The Norman Castle

Archaeological evidence shows that there was activity in this area in Roman times (with a Roman cemetery lying across the site)[1] and perhaps even earlier, but it was William the Conqueror who first established a castle here.[2] When he marched north in 1068 to suppress a rebellion against his rule, he built a series of castles as he went, including one here where Clifford’s Tower now stands.[3]

The Norman motte-and-bailey castle saw several violent incidents during its earliest years, including further revolts and an attack by Danish invaders. As the political situation settled down in the 1070s, however, the damage of these early years was repaired, and the castle, built largely of earth and timber, probably survived relatively unaltered through most of the 12th century.

Download a Plan of Clifford's Tower

The Mass Suicide and Massacre of 1190

The castle of York was the setting for one of the most notorious events in English history: the mass suicide and massacre in March 1190 of York’s Jewish community.[4]

Tensions between Christians and Jews had been increasing throughout England during the 12th century, partly because many people were in debt to Jewish moneylenders and partly because much crusading propaganda was directed not only against Muslims but also against Jews. Anti-Jewish riots in several cities followed the coronation of the crusader king Richard I in 1189, and a rumour (untrue) was put about that he had ordered a massacre of the Jews.

In York, as described by William of Newburgh and other contemporary chroniclers, about 150 people from the Jewish community were given protective custody in the royal castle, probably the site of Clifford’s Tower.[5]

Somehow, though, trust between the royal officials and the Jews broke down. The officials, finding themselves shut out from the tower, summoned reinforcements to recapture it. These troops were joined by a large mob, which soon ran out of control, incited by both anti-Jewish preachers and local gentry eager to escape their debts.

On 16 March, the eve of the Sabbath before Passover, when the Jews realised that there would be no safe way out for them, a rabbi urged his fellow-inmates in the tower to commit suicide rather than fall into the hands of their persecutors. Heads of households killed their own families before killing themselves, and the wooden tower itself was set on fire.

According to several accounts a number of Jews did survive and came out of the tower under an amnesty, only to be murdered by the attackers. A plaque at the base of the mound, commemorating these events, was installed in 1978.

Though Jewish life did in fact revive in York within a few years of the massacre, it came to an end a hundred years later, in 1290, when Edward I expelled all Jews from England.[6] This time their exile lasted until the 17th century.

Read more about the Massacre at Clifford’s TowerThe Medieval Castle

The tower burnt down in 1190 was rebuilt very shortly afterwards. Further repairs and rebuilding, some in stone, took place in the castle during the early 13th century.[7] Then in the middle years of that century, as war with Scotland loomed, King Henry III decided to build a completely new stone tower on the mound.

A writ of March 1245 may refer to the construction of the tower. It orders Master Henry the mason and Master Simon the carpenter to advise the sheriff on strengthening the castle's defences.[8] Master Henry is often identified as Henry of Reyns, master mason of the new abbey at Westminster. At the abbey, as at Clifford's Tower, English architectural detailing was applied to a plan influenced by French prototypes.[9]

Documentary sources show that construction was intermittent and the tower was probably not finished until the 1270s, possibly not until the 1290s.[10]

Despite the regional and national importance of York, its royal castle did not generally act as a royal residence. Together with Clifford's Tower it was instead used chiefly for administrative purposes, notably for imprisonment, for storage and for judicial sessions. Occasionally it acted as a home for the Exchequer and its various treasuries when wars against the Scots caused the government to relocate to the north of England. It also housed an important royal mint.[11]

The castle's buildings, particularly Clifford's Tower, whose mound was scoured by floods of the river Fosse, fell more than once into disrepair.[12] By 1360, several of the structural defects which are visible today had already appeared.[13]

Read a Description of Clifford’s Tower

The Tower in Decay

The history of the castle and Clifford’s Tower during the 15th and 16th centuries is obscure. Accounts of Henry VI, Richard III and Henry VIII suggest that several buildings were ruinous, and efforts were concentrated on maintaining a small number of them as gaols.[14] In 1540, just three years after Robert Aske (one of the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace)[15] had been hanged ‘on the height of the castle dungeon’,[16] John Leland wrote that ‘the arx is all in ruin’.[17]

In 1596–7 a public scandal arose when the aldermen of York accused the gaoler, Robert Redhead, of trying to demolish the derelict tower and sell the stone for lime-burning.[18] Contemporary correspondence about these events contains the first recorded use of the name ‘Clifford’s Tower’.

The name is sometimes interpreted as evidence that the Clifford family claimed the post of constable to be hereditary.[19] Alternatively, it may refer to the rebel Roger de Clifford, who was executed after the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322 and whose body was displayed on a gibbet at the castle.[20]

BUY THE GUIDEBOOK TO CLIFFORD’S TOWER

War and Explosion

After a brief period when Clifford’s Tower passed out of royal ownership, in 1643 it was occupied again by a royal garrison during the Civil War. The building was re-roofed and re-floored, apparently at the behest of Queen Henrietta Maria, creating storage rooms for ammunition and a gun platform on the roof. The forebuilding was largely reconstructed.[21]

The city fell to Parliamentarians the following year. The tower continued to be occupied by a garrison of between 40 and 80 men and it may also have served occasionally as a prison. The Quaker George Fox was imprisoned here for two nights in 1665, on his way to Scarborough Castle.[22]

The garrison’s dissolute behaviour caused discontent among the citizens of York, who called for the demolition of the tower, scathingly nicknamed ‘the Minced Pie’. On 23 April 1684 the interior was partly gutted by fire, allegedly as a result of the firing of a ceremonial salute for St George's Day. Destruction was not total, though, and parts of the building remained in use for storage, while cannon were still positioned on the roof.[23]

By 1699, however, when Clifford’s Tower was released to freeholders, sketches of the interior by Francis Place show that it was completely roofless.[24]

Gaol and Monument

The 18th century was a period of changing ownership for the tower and mound. Clifford’s Tower was treated as a garden folly and possibly as a stable or cattle shed.

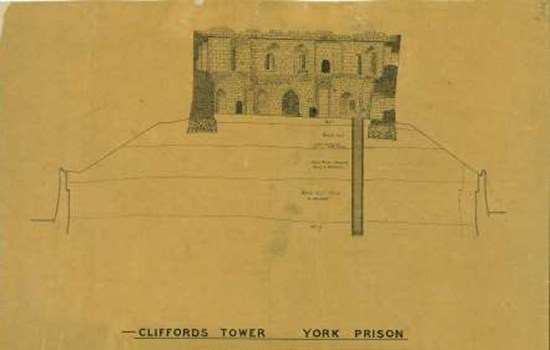

In marked contrast, the former bailey of the castle was redeveloped as a prison. New courthouses and gaol buildings were built, until in the 1820s and 1830s the prison encompassed the entire castle area. The mound and tower were enclosed and effectively hidden from view. Clifford’s Tower was accessible only with permission from a magistrate.

In 1902 a radical campaign of repairs and investigations was undertaken by Mr Basil Mott, including the partial reconstruction of the mound in an effort to underpin the south-east lobe of the tower with buried concrete ‘flying buttresses’. During these works, the most detailed archaeological investigation to date of the internal structure of the mound was carried out.[25]

On 30 March 1915, Clifford’s Tower was taken into state guardianship.[26] The structure was repaired and public access improved in 1935 with the demolition of the surviving 19th-century prison buildings, notably the wall enclosing the mound on its north and west sides. The lower parts of the slope were restored to their presumed medieval profile, and a stairway leading up to the forebuilding in a straight line was created, replacing a spiral path.[27]

About the Author

Jeremy Ashbee is the Head Historic Properties Curator at English Heritage. He specialises in the study of medieval palaces and castles.

Find out more about Clifford’s Tower

-

The Massacre of the Jews at Clifford's Tower

An account of the tragic events of 1190 and the rise of anti-Semitism in medieval England.

-

Description of Clifford's Tower

Discover what the surviving architectural features of Clifford’s Tower tell us about its history and function.

-

Why is Clifford's Tower Important?

Clifford’s Tower is the largest surviving structure of York Castle. Find out why it still matters and what it tells us about the city of York.

-

Download a plan of Clifford's Tower

Download plans and cross-sections showing how Clifford’s Tower has developed over time.

-

Research on Clifford's Tower

Find out what academics have uncovered about Clifford’s Tower and the role it has played in history.

-

Sources for Clifford's Tower

A list of the main written, visual and material sources for further study of Clifford’s Tower.

-

Buy the Guidebook

Explore the site of Clifford’s Tower and read about its history in the official guidebook.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.