Church and castle

A 17th-century survey describes the interesting relationship between the church and the Norman castle: the church ‘adjoygnethe so neere an owlde decayed fortification as they bothe seem to possesse … antiquity and poverty’.

The church actually lies within the bailey (the outer defended area) of a Norman motte-and-bailey castle. The remains of the motte – a conical mound on which a timber fortification stood – can still be seen to the west of the 19th-century church.

Dating the church

The church is variously described as ‘Norman’ or ‘Saxo-Norman’ – terms which demonstrate that it is difficult to date the church accurately.

Historians have shown that the parish of Yedeven (the predecessor of both Edvin Loach and Edwyn Ralph) existed in late Anglo-Saxon times (by the 10th or early 11th century) and that it ‘belonged to’ the more important local church (known as a minster church) of Clifton-upon-Teme. It is reasonable to think that a very small Anglo-Saxon church was replaced by Edvin Loach ‘old church’ (not, of course, old at this time) soon after the Norman Conquest, perhaps by an early member of the Loges family such as Herbert (the lead tenant of the manor mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086).

The herringbone-pattern stonework on the north and south walls is a feature of early Norman churches in this part of England, as is the style of the simple south doorway. However, fragments of stone sculpture in the style known as ‘Hereford School’ might point to a slightly later date for the church, in the 12th century.

Some Norman architectural fragments from the church are preserved by English Heritage in the Archaeological Collections Store at Wrest Park.

Description of the church

The church has a simple layout, essentially a single space divided into three areas – the chancel (east), nave (centre) and tower (west).

Locally quarried soft sandstone rubble was used to build the walls. The corners, and window and door edges, however, were carved from harder tufa – a type of carboniferous limestone, also locally quarried in the Teme valley. The two types of stone differ in colour and texture.

Interesting features include the herringbone arrangement of the wall masonry, and the doorway with its bulky tufa lintel. (A 19th-century local historian recorded the tradition that this lintel was a relic from an ancient hermitage at Southstone Rock, near Stanford-on-Teme.) This must have been rather a dark building, as it had narrow windows high in the walls. Just the lower half of one 11th-century window survives by the south door.

The east end of the church housed the altar, and the west end (nave) was the area where the congregation sat (they would have originally stood). Vertical ‘scars’ in the stonework of the long walls towards the east end may mark the position of pilasters (pillars attached to the walls) that may have framed and supported a rood screen. This was a timber screen that separated the choir from the nave, while still allowing the parishioners to see the priest and altar in the choir.

Later history

Like most early churches, this one was modified in later centuries. The east end, including parts of the north and south walls, was apparently rebuilt in the 12th century. In the 16th century the tower was added at the west end. It was built on two levels and lit by square-headed windows. A wooden screen may once have divided the tower from the nave.

The church continued in use until the 1860s, when the new church (not in the care of English Heritage) was built. This is a small scale but rather fine example of 19th-century church architecture. It was designed in the Early English style by the great Victorian architect Sir George Gilbert Scott.

The old church gradually became dilapidated, although its roof was still intact as late as the 1890s.

Beyond the church

Outside the church, the boundary of the Norman castle bailey formed a roughly square enclosure about 70 metres (229 feet) wide. It was surrounded by a ditch about 4 metres (13 feet) wide, which is now visible as a shallow depression in the field to the south.

The higher level of the graveyard, especially at its western end, is accounted for by many generations of burials in this small rural community.

Further reading

Historic England entry for Edvin Loach Old Church

Merlen, RH, The Motte-and-Bailey Castles of the Welsh Border (Ludlow, 1987)

Salter, M, The Castles of Herefordshire and Worcestershire (Malvern, 2000)

Waddington, SK, ‘The origins of Anglo-Saxon Herefordshire: a study in land-unit antiquity’, University of Birmingham PhD thesis, 2013 (accessed 14 Nov 2018)

Wyatt, A, A History of Edvin Loach (Bromyard and District Local History Society, 2014)

Related content

-

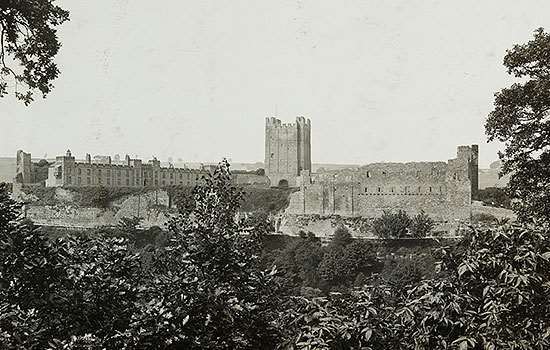

History of Middleham Castle

A childhood home of Richard III, Middleham Castle developed from its Norman core into the palatial residence of the powerful Neville family.

-

History of Richmond Castle

Read a full history of Richmond Castle, from its Norman origins to its use as a base of the Non-Combatant Corps during the First World War.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

-

English medieval castles

Discover the stories held within the walls of England’s greatest fortifications and learn about the rise and fall of the medieval castle.