The first castle at Farleigh Hungerford

Farleigh Hungerford Castle was begun before 1383[1] by Sir Thomas Hungerford (c 1328–1397). Born of a family which had achieved only modest influence in Wiltshire, Thomas prospered as chief land steward of Edward III's fourth son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Allegedly because of Gaunt's influence, he was elected Speaker of the Commons in the Parliament of January 1377, the first formally recorded holder of that office.[2]

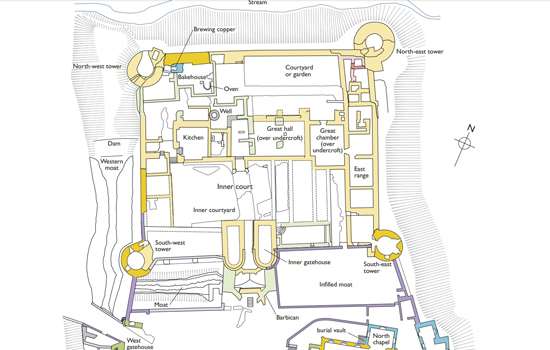

Essentially a symbol of his rising status, Sir Thomas’s building (which later became the inner court of the extended castle) was a fortified mansion ranged around a rectangular central courtyard, with a tall tower at each corner, in the ‘quadrangular’ style fashionable during the 1370s and 1380s.

The castle was built on the site of an earlier, possibly 13th-century manor house, which Sir Thomas had bought in 1369. Although the location lacked strategic importance or strong natural defences, it was remote from the influence of rival landowners, making it suitable for the seat of a potential Hungerford dynasty.

Indeed, Sir Thomas chose to be buried here rather than at his larger property in Heytesbury, Wiltshire. His fine monument survives in the castle chapel, which he built to serve as the parish church.

The Castle Extended

The castle was greatly enlarged by Sir Thomas’s son Walter, 1st Lord Hungerford (1378–1449). Much the most distinguished member of the family, Walter raised the Hungerfords to national importance.[3] Following the family allegiance to the royal House of Lancaster, he served with Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt (1415) and throughout the king’s subsequent triumphs in France.

Created a Knight of the Garter, Walter was appointed a guardian of the baby Henry VI on Henry V’s death, and served as Treasurer of England (1426–32). He died a very rich man, owning more than 100 manors and other estates, mainly in the west of England.

According to tradition, Walter’s additions to the castle were mainly financed by the ransoms of his French prisoners.[4] Probably between about 1430 and 1445, he enhanced the buildings within the inner court, probably refashioning the great hall and bedchambers, and added a barbican reinforcement outside its gates.

Walter also constructed the outer court with its curtain wall, towers and gatehouses, thus almost doubling the size of the castle. This new court enclosed the former parish church, which Walter adopted and improved as the castle chapel. He also built a house for the priests who served it.

The Chapel Wall Paintings

The chapel of St Leonard stands in the outer court of Farleigh. One of the most notable features of its interior are the remains of 15th-century wall paintings primarily commissioned by Walter, 1st Lord Hungerford, when he refurbished the chapel in the early 1440s.

Featured in the wall paintings is a large figure of St George, patron saint of England and of the Order of the Garter, and a now scarcely traceable figure of a kneeling knight wearing a tabard of the Hungerford arms.

Unfortunately the chapel wall paintings have suffered badly since their discovery in 1844. The red background results from well-meant but disastrous preservative treatment with hot wax, applied between 1931 and 1955 and removed by English Heritage in the 1970s. The paintings originally had a pale background.

As part of a wider fundraising campaign, English Heritage has launched the ‘Save our Story’ appeal to support the much needed conservation of the wall paintings in our care, such as those seen at Farleigh. With the help of the public we hope to bring in the specialist knowledge and technology required to save these rare and delicate works from serious deterioration or even permanent loss, in the future. Learn more about the campaign and the other wall paintings in our collection in need of conservation work.

Save our Wall PaintingsDisasters and Scandals

Misfortune and scandal dogged the Hungerfords and their castle during the struggle for the English Crown between the royal Houses of York and Lancaster, known as the Wars of the Roses, and the early Tudor period.

Robert – the 3rd and last Lord Hungerford (c 1423–1464) – and his eldest son, Sir Thomas (c 1439–1469), were both executed for their adherence to the Lancastrian cause, and in 1462 the castle was confiscated by the Yorkist regime.

In 1486 Sir Walter Hungerford II (c 1441–1516) regained ownership of the castle, as a reward for his personal support for the victorious Henry VII at the Battle of Bosworth in the previous year. Walter’s son Sir Edward rebuilt the east gatehouse; but after his death in 1522 his widow, Agnes, was hanged for having murdered her first husband – Sir Edward’s steward – and having burned his body in the castle’s kitchen furnace.[5]

Sir Walter Hungerford III (1503–40) imprisoned his third wife, Elizabeth, in the castle for nearly four years and frequently attempted to poison her. She survived only by drinking her own urine and eating food secretly supplied by local women.[6]

Walter Hungerford III became the local agent of Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell, and was created Lord Hungerford of Heytesbury. He was, however, later convicted of treason, witchcraft and the then capital crime of homosexuality, and was executed alongside Cromwell on 28 July 1540. Afterwards the castle was again confiscated by the Crown.

Read more about Walter Hungerford III’s fallThe castle was redeemed for a large sum in 1554 by Sir Walter Hungerford IV (c 1532–97), known as ‘the Knight of Farleigh’ because of his prowess at field sports. He probably updated the (now vanished) hall range of the inner court, adding its Elizabethan-style windows and perhaps its carved panelling or wall-paintings depicting knights in armour.[7]

Further improvements were made by his brother, Sir Edward Hungerford II (d.1607), and his great-nephew and heir, Sir Edward Hungerford III (1596–1648). These included the updating of the state rooms, the addition of heraldic stained glass to their windows and the redecoration of the chapel.

Find out more about the Hungerford family scandals

The Castle in the Civil Wars

Having married into a prominent London Puritan family, Sir Edward Hungerford III became the commander of Parliament's Wiltshire forces during the first Civil War (1642–6). He proved rather incompetent, however, abandoning Salisbury, Malmesbury and Devizes to the Royalists.

The castle was seized and garrisoned by Sir Edward’s Royalist half-brother John. After witnessing a few skirmishes – the only known military actions in its history – it was regained in 1645 for Sir Edward, who died there in 1648. He is commemorated by a splendid monument in the north (or side) chapel, which was redesigned for it by his widow, Lady Margaret (d.1672).

Sale and Decline

Known as ‘the Spendthrift’, Sir Edward Hungerford IV (1632–1711), last of the Hungerfords of Farleigh, was legendary both for his extravagance – allegedly paying 500 guineas for a wig, for example – and for his debts. When all attempts to repay these failed, he sold the castle in 1686 to the Baynton family, who lived there until about 1702.

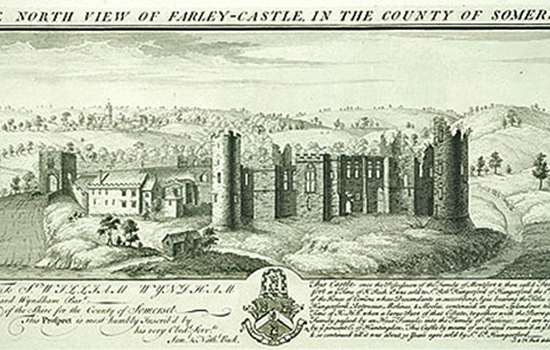

The castle was sold for salvage in 1705 to the Houlton family. During the following decades the castle was systematically plundered for its materials and fittings. Only the priests’ house remained inhabited, though the chapel was later repaired. It had become a ‘repository of curiosities’ – armour and fanciful furnishings – by the 1830s.

Consolidation and Controversy

These changes were recorded in the guidebooks published between 1852 and 1879[8] by the Revd JE Jackson, who partly excavated the castle and helped to preserve its chapel. The ivy-covered and tree-grown ruins were an immensely popular subject for artists.

In 1915 the Ministry of Works assumed guardianship, and during the early 1920s began stripping foliage from the crumbling walls and repointing stonework. This work was condemned by Country Life magazine as ‘the icy touch of a mechanistic and bureaucratic age’,[9] but by 1930 the controversy had subsided.

In 1959 the priests’ house, until then still used as a farmhouse, was bought and restored. In 1984 responsibility for the castle passed to English Heritage, and conservation work and study continue to this day.

About the Author

Charles Kightly is the author of the English Heritage Red Guide to Farleigh Hungerford Castle.

Find Out More

-

Description of Farleigh Hungerford Castle

Explore the different areas of Farleigh Hungerford Castle including the inner and outer courts, the chapel and the crypt.

-

Significance of Farleigh Hungerford Castle

More on the significance of Farleigh as an example of a late 14th-century quadrangular castle, and its notable association with the Hungerfords.

-

Research on Farleigh Hungerford Castle

Learn about the the research and documentation conducted on the history of the castle, from the 19th century to today.

-

Download a Plan of Farleigh Hungerford Castle

Download this PDF plan of Farleigh Hungerford Castle to see how the castle has developed over the centuries.

-

Download the Hungerford family tree

Download this PDF of the Hungerford family tree and learn how the different generations of Hungerfords were connected.

-

Sources for Farleigh Hungerford Castle

A summary of the main sources for our knowledge and understanding of Farleigh Hungerford Castle.

-

More Histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.