Early Life

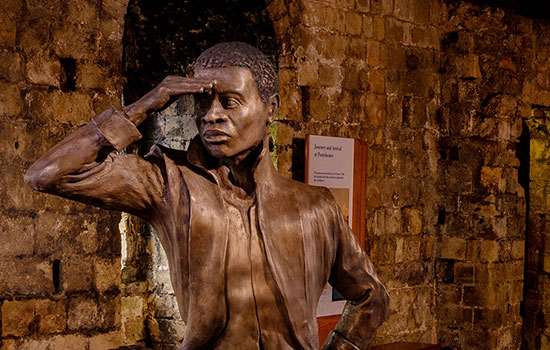

Arthur Roberts was born in Bristol in April 1897 to a West Indian father, David, and English mother, Laura. The family moved to Glasgow where he was brought up in the cramped tenements of the Anderston district just west of the city centre. We know little of his early life or family members. At night he slept in a hotel near to the family accommodation, returning home during the day for meals.

Arthur seems to have done well at school, staying on beyond the leaving age of 14. Certainly his war memoir conveys an intelligent, eloquent young man, well read and with broad interests, who was also a musician and artist.

A New Recruit

By his own admission Arthur was ‘possessed of great military inclinations. Anything in the form of drill, or manoeuvres, interested me exceedingly.’ In February 1917, aged 20, he enlisted with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) regiment before transferring to the Royal Scots Fusiliers in June of that year.

After a short period of basic training in Scotland, Arthur was shipped to France in May 1917. His diary records exhausting days of drill and bayonet practice at the base camp in Étaples, commonly known as the ‘Bullring’, interspersed with trips to the cinema and into the local town.

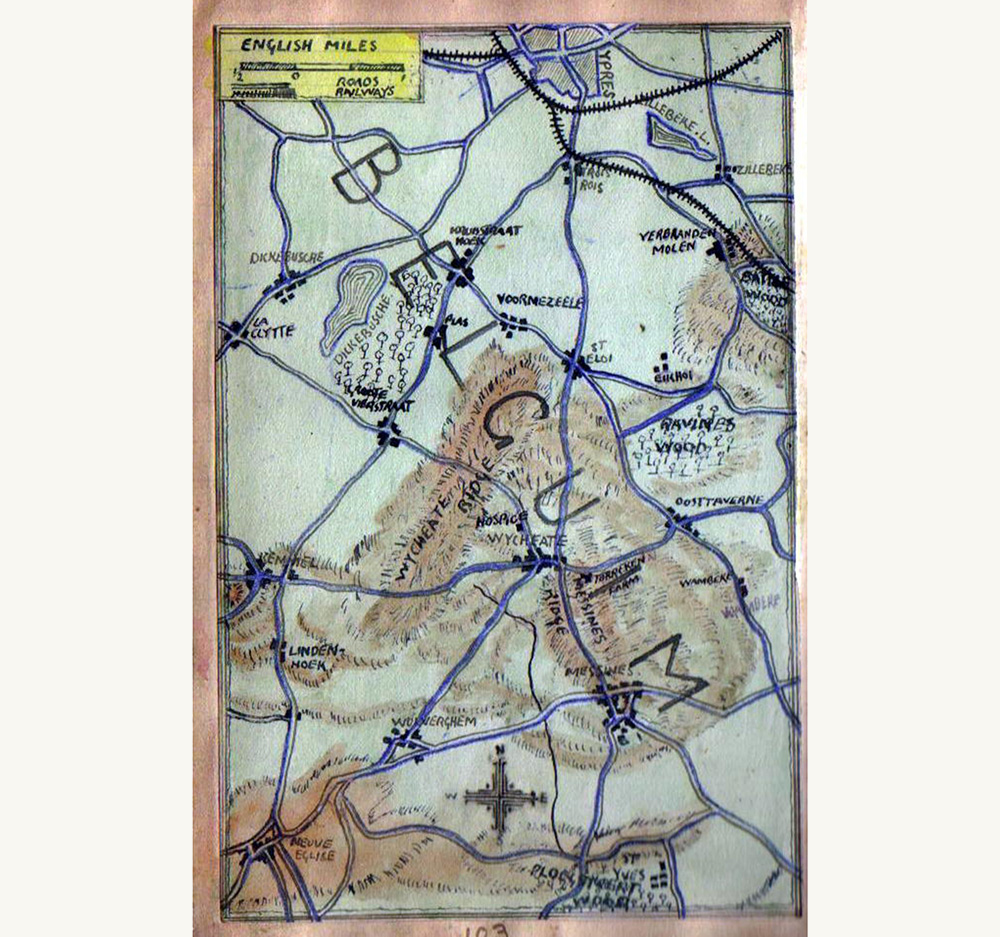

On 3 June his draft was ordered to move to the front at Ypres as part of a co-ordinated attack at Messines Ridge, just south of the town. Arriving on the 5th, Arthur’s diary reports several easy days followed by an exhausting march to the second line trenches. Once there he admits to being unprepared for the reality of the experience yet to come. Looking out across no-man’s land for the first time he was almost disappointed recalling that, in his ignorance, ‘guns and shells were only but sounds to me’. Where, he asks, were the horrors of war the people at home ‘were making such a fuss about’?

On the Front Line

Five days later Arthur’s war changed. On the 14 June the German bombardment all but destroyed the trenches around him. Moving his way through the cratered lines he came across his first dead soldier, a sight, he later wrote –

that is practically photographed on my brain. At that sight, it was as if my ruminations had been cast from their exalted altitude of self-contentedness, to an abyss of nauseating realities…the poor corpse lay like a rag doll with all the stuffing knocked out of it, and just flung down as if in anger or haste.

Over the following four months Arthur was at the front line three more times, at Pilckem Ridge, Neuve-Église and finally Kemmel. His diary records the exhausting swings in emotion suffered by men in his situation. On 20 September he reports, ‘Business is slack around this quarter. It suits us fine’. The next day, after a harrowing night as a ration guide to forward positions, Arthur bluntly notes, ‘I nearly won a wooden cross on my back’.

On 1 November Arthur was granted a permanent role at base due to a prolonged injury to his foot.

Black Soldiers on the Western Front

From the outset of hostilities in Europe the role of black men in Britain’s military was strongly contested within the government and military authorities. At best attitudes could be uncertain; at worst they were openly prejudiced. The Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener wrote at the time: ‘Blacks’ colour makes them too conspicuous in the field…Black soldiers [are] a greater source of danger to friends than enemy’.

Active discouragement of West Indian men joining the army begrudgingly gave way in 1915 with the formation of the British West Indian Regiment (BWIR). Most BWIR men were deployed across the Empire. Those few who were sent to France experienced segregation and a service experience little different from that of a labour battalion.

The place of black British men in the military was more confused, and Arthur’s ability to enlist may simply have come down to the personal whim of the recruiting officer. Once he arrived in France, Arthur might have expected to face barriers to active service on the front line, and discrimination from his fellow soldiers.

Arthur’s Account

Arthur makes no reference to his colour in his writings of his wartime experience. He offers no sense of any mistreatment, any lack of respect, singling out or other prejudice on any level – whether as a matter of colour or other aspects of his character.

His account is not without its pointed comments, expressed in a wry humour about the officer class, injustice and the system. In one instance he comments on the hierarchy of rail transport:

There are two trains in, a coach train, and a truck train. Instinctively, Tommy gazes on the trucks […] the carriages are for his superiors. Perhaps the insinuation is rather marked, but if the rank and file received the cattle’s portion then the fact is obvious.

At the outset Roberts tells us that he intends to be frank and is writing a book of facts. But this is not a book about others. Throughout Arthur barely mentions anyone else by name, even members of his family. What others thought, how they acted and their impact on Arthur is missing from the diary and the longer narrative.

Though Arthur seems pleased to be one of the chaps, there is little sense of camaraderie or close friendships expressed in his writings. His leisure time, often at the cinema or a musical revue, seems to have been spent on his own. His concerns in his writing are around his own actions, emotions and personal journey. If Arthur did suffer prejudice it has been omitted from his account, but so too have many other aspects of his service that would also have affected him. We therefore cannot know the whole truth of his experience.

KOSB and Berwick Barracks

After the war Arthur returned to Glasgow, secured an apprenticeship and a successful career as an engineer and then as an electrician. He married Jessie Finnigan in 1956, with whom he had lived for over 20 years. Jessie died a year later. Arthur himself entered a care home on 1979, dying in January 1982.

Arthur Roberts was a patriot. He enlisted to fight for the king, the country and empire without question or cynicism. Those near three years in service, as for so many, were a defining point in his life. The King’s Own Scottish Borderers, his first regiment, will have held a special place across his life. The KOSB was based in the 18th-century Berwick Barracks in Northumberland since 1881, and Arthur would have felt a strong affiliation with the barracks as the emotional and administrative heart of his regiment. He was one of theirs, and in that way, Berwick was in some ways his home.

I wondered if I was in the thoughts of somebody at that precise moment. Then came a wave of pride. Here was I among men sharing the risks and uncertainties of being in the very front ranks of the empire, against its enemies. My patriotism was strong in my breast then, and as a youth will do I began to dream of what might be. Would a great chance come my way, if so, would I make the best of it. Of course I would, I am a man now, a real man.

Then the tiny grim imp of stern reality slowly inserted his prong of cold reason, and like a flash I saw again our front line and its occupants. Perhaps they too had dreamed, but reality had shattered their castles. Oh my God! Would the supports who would follow in our tracks find me mangled and torn, gazing into the great beyond. Ugh! The thoughts sent the cold sweat from my brow. Oh this waiting is worse than a hundred deaths. Heavens, will the order never come?

From the memoir of Arthur Roberts, reflecting on the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, 31 July, 1917

Further Reading

This text has largely been constructed using the transcriptions of Arthur Roberts’ diary and memoir in As Good as Any Man.

M Miller, R Laycock, J Sadler, R Seriville, As Good as Any Man (Stroud, 2014)

D Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History (London, 2016)

M Sherwood, ‘As Good as Any Man: Scotland's Black Tommy’, The Black Presence in Britain, 8 November 2014 (accessed 9 April 2021)

Recognize Black Heritage & Culture and the University of Birmingham, Stories of Omission: Conflict and the Experience of Black Soldiers, 2018 (accessed 9 April 2021)

Explore More

-

Black history

Black history is a key part of England’s story, and helps us to reflect on the connections between the past and present.

-

History of Berwick Barracks

The barracks at Berwick-upon-Tweed are the largest and finest barracks built in England in the early 18th century.

-

Painting our past

We've commissioned a series of six portraits celebrating the lives of people of the African diaspora whose stories have contributed to England’s rich history.