The Abbey’s Foundation

The years around 1100 were a time of great religious fervour, manifested in the foundation of several new, reforming monastic orders. One of these grew out of the abbey of Savigny in Normandy. Its pious, grey-clad monks soon attracted the support of the Anglo-Norman elites who ruled England, including Roger de Clinton, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. On 8 August 1135 Roger issued a charter formally founding Buildwas Abbey. The first abbot was called Ingenulf and the monastery was dedicated to the Virgin Mary and St Chad, a 7th-century bishop whose relics were enshrined at Lichfield Cathedral.

King Stephen (reigned 1135–54), who was also a supporter of the Savignacs, confirmed the abbey’s foundation in 1138 and the monastery attracted the patronage of powerful local families. Despite this, Buildwas was a small and poor monastery. The monks probably worshipped and lived in temporary wooden buildings for as long as 20 years after the foundation of their house.

Merger with the Cistercians

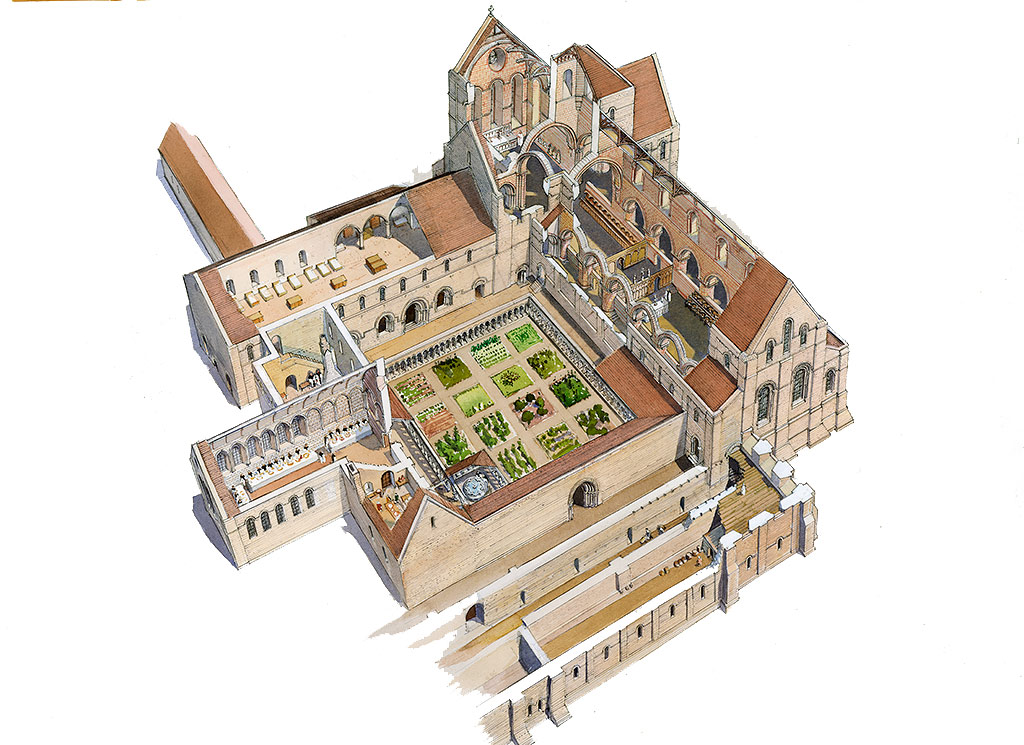

However, in 1147 all Savignac monasteries, Buildwas included, were absorbed into the much larger Cistercian order. Eight years later a talented and energetic man called Ranulf was elected abbot of Buildwas. He ruled the monastery until 1187. It was during this time that the abbey’s impressive stone church was completed, together with the monastery’s main buildings, which were arranged around a cloister to the north of the church.

The community at Buildwas would have consisted of Latin-literate monks – who sang the eight services that punctuated the monastic day – and also lay brothers, who were mostly illiterate and served God with their labour.

The endowment of the abbey continued to grow, the abbey’s estates ultimately extending as far away as Derbyshire. Ranulf’s talents did not go unnoticed. Between 1156 and 1157 St Mary’s Abbey, Dublin, and Basingwerk Abbey in north Wales were placed under his authority. The English were establishing their rule in Ireland at this time, and in 1172 Abbot Ranulf was Henry II’s representative at the Synod of Cashel, when Irish bishops accepted the customs of the English Church.

In 1171, Abbot Ranulf entrusted Alan, a lay brother of Buildwas, with a mission to Ireland on his behalf. Ranulf also travelled widely. He died in 1187 while on his way to the annual meeting of the governing Cistercian General Chapter at Cîteaux, the order’s mother house in France.

The Buildwas Books

By the time of Ranulf’s death, Buildwas was prosperous and vibrant. Its religious vitality is shown by its library, a substantial part of which survives. The statutes of the Cistercian General Chapter emphasised the importance of reading, and the monks were expected to spend a portion of each day reading in the cloister. So it was essential for all abbeys to maintain a well-stocked library.

A total of 54 manuscript books survive from Buildwas, more than from any other Cistercian monastery in England. Many date to Ranulf’s time as abbot and at least 15 were produced at the monastery. The abbey also received a gift of 20 manuscripts produced in France.

Most of the books are theological. In the 14th century, a survey of texts held in monastic libraries across England listed 111 in the library at Buildwas.

Image: A page from a late 12th-century manuscript from the library at Buildwas. A line above the decorated initial E reads: ‘The book of [the Cistercian abbey of] St Mary, Buildwas, written in the year AD 1176’

© British Library Board (MS Harley 3038 fol 7v)

13th-century prosperity

The abbey continued to prosper into the 13th century. Like Cistercian monasteries across England, it derived much of its income from the sale of fleeces from its flocks of sheep. Buildwas’s estates in Derbyshire alone were home to 500 sheep, and there were 300 more pastured in Herefordshire. These were traded with merchants in Flanders and Italy. The monastery’s stock also included cattle and goats. In 1277, Buildwas received permission to ‘assart’ or clear wooded land for cultivation. Papal taxation records from 1291 relating to the abbey’s estates in Shropshire and Staffordshire show that 60% of the income came from livestock, and 20% from arable farming.

There are occasional insights into the religious life of the monks. For instance, in 1239 the monastery received permission from the Cistercian General Chapter to celebrate the feast of St Milburga, an Anglo-Saxon monastic saint whose relics were enshrined at Much Wenlock Priory, about 5 miles away. In 1253, Buildwas and Basingwerk asked permission to observe the feast of St Winifred, a 7th-century Welsh saint.

Building works continued at the abbey. In about 1220 it received a grant of stone from quarries at nearby Broseley; in 1232 and again in 1255 it received gifts of timber from royal forests. These materials were probably used to build the infirmary and abbot’s lodging and also to renovate the church.

The abbey continued to add to its endowment, which also included properties in nearby Shrewsbury and Bridgnorth. Rich benefactors entrusted the monks with the salvation of their souls. A large chapel which projects south of the church was built at the end of the 13th century for the burial of patrons. Several tomb slabs can still be seen in its floor.

A series of setbacks

The monastery continued to flourish into the early decades of the 14th century. Its abbot was summoned to parliament on more than a dozen occasions between 1295 and 1324, and in the late 1320s the young Edward III praised the quality of religious life at the abbey.

However, in 1342 Buildwas’s abbot was murdered, and a monk called Thomas of Tonge was suspected of the deed. He was imprisoned at the abbey but somehow managed to escape. In the aftermath, rival factions of monks bitterly contested the election of a new abbot, and in the process the monastery’s possessions were squandered. By 1344, Buildwas had debts of £100.

Worse was to follow. In 1350 Welsh raiders broke into the monastery, pillaging its treasures and imprisoning the community. It is also likely that Buildwas was hit hard by the Black Death, which raged across Europe in the mid 14th century. In 1377 there were just six monks and in 1381 the number had fallen to four.

The abbey’s troubles continued into the 15th century. Its estates were damaged by the Welsh in 1404, and Buildwas also found itself in dispute with the Leighton family. Historic benefactors of the abbey, they attempted to force the monks to buy lands which their ancestors had granted to the monastery centuries before.

Dissolution

In 1521, religious life at Buildwas was condemned as ‘deficient in every respect’. The abbey was soon caught up in the religious politics of the reign of Henry VIII (1509–47). A great valuation of ecclesiastical property conducted in 1535 found that Buildwas had a net income of £111. The community consisted of the abbot and 12 monks, four of whom were accused of sexual immorality.

One year later, the abbey was dissolved along with many other ‘lesser monasteries’. The abbot received a pension of £16, and the monks were given permission to join a larger monastery (these were not suppressed until 1537–40) or to become priests in general society. The abbey’s lead and bells were valued at £94, and its moveable goods and other assets at a little over £57.

Post-Dissolution Buildwas

In July 1539, the abbey’s site and most of its property were sold to Sir Edward Grey, Lord Powis. He settled the estate on his illegitimate son, also called Edward, who converted the former abbot’s house and monastic infirmary into a mansion. A depiction of the house in a mid-17th-century map shows that this had a typical Elizabethan courtyard design.

By the late 17th century the house was owned by the Moseley family. It gradually declined in status and was partially demolished, becoming a tenanted farm. From the early 19th century the ruins started to attract the interest of antiquarians and artists, the latter including JMW Turner and John Sell Cotman.

In 1925, the ruins of the church and main cloister buildings were taken into state care. Since 1984, English Heritage has been responsible for preserving the site for future generations and interpreting the ruins for visitors.

Further reading

M J Angold et al., ‘Houses of Cistercian monks: Abbey of Buildwas’, in A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2, ed. A T Gaydon and R B Pugh (London, 1973), 50–59 [accessed 7 October 2020]

J Burton, Monastic and Religious Orders in Britain (Cambridge, 1994)

DM Robinson (ed.), The Cistercian Abbeys of Britain: ‘Far from the Concourse of Men’ (London, 1998)

DM Robinson, Buildwas Abbey (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2002)

JM Sheppard, The Buildwas Books: Book Production, Acquisition and User at an English Cistercian Monastery, c.1165–c.1400 (Oxford Bibliographical Society, 3rd series, vol. 2, 1997)

Related content

-

Visit Buildwas Abbey

The impressive ruins of this Cistercian abbey have an idyllic setting near the River Severn. Unaltered 12th century church and beautiful vaulted chapter house with tiled floor.

-

Buy the guidebook

This beautifully presented guidebook conducts the visitor on a tour of the abbey and provides a full history of monastic life there.

-

WHAT BECAME OF THE MONKS AND NUNS AT THE DISSOLUTION?

Discover what happened to the many thousands of monks and nuns whose lives were changed forever when, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England was closed.

-

ABBEYS AND PRIORIES

Learn about England’s medieval monasteries and uncover the stories of those who lived, worked and prayed in them.