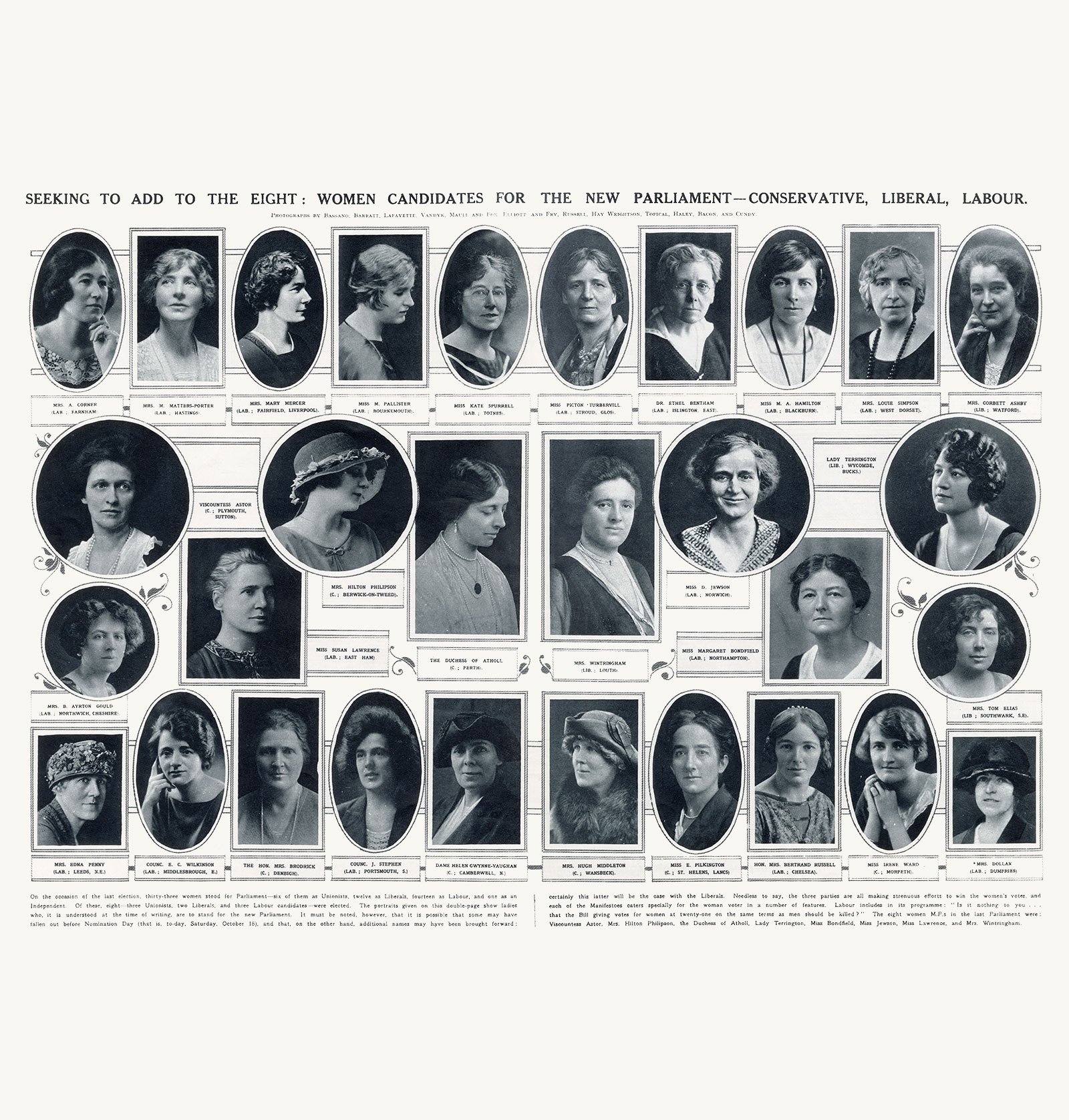

Despite 33 women standing in the 1922 General Election, only two – Astor and Wintringham – were successful. The Conservative Mabel Philipson won a 1923 by-election in Berwick-upon-Tweed. All three women were elected in seats previously held by their husbands, showing the importance of family connections in politics. The number of women candidates increased to 34 in the 1923 General Election, and 8 women were elected to Parliament from across the political spectrum.

A Hopeless Seat

Mary was one of 41 women candidates who stood for Parliament in the 1924 General Election. This was the largest cohort since women were granted the right to stand in 1918, but still a mere fraction of the over 600 MPs that were elected. The Labour Party paved the way with 23 women candidates, compared to 12 Conservative women and 6 Liberal women.

The candidates included suffragists and suffragettes, local politicians like Mary, trade unionists, and party activists. Many worked in the professions and were university educated, although the number of working-class women remained low. They also stood in a range of constituencies across the country.

Mary’s prospective seat was Wansbeck Northumberland – a rural area that also had large mining communities. Mary, a Conservative, was going up against the Labour Party’s George Warne, who had worked as a miner since the age of 12. He had defeated Mary’s predecessor by a margin of 4,452 in the 1923 election, and in 1924 Wansbeck was considered one of the safest Labour seats in the country. Mary’s chances were therefore somewhat hopeless from the start. Even the chair of the Wansbeck Unionist Association admitted that Mary was ‘a very brave woman’ for standing.

On Campaign

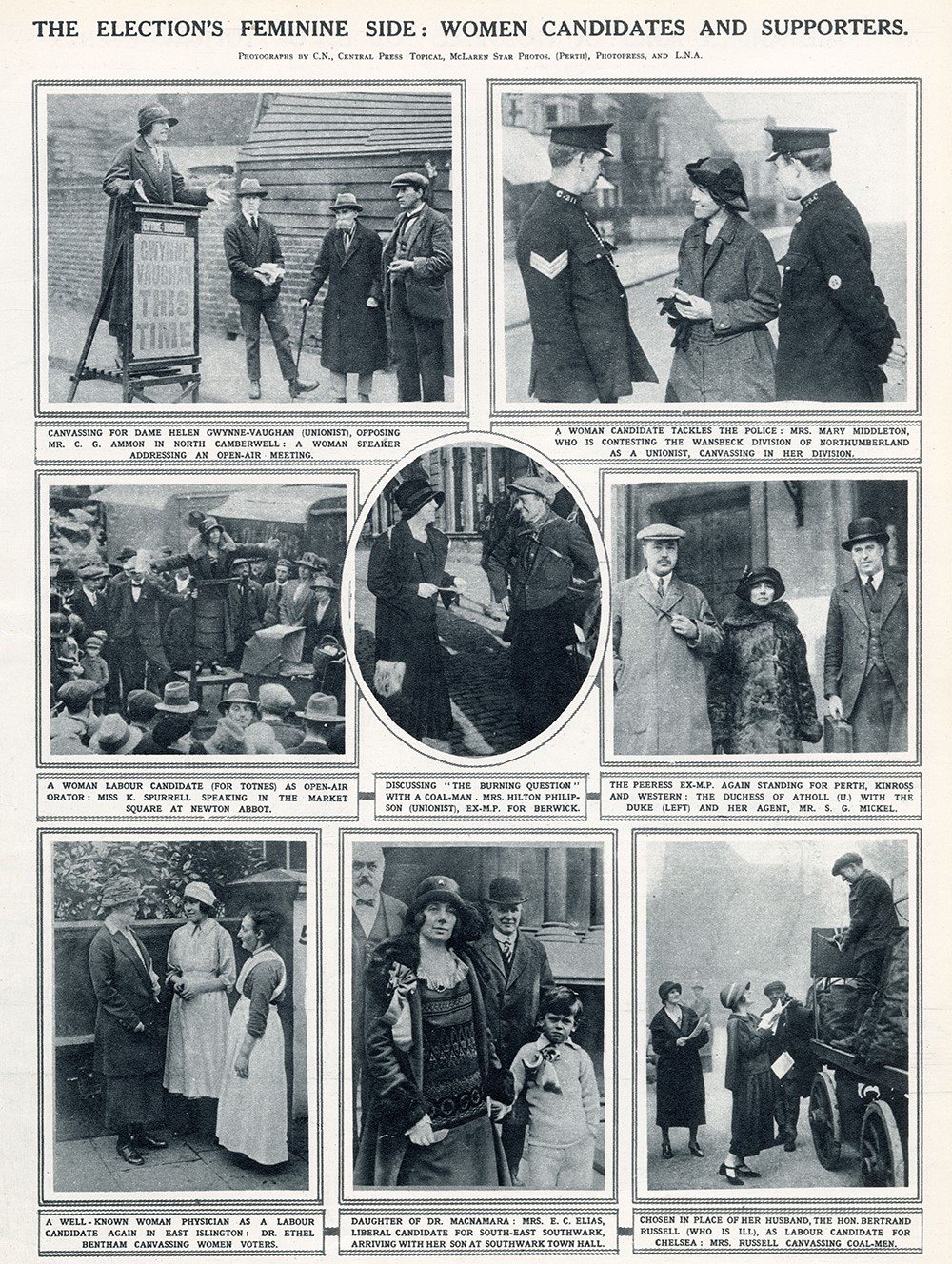

Election campaigns were largely conducted through public meetings, which was an advantage for candidates like Mary – she had a wealth of public speaking experience and gave speeches at party events and fundraisers. As a local dignitary she opened schools and presided over community events, such as flower shows or sporting competitions. Mary’s speeches were widely reported, and she was favourably described as a ‘racy’ speaker.

Mary’s campaign was expected to follow her party’s national manifesto. In 1924, the Conservatives criticised Labour for failing to keep its election promises on issues such as unemployment and housing, and their controversial decision to sign a trade treaty with the Soviet Union. Mary’s platform included her opposition to the Soviet Treaty and she argued that the Conservatives would be able to deal with unemployment by finding new markets in the Empire not Russia.

There was also an expectation that women candidates should focus on traditional female concerns such as those related to children and social reform. Mary tried to appeal to female voters directly by advocating for more women in Parliament to help with social reform. Just five days before polling day, she campaigned for women to vote for her regardless of their political affiliation, since ‘women had never had such a chance as they had this election, and she was relying on them to help her win’.

A narrow loss

As expected, Mary did not win the Wansbeck seat in 1924. But she greatly increased the Conservatives’ share of the vote – a knock to Labour’s confidence in what was supposed to be an easy seat. When visiting the House of Commons and bumping into the Labour MP George Warne (who had defeated her), she recounted: ‘I think he thought I was a ghost come to turn him out.’

The Conservatives celebrated the achievement and she was immediately adopted as the presumptive candidate for the next election.

Mary continued to be the official prospective candidate for Wansbeck, but in January 1927 she withdrew. A newspaper reported her opinion that she considered ‘singing and music to be more worthwhile than politics’, but that the reason for her retirement was otherwise unknown.

Yet in 1929, she was expected to run as an Independent candidate for the Wansbeck by-election and there was anticipation that the Conservative vote would be split. She said that she believed the official Conservative candidate, Mr Moffat-Pender, had no chance of success. In the end, Mary stood down from the running and Moffatt-Pender was trounced by the Labour candidate, GW Shield, by over 10,000 votes.

Despite briefly attempting to return in the late 1930s, when she was denied in favour of a candidate who was a ‘man’s man’, Mary never again stood for office. She died in 1949.

Legacy and Politics in the North East

Mary Middleton was not the only woman to stand in the North East of England in 1924. Irene Ward contested Morpeth for the Conservatives, Mabel Philipson stood as the Conservative candidate for Berwick-upon-Tweed, and Ellen Wilkinson was adopted as the Labour candidate for Middlesbrough East. Wilkinson was elected in 1924 and Ward went on to win in 1931, serving for 38 years.

The number of women MPs increased from 4 in 1924, to 14 in 1929, and 15 in 1931. Margaret Bondfield was also appointed Minister of Labour in 1929, becoming the first female Cabinet Minister. When questioning why so few women were elected, the press seemed to ignore the fact that women were largely selected for ‘hopeless’ seats.

Despite the small number of women MPs in the interwar years, their increasing presence as candidates was vital in improving women’s visibility in electoral politics and presenting female political voices to a national audience. No longer could it be said that women were too weak or fragile to stand for Parliament and sit in the House of Commons.

The small number of women MPs also played a significant role in championing legislation that would have a positive impact on the lives of women. This included the 1928 Equal Franchise Act, which would finally allow women to vote from the age of 21 – on the same terms as men.

By Andrew Roberts and Lisa Berry-Waite

Header image: Mary Middleton pictured with policemen while campaigning in Wansbeck, October 1924. © Illustrated London News Ltd. / Mary Evans

Explore More

-

Women who made History

Read about the remarkable lives of some of the women who have left their mark on society and shaped our way of life.

-

Pioneering women in London

Take a look at some of the figures in London’s history commemorated by blue plaques who fought to open up new opportunities for women.

-

History of Belsay

Read the history of the Belsay estate from its medieval castle to its 19th-century hall.

-

Episode 289 - Women in politics in the 1920s

Listen to our podcast episode on Mary Middleton and women in politics in the 1920s.