Early Life

Jane (also Janna, Jeanne, Ginne or Jinny) was born in London and grew up near Charing Cross. She was the daughter of a German-born Scot, William Ryder, and Elizabeth de Boussy, from Antwerp. William was the principal harbinger of seven overseers at the Royal Mews for King James I (r.1609–25), responsible for all royal travel arrangements. Elizabeth was lavander (laundress) to the queen, Anne of Denmark.

William died in 1617, and two years later Elizabeth married James Maxwell, a groom of the bedchamber to princes Henry and Charles. Maxwell’s influence increased, becoming Garter Usher in 1621 and Black Rod in 1622. He became wealthy by accruing land, property, monopolies on trade, and tax exemptions. From 1628 into the 1640s, he was one of the king’s principal money raisers.

Through her stepfather, Jane grew up near the royal family and the court. She also witnessed Maxwell’s skill as a hard, canny operator who navigated the dangerous political waters of court and Parliament, furthering himself in the process. Later events showed that Jane was at ease among the great and powerful.

Jane would have had a private tutor and her letters are written in a fluent, educated, courtly style. There is no known portrait of her, but she was described in a report to the Derby House Committee in 1648 as ‘a tall, well-languaged gentlewoman, with a round visage and with pock holes [smallpox scars] in her face’.

Another, much later, description reveals a little more:

She was red haired, as her son Brome was, and was the most loyal person to King Charles in his miseries of any woman in England.

Life and Times of Antony Wood, antiquary, of Oxford, described by Himself (1672; ed. Andrew Clark, 1891), II.227

Marriage and Children

James Maxwell arranged Jane’s marriage in 1634. The groom was a country squire’s son, Brome Whorwood, four years her junior. Jane took a substantial dowry, while Brome was heir to country estates at Sandwell Park (West Bromwich, north-west of Birmingham) and Holton Park, near Oxford.

Jane clashed with her in-laws, perhaps because she was a confident, strong-willed, wealthy and cultured woman in what she may have considered a conservative backwater. Also, Scots ancestry, symbolised by red hair, was resented by the English.

Between 1635 and 1639 Jane had four children: Brome, a son, in 1635 (drowned in 1657); James, in 1636 (died after four months); a daughter, Elizabeth, in 1637 (died aged three) and another daughter, Diana, in 1639 (who lived until 1701).

War and secret work

Jane witnessed the rising tension between king and Parliament in the 1630s: her stepfather, as Black Rod, was in the middle of the stand-off. In the summer of 1642 it escalated into war, and Parliament took control of London, forcing Charles I to establish his court in Oxford. Holton Park was just 6 miles east of Oxford on the London Road, which enabled Jane, once again, to be in familiar company.

The court and military HQ of the king remained at Oxford until the end of the war in 1646. The Oxford to London road crossed the river Thame at Wheatley Bridge, a mile from Holton Park. This was a route used by the agents of both sides, seeking intelligence about their enemies. Jane quickly became a key part of the Royalist network.

She was, perhaps, the most important link between the king and wealthy London merchants, notably Sir Paul Pindar, who helped to finance the Royalist cause. In 1644 alone (records for the other years are lost) Jane arranged the movement of at least £80,000 (a buying power of about £9.4 million today) in gold coin from London to Oxford, concealed in soap barrels, smuggled through Parliamentary checkpoints.

This cash was vital to the Royalist war effort and probably kept Jane at Oxford and Holton Park until the Royalist surrender in June 1646. By then she was an experienced agent with over three years’ service. It is a testament to Jane’s cover that the Parliamentary army commander, Thomas Fairfax, used Holton Park as his HQ in May and June 1646, during which time Jane was surely, and often, present.

Following the King

For the next two years, Jane worked secretly for the Royalist cause, as the king negotiated with Parliament and with the Scots, attempting to contrive a way back to power. She tracked his movements to Newcastle and then Northamptonshire, and often returned to London where she maintained connections with London merchants.

In May 1647, she embezzled money from Parliamentary funds, and also arranged for more gold to be relayed to the king when he had taken residence at Hampton Court.

The Isle of Wight

In November 1647, Charles I fled Hampton Court for the Isle of Wight. Negotiations over a political settlement began again, though each side had few expectations, and the king made another abortive attempt to escape. Following a minor uprising in Newport, he was confined to Carisbrooke Castle in January 1648, with Colonel Robert Hammond as his jailer.

Jane arrived at Newport in December 1647 and planned, with others – Sir John Ashburnham, John Browne, Henry Firebrace, John Oglander and Silius Titus – to effect the king’s escape from Carisbrooke Castle. Jane was probably the ‘escape manager’. Coded letters were smuggled in and out, though double agents leaked what details they could discover to Parliament.

On 20 March 1648, the first escape attempt failed, when the king became stuck between iron window bars. A second attempt was planned, for which a hacksaw and nitric acid were smuggled in. However, on 20 April Jane advised Henry Firebrace to pretend in correspondence that the escape was being abandoned, because she suspected betrayal.

Meanwhile, Jane chartered a ship in London and proceeded to Queenborough on the river Medway, intending to take the king to Holland. Others would convey the king from Carisbrooke across the Solent and overland to Queenborough.

Jane waited for five weeks, but the attempt on 29 May also failed when the king’s guards, who had been bribed to turn a blind eye, betrayed him.

Read more about Charles I at CarisbrookeUndeterred

Despite these escape attempts, plans for further negotiations were agreed. The king, still watched by Colonel Hammond, could receive private visitors at the house of William Hopkins in Newport. By 19 July, Jane was nearby and two lost letters from her precipitated an earthy response from the king – the suggestion from him of a private meeting, a sexual liaison. In a letter to Henry Firebrace, Jane expressed the conflict she felt between duty and personal feelings.

It was almost a whole month later, and after many impatient letters to Jane from the king, that Hammond relaxed sufficiently to allow the king more personal freedom in advance of the negotiations in September. On 28 August, Jane met the king alone at the Hopkins’s house, and several times more in the next few days there, and at Carisbrooke. That this was in part a sexual arrangement is clear.

King and Parliamentary commissioners began negotiating on 15 September, but both sides knew this was insincere and pointless, as the army hardliners in London would never agree to a moderate settlement. On 13 November, Jane wrote warning the king and advising escape, as she knew that Parliament would insist on absolute compliance with their terms. On 25 November, Jane was in Newport and the means were in place for an escape, but the weary king dismissed the attempt.

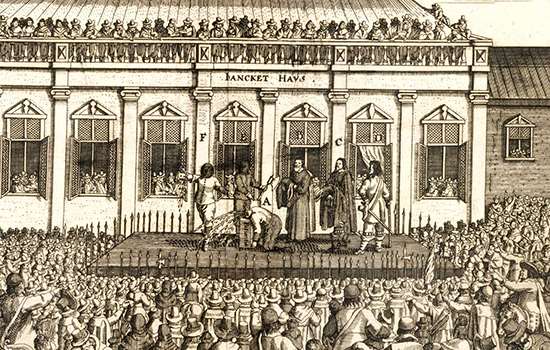

The king was taken to the mainland and kept for three weeks at Hurst Castle, then conveyed to London. After a brief trial, he was executed on 30 January 1649. Jane’s cause, one she had so faithfully, carefully and skilfully followed for so long, was lost.

Later Life

It is unlikely that Jane’s activities were ever fully known by Parliament. She had a brief spell in prison when her embezzlement of Parliamentary funds was discovered in 1651, but was released when her mother repaid the money.

Jane was 39 and her marriage had been strained since the war. Brome was openly living with Kate Allen, a baker’s daughter from Oxford, elevated from servant at Holton Park to its mistress in place of Jane. Throughout the 1650s Brome was violent, on one occasion beating Jane so violently that she was taken to Oxford for treatment and refuge. There followed almost 30 years of litigation. Brome was repeatedly censured and instructed to pay Jane alimony of £300 per year. He consistently avoided doing so and in 1657 wrote ‘If she were dying and a halfpenny would save her, I would not give a halfpenny.’

At the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Jane’s services to the new king’s father did not receive due recognition, which is strange. Men were usually rewarded with government posts and monopolies, from which they would prosper; women might be gifted precious jewellery or money. It is probable that Jane was not among the many who petitioned the king for position and reward. Her co-conspirators on the Isle of Wight, Henry Firebrace and Silius Titus, were handsomely rewarded.

On Brome’s death in 1684, Jane was not in his will, though their daughter Diana and her husband had Holton Park for their lifetimes. Jane died a few months later at Holton in 1684, aged 72. She was in a state of ‘genteel poverty’ with modest personal possessions valued at £40 – about £4,500 in modern terms.

Legacy

Jane Whorwood’s life has been brilliantly and painstakingly traced by her biographer John Fox, yet much remains unknown. She was a complex character at a time when families were split by politics, religion and civil war. Jane’s confident character and secret activities may have affected family relationships; three sisters and her mother-in-law excluded her from their wills. Her marriage proved to be disastrous and Jane suffered humiliation, violence, and bad faith from her husband.

In her role as secret agent, Jane was devoted to the king’s cause – a commitment surely forged in childhood – and faced constant danger in his service. Jane was a meticulous planner: her success as a gold runner to Oxford, breathtaking in its scope, was a major contribution to the Royalist war effort and deserves wider recognition. Later, Jane’s efforts to free the king from the Isle of Wight throughout 1648 were tireless, despite the knowledge that her enemies were watching.

Had the rest done their parts as carefully as Whorwood, the King would have been at large

William Seymour, Marquess of Hertford, to William Hamilton, Earl of Lanark (Jane’s brother-in-law), June 1648

By Paul Pattison, Senior Historian

Further reading

Fox, J, The King’s Smuggler: Jane Whorwood, Secret Agent to Charles I (Stroud, 2010)

Fox, J, ‘Whorwood [née Ryder], Jane’,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004–16) (subscription required; accessed 16 Feb 2021)

Poynting, S, ‘Deciphering the king: Charles I’s letters to Jane Whorwood’, The Seventeenth Century, 21:1 (2006), 128–40

Read more

-

Visit Carisbrooke Castle

Defender of the Isle of Wight for more than a thousand years

-

History of Carisbrooke Castle

Find out more about the history of the castle, which has been a central place of power and defence on the Isle of Wight for a thousand years.

-

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

-

Women in History

From great medieval queens to nurses in the First World War, the role of women throughout English history has often been overlooked