The Rise and Fall of Andrew Harclay

How the Earl of Carlisle’s career, in which Carlisle Castle featured prominently, reflects both the rewards and the risks of engagement with Anglo-Scottish border politics.

UPS AND DOWNS

The people of the Middle Ages liked the idea of Fortune’s Wheel, endlessly turning to raise men and women to riches, fame and power, and then casting them down again.

Few medieval Englishmen can have embodied this concept more completely than Andrew Harclay (c.1270–1323), a Cumbrian squire who rose to be an earl, only to perish miserably less than a year later as a convicted traitor.

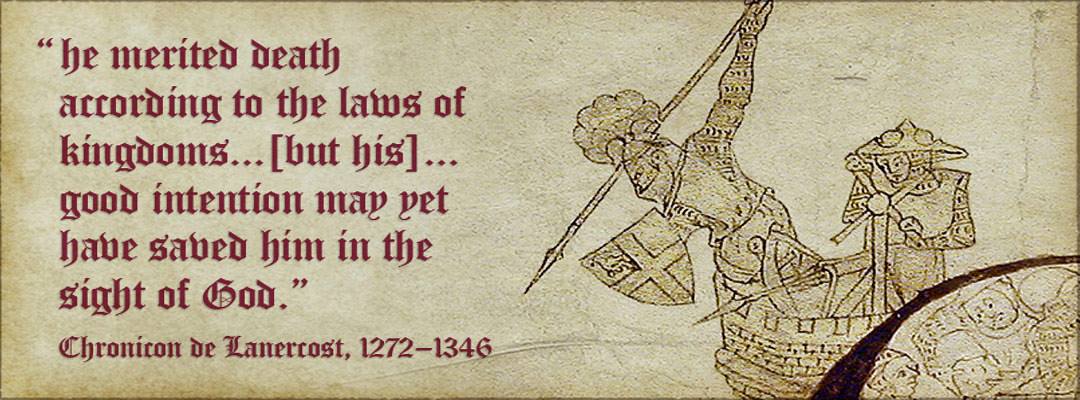

Carlisle Castle featured prominently in the triumphs and disasters of Harclay’s career, which was above all that of a soldier in the Anglo-Scottish wars which broke out in 1296. He gave an impressive demonstration of his military talents in 1315, when he led the defence of Carlisle against an all-out Scottish attack led by King Robert Bruce in person. A contemporary drawing (above) shows him leaning over a wall to hurl a spear at the enemy below.

GUERRILLA WARFARE

Harclay was captured shortly afterwards, perhaps in a raid over the border, but he was soon released, and took the lead in defending north-west England against further attacks. It was a war of forays and skirmishes, in which the participants probably got to know one another well as they negotiated truces and ransoms, and fought together, their shared identity as fellow borderers sometimes counting for more than royal orders.

When in March 1322 Harclay was made an earl – an astonishing promotion for a man of his relatively obscure origins – his elevation was not a reward for resisting the Scots, but rather for defeating a rebellion against Edward II at the Battle of Boroughbridge. Ironically, this victory saw him drawing his men into formations learned from his Scottish adversaries.

ROBERT THE BORDERER

Edward II lacked judgement and steadiness of purpose. Unrealistically he refused to abandon his claim to be King of Scots, but failed to protect the north of England against devastation.

As a result Harclay probably felt little gratitude for his own ennoblement, and about the end of 1322 he decided to try to end the war through a treaty with Robert Bruce negotiated without Edward’s knowledge, accepting that England and Scotland should be separate kingdoms. By birth King Robert was a borderer like Harclay, and it probably seemed natural to both men that disputes over the implementation of the treaty should be settled by juries made up of six Englishmen and six Scots.

This, after all, was exactly how lawsuits under the laws of the marches (the border regions) were decided.

ACCUSED OF TREASON

Edward II soon learned of the treaty. Harclay’s meteoric rise, and the way he sometimes exploited it at the expense of local rivals, had made him enemies. Acting on their outraged king’s instructions, a group of them took the earl by surprise and arrested him in the great hall of Carlisle Castle.

After a perfunctory trial he was condemned to death as a traitor, and on 3 March 1323 he was hanged, drawn and quartered on Harraby Hill, just south of the city. In a speech at the foot of the gallows, Harclay declared his good intentions in making peace with the Scots.

His mistake had lain in attempting to achieve this through methods that alienated him from King Edward – an error of judgement that cost him his life.

By Henry Summerson