The political context

The crowns of England and Scotland were united in 1605 but full political union between their parliaments only occurred in 1706 and 1707, by two Acts of Union. From that time, the two countries were governed as one and, together with Ireland, formed Great Britain. English and Scots voted for the union, but it was not universally popular in Scotland, despite the potential economic benefits.

Jacobite sympathies in Scotland and England resulted in the rising of 1715, which aimed to place James II’s son, also James Stuart (later known as the Old Pretender), on the throne. Although the Jacobite army took over a large part of Scotland, they achieved only stalemate at the Battle of Sheriffmuir (8 miles north of Stirling, in Scotland) on 13 November. The following day another Jacobite force surrendered to British government troops at Preston in England.

The bloodshed and near success of the 1715 rising, the presence of Jacobite sympathisers in England, and the easy penetration of hostile forces as far as Preston, stirred the British government to prepare for more trouble. In the Scottish Highlands, though several barracks already existed, more were built as part of a wider counter-insurgency strategy. It also resulted in the new barracks at Berwick. Berwick’s strategic position, near the England–Scotland border and close to the main eastern road linking the two countries, meant that it had always been an important garrison town.

The Jacobite cause

In 1688 the Catholic king of England, Scotland and Ireland, James II (James Stuart; reigned 1685–8) was deposed and replaced as monarch by the protestant William of Orange (William III; r.1689–1702). Although the coup enjoyed majority support, there remained a minority that supported the Stuarts, and a political undercurrent for their restoration lived on. When it was politically advantageous, the Stuart cause was given support by France, Spain and the Pope, resulting in several attempts to place James and his descendants on the throne.

The supporters of the Stuart cause came to be known as Jacobites. They organised several uprisings, the most serious of which were in 1689, 1715 (known as the ’15), 1719 and 1745 (the ’45). The Jacobites’ defeat at Culloden in 1746 effectively put an end to their cause as a serious political threat.

Image: Portrait of James Francis Edward Stuart (1688–1766), nicknamed the Old Pretender, c.1720 (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

The nature of barracks

Today, soldiers live in barracks that are purpose-built, secure accommodation, usually separated from the civilian population. In early 18th-century Britain, however, barracks were rare. People had been wary of large concentrations of soldiers since the Civil Wars of the mid-17th century, when armed forces had often terrorised and oppressed civilian communities. In consequence, it had become normal for a regiment of soldiers to be dispersed over a wide area, housed in taverns and livery stables.

However, dispersal was a strategic disadvantage in the event of real danger, when time was wasted assembling a regiment to fight as one force against the enemy. In the aftermath of the ’15, the British government decided that the need for barracks to hold a concentrated force at Berwick-upon-Tweed overrode the usual sensitivities.

Design and building

The barracks were built by the Board of Ordnance, the government body responsible for constructing barracks and fortifications and for supplying the armed forces with weapons, ammunition and equipment. Initially, in 1717, the famous architect Sir Nicholas Hawksmoor (c.1662–1736) was asked to prepare a design.

It is likely that the baroque flamboyance of his drawing did not square with the Board’s purse, or that they feared such a showy design might not go down well given civilian dislike of barracks. Instead, a plainer design was developed from Hawksmoor’s original. The Board kept the core but ditched most of the decorative detail, resulting in a sombre, if imposing, appearance.

That same year, the approved site on the edge of Berwick-upon-Tweed was surveyed and secured. It lay within the town walls but in an open, undeveloped area called Ravensdowne. Contracts were quickly made with suppliers of raw materials and with builders. One of the Board’s military engineers, Captain Thomas Phillips, supervised the project, aided by the Ordnance storekeeper at Berwick, John Sibbitt, together with several works’ overseers. The main phase of building was completed in 1721.

The plan of the barracks

The barracks, built to accommodate 600 men and 36 officers, are arranged in four ranges around the barracks ‘square’. The grandest element, a stone arched entrance, bears the coat of arms of King George I. It was originally flanked by simple screen walls that closed off the square; today’s single-storey buildings, a guardhouse and an officers’ mess, are 19th-century additions.

The longer sides of the square are framed by the three-storey accommodation ranges facing each other, with the fourth side taken up by the Clock Block. The latter was built in 1739–41 to replace the original Ordnance Storehouse, which had proved to be too small. On the outer sides of all three ranges were walled compounds for support buildings, including latrines, and an outside storage area for the Ordnance storekeeper.

The two accommodation ranges were for both officers and other ranks. Their original stone faces were screeded in concrete in the 19th century, making them even more severe. Each range has a double plan with an M-shaped roof and is subdivided into ‘blocks’ by four staircases that serve all floors. In each range, three staircases serve four soldiers’ rooms on each floor, 72 in all. Each room was plain, with a window and a fireplace. There were no latrines or washing facilities inside.

The fourth stair in each range, nearest to the entrance, served an officers’ block. In Hawksmoor’s design, the officers’ blocks comprised separate but linked pavilions, but as built, they were distinguished from the soldiers’ blocks only by windows with arched heads, rather than flat ones. Officers had comfortable accommodation and could often expect individual rooms.

Life in the barracks

Ordinary soldiers were from the unskilled poor in society and their life was hard. Though the barracks were rarely full, there were often a few hundred soldiers living in them. Conditions were cramped and insanitary. Eight lived in each room, with two sleeping in each wooden bed. Between the beds, a table and benches formed the dining and working table. One fireplace provided for warmth and cooking, though coal was often rationed.

There were no indoor toilets; at night everyone used a wooden tub that was emptied in the morning. The odour from sweat, tallow (animal fat) candles, pipe smoke and food would have made the rooms pungent, even by the standards of the day. There was no privacy, even for those few soldiers who were permitted to marry and brought their wives and children to live with them.

Regular soldiers spent a lot of time in repetitive drill, much of it on the barrack square. This was designed to instil mastery in the use of their personal weapons, and discipline in collective manoeuvres and weapons drill, so that these skills would be instinctive in real fighting. Soldiers also took their turn at guard duty, watch, anti-smuggling patrols and policing activities in support of the area’s civil authorities.

Image: Reconstruction of a barrack room as it would have looked in 1757

Later history

After the Jacobite rising in 1745, the sources of unrest, particularly in the Highlands, were gradually subdued by repression, depopulation – turning people out of their homes and lands (the Highland clearances) – and breaking up the Scottish clan structures. All this was achieved by more soldiers in defensible barracks and forts, linked by new roads that cut across the wild highland landscape. This proved to be the end of the Jacobite cause. As Scotland became more peaceful, Berwick-upon-Tweed’s strategic importance declined.

Nevertheless, soldiers remained in the barracks throughout the 18th century, though in smaller numbers and often including Invalid Companies, formed of older men or others unfit for service abroad. During the Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815) the garrison was formed by reserve forces of militia and volunteers, freeing regular troops for service abroad. The militia was raised by a ballot of adult men, to serve only in wartime; volunteers served of their own will.

After 1815, a lasting peace meant that the barracks were neglected and sometimes unoccupied. From the 1850s they were reoccupied intermittently, as fear of a resurgent France grew again.

Between 1868 and 1881, successive Secretaries of State for War Edward Cardwell and Hugh Childers reorganised the Army in a series of reforms. One key reform established a regional structure based upon county boundaries, within which each regiment (now named, rather than numbered as they had been before) had a permanent home depot. In 1881 Berwick-upon-Tweed Barracks became the permanent home depot of the King’s Own Borderers (King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) from 1887).

Alterations to the barracks thereafter provided better accommodation, sanitary and recreational facilities. In 1939, there were 250 men at Berwick-upon-Tweed Barracks, four to each room, with married quarters, showers and baths, cookhouses, dining halls, a gymnasium (built in 1901) and a Regimental Institute (in the Clock Block) for leisure and entertainment. Concern for the ordinary soldier had come a long way since 1721.

The barracks continued as the home depot of the KOSB until November 1963.

By Paul Pattison

Find out more

-

Visit the Barracks

Discover England’s first purpose-built barracks for yourself, and find out more about military life and work in this border town.

-

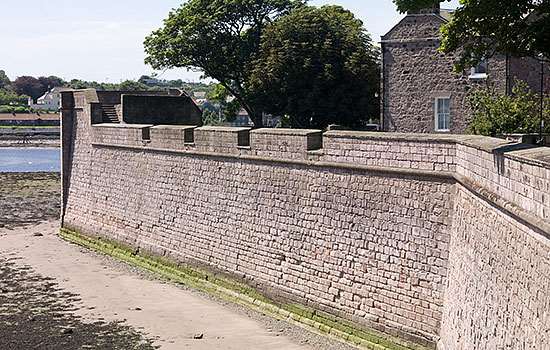

History of Berwick Castle and Ramparts

Berwick-upon-Tweed’s massive walls are a powerful reminder of the turbulent history of the Anglo-Scottish borders.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook includes a full tour and history of the barracks and the town’s fortifications, with plans, maps and historical images.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.