Early History

Roman occupation in the area around Carisbrooke has been suggested but never proved. The earliest certain use was for a pagan Anglo-Saxon cemetery of the 6th century. Three graves were discovered during excavations.[1]

In about 1000 this prominent hilltop, dominating the centre of the island, became the site of a rectangular fortification, formed of an earthen bank, later faced with a stone wall, and containing large timber buildings. This was probably an Anglo-Saxon burh (or fortress/fortified settlement), built to provide a refuge against Viking raids.

The Norman Castle

Shortly after the Norman conquest, the burh was converted into a castle to secure the island for the Norman invaders. A defended enclosure was formed in one corner of the Saxon burh by digging deep ditches within it.[2]

In 1100 the Isle of Wight became part of a powerful lordship, created by Henry I (reigned 1100–35) for Baldwin de Redvers, one of his key supporters. The island remained in his family until 1293. It was probably Baldwin who created the present massive motte-and-bailey castle which still dominates the hilltop.

After Henry I’s death Baldwin supported his daughter, Matilda, in her claim to the throne when the king’s nephew, Stephen, took it for himself, resulting in civil war. In 1136 Baldwin probably intended to defend Carisbrooke, but was forced to surrender to King Stephen when its water supply ran dry.

By this time the castle had stone walls on its banks,[3] but its internal layout is uncertain. The castle chapel, also a parish in its own right, was probably on the site of the present chapel, with an enclosure behind it in what is now the Privy Garden.[4]

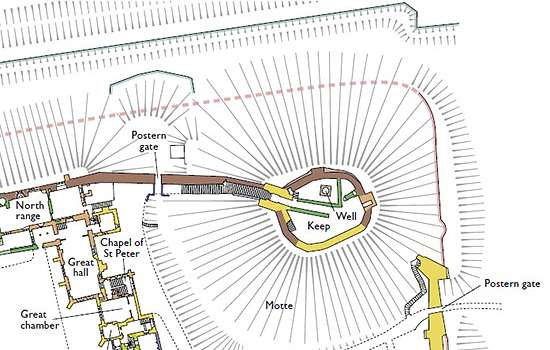

Download a plan of Carisbrooke CastleIsabella de Fortibus and her Successors

The last of the de Redvers, Countess Isabella de Fortibus, shaped the castle interior into its present form. As well as work to the defences, she concentrated her attention on creating a residence fit for a great magnate. She built the existing, much altered great hall with her chamber at one end and her private chapel at the other,[5] together with numerous other buildings around a central courtyard. In 1293, in the last days of her life, she sold her estates to Edward I, and the castle has remained Crown property ever since.[6]

For the rest of the Middle Ages the castle was governed by a rapid succession of Crown-appointed lords of the island. Such work as was done focused on the defences, particularly during the wars with France. The Isle of Wight was raided five times between 1336 and 1370 and the castle was besieged in 1377. At the end of the 14th century William de Montacute (lord of the island 1386–97) remodelled the great hall and rebuilt the chamber block adjoining it.

In the early 16th century the importance of the castle declined as Henry VIII adopted a policy of coastal defences.[7]

Find out more about Isabella de FortibusGeorge Carey

This changed when Elizabeth I (r.1558–1603) appointed her cousin George Carey captain of the island in 1583.

He remained captain until his death in 1604 and had a strong sense of his own importance. He began by rebuilding the domestic buildings of the castle, which had fallen into decay, to provide accommodation worthy of a great magnate. The hall block and St Peter’s Chapel were radically changed with the insertion of an upper floor.[8] Adjoining the hall he added a new range, known as Carey’s Building, with 17 rooms and a long gallery.

With the threat of Spanish invasion Carey made some modest additions to the defences in 1587. In the next invasion scare of 1596–7, however, he persuaded the queen and the local gentry to pay for the creation of a major, modern artillery fort at Carisbrooke. This took the form of a low, roughly rectangular rampart nearly a mile long, with five bastions. These defences were completed in 1602, but were never used in action.[9]

Buy the Guidebook to Carisbrooke CastleThe Civil War and Charles 1

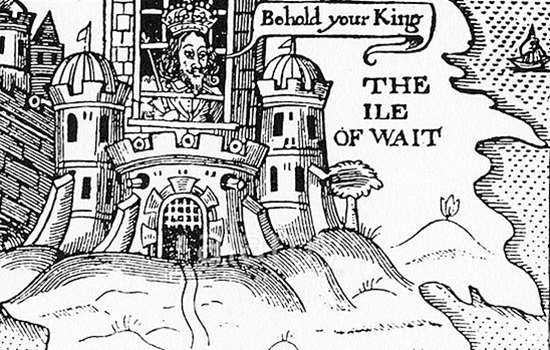

At the outset of the Civil War in 1642 the castle passed into the hands of the Parliamentary forces. Its principal use until 1660 was as a prison for important Royalists, the most notable inmate being Charles I in 1647–8. Later it was used as a prison for his youngest son and for his daughter, Princess Elizabeth, who died here in 1650, at the age of 14.

Charles I came to the island in November 1647 after he had escaped from house arrest at Hampton Court, in the hope that he might be able to act more freely. But he quickly found that he was again a prisoner, this time in the castle. He was housed with some ceremony in the hall range, attended by members of his own household. An enclosure on the east side of the castle was converted into a bowling green for him.

Charles made two unsuccessful attempts to escape, in March and May 1648. In September he was removed to Newport for unsuccessful negotiations with Parliament, and then by stages to London and his execution in Whitehall on 30 January 1649.[10]

Find out more about Charles 1's Escape AttemptsA Changing Role

Thereafter the significance of the castle declined as defences moved back to the coast. Carisbrooke was the occasional residence of the governors of the Isle of Wight, some of whom, notable Lord Cutts (governor 1692–1706) and the Earl of Cadogan (1715–26), carried out repairs and alterations. In 1738 the Chapel of St Nicholas was demolished and rebuilt in Georgian style.[11]

By the mid-19th century the castle was no longer used as a residence, but still had a residual military role as a base for the Isle of Wight Artillery Militia. The roof and floors of the gatehouse had been removed and Carey’s building had been reduced to a ruin. Many of the remaining buildings were in poor repair. It was by then also becoming much visited as a tourist attraction. It passed into the care of the Office of Works in 1856.

The first restoration was carried out by Philip Hardwick in that year. He converted the Constable’s Lodging, at the southern end of the hall range, and the L-shaped block in the south-east corner of the castle to their present form before the funding ran out. He also demolished the Chapel of St Nicholas to create a romantic ruin.

Carisbrooke as monument

The major influence on the castle’s present form, however, was Percy Stone, an architect who was also the island’s historian. He published the first study of the castle’s history and architecture in 1891.[12] He was helped by renewed royal interest in the castle when Princess Beatrice, Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter, was appointed governor in 1896 in succession to her husband, Prince Henry of Battenberg.

Stone first restored the gatehouse, replacing its roof and one upper floor, to make the first Isle of Wight Museum, opened in 1898 in memory of Prince Henry. In 1904 he restored the Chapel of St Nicholas to its present quasi-medieval form. Its internal appearance, however, results from its use as the island’s war memorial commemorating the 2,000 men from the Isle of Wight killed in both world wars.

In 1913 Princess Beatrice had the hall range and Constable’s Lodging adapted and modernised to become her summer residence, which she continued to use until 1938.

Since the Second World War, the castle has remained largely as a monument. It is used occasionally for island ceremonies but is primarily a tourist destination. It is also the home of the Isle of Wight Museum, which moved after Princess Beatrice’s death in 1944 into the more spacious accommodation of the hall range, where it remains.

About the Author

Dr Christopher Young is a heritage consultant and former Head of International Advice at English Heritage. He led excavations at Carisbrooke Castle between 1976 and 1983, and is the author of the English Heritage guidebook to the castle.

Find out more

-

Visit Carisbrooke Castle

Explore the castle at the heart of the Isle of Wight, steeped in history from the Norman Conquest to Charles I. Home to the famous Carisbrooke donkeys.

-

Isabella De Fortibus

Countess Isabella de Fortibus was one of the greatest heiresses in 13th-century England. Her life story illustrates how powerful women of noble birth could become in the Middle Ages.

-

A Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke

Read about King Charles I’s time as a prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle, including his many escape attempts.

-

Jane Whorwood, Royalist Spy

Jane Whorwood was one of the key agents behind attempts to free Charles I from captivity on the Isle of Wight, notably from Carisbrooke Castle, in 1648.

-

Princess Beatrice

Princess Beatrice was the youngest of Queen Victoria’s nine children. As Governor of the Isle of Wight, she had strong links with Carisbrooke Castle.

-

Buy the guidebook

This beautifully illustrated guidebook provides a full tour and history of the castle and its occupants.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of Carisbrooke Castle to discover how its buildings have developed over time.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

Footnotes