Significance of Farleigh Hungerford Castle

Farleigh Hungerford Castle is valued as an example of a late 14th-century quadrangular castle, and especially for its well-preserved chapel and contents. It is also notable for its association with the Hungerfords, many of whom played significant roles in national events between 1400 and 1700. The controversy that accompanied the castle's restoration in the 1920s was an important episode in the history of heritage conservation in England.

The Quadrangular Castle and Later Defences

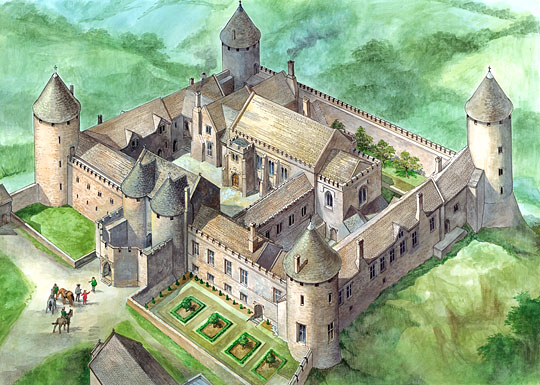

Farleigh Hungerford belongs to a small but distinctive group of castles – in reality fortified mansions rather than fortresses – built during the last three decades of the 14th century, mainly by men more or less closely associated with the court of Richard II (r.1377–99).[1] Several of these, such as Bolton (North Yorkshire) and Bodiam (East Sussex), were quadrangular, comprising four ranges of buildings around a central courtyard, with a tower at each corner.

This compact and innovative style of building, which allowed the inner faces of each range to be lit by large windows looking on to the courtyard while the outer faces remained defensibly sheer and almost windowless, represented a compromise between luxury and security. It dominated the last stages of castle-building in England, and influenced the undefended quadrangular mansions of the Tudor and Elizabethan periods.

At Farleigh Hungerford only two of the towers survive above foundation level, and the ranges between them are ruined. The hall range, rather than running along the north side, stood in the centre of the castle. But the castle's ground plan, together with early descriptions, proves that it belonged to this briefly fashionable group of castles.

With its four dissimilar and asymmetrically positioned towers, Farleigh is nevertheless far less regularly planned than some examples such as Bodiam and Bolton, or contemporary castles of other shapes, including the hexagonal Old Wardour (Wiltshire).

The south tower of the outer court, built between about 1430 and 1445, is a noteworthy survival from a period when comparatively few defences were built in southern England, especially since it was commissioned by Walter, 1st Lord Hungerford, who had much first-hand experience of besieging French fortresses.[2]

Chapel Monuments, Wall-paintings and Coffins

The chapel at Farleigh Hungerford[3] – much the best-preserved feature of the castle – is a comparatively unusual example of a free-standing private mortuary chapel developed over three centuries by a single family. It is especially notable for:

- the traces of 15th-century wall-paintings at the east end of the main chapel, mainly commissioned by Walter, 1st Lord Hungerford, in the 1440s. The large painting of St George, patron saint of England and of the Order of the Garter, has a now scarcely traceable figure of a knight wearing the Hungerford arms kneeling at his feet. It may well celebrate Walter's pride in his membership of the Order of the Garter.

- the series of family monuments, tracing developments in style from about 1400 (the fine effigial monument of the castle's founder, Sir Thomas, and Lady Joan Hungerford), via the more modest carved and painted Elizabethan and Jacobean tombs dating to between 1596 and 1613, to the grandiose marble monument of Sir Edward Hungerford III (d.1648) and his wife, Lady Margaret (d.1672).

- the very unusual survival of a complete mid-17th-century scheme of decoration in the north chapel, including wall- and ceiling paintings, chequered black-and-white marble paving, elaborate wrought-iron gates and windows, commissioned by Lady Margaret Hungerford between 1658 and 1665.[4]

- the family vault, with its eight anthropoid lead coffins of 16th- and 17th-century Hungerfords, four with moulded faces. Regarded as the best collection of this type of coffin in Britain, they are the only examples regularly on public view.[5]

Romantic Ruin to Conserved Monument

The castle is remarkable for the unusually large number of surviving paintings, sketches, prints, early photographs and other representations of its ruins and chapel, by both professional and amateur artists.[6]

Its identity as a 'romantic', ivy-clad and tree-grown – though crumbling – ruin was so firmly established that its restoration and conservation by the Ministry of Works from 1919 met with considerable and vociferous (but unsuccessful) opposition, at first from local antiquarians, and later in Country Life magazine and the Wiltshire Times.[7]

Farleigh and the Hungerfords

Farleigh Hungerford is also remarkable for being owned and developed by a single family throughout its three centuries of occupation.

Successive generations of Hungerfords played leading roles in many of the great events of English history from the late medieval to the later Stuart periods. They participated in the triumphs of Henry V; the Wars of the Roses; the vicissitudes of the Tudor period; the Civil Wars and Restoration; and the Exclusion Crisis (1679–81) of Charles II's reign, an attempt to exclude James, Duke of York (later James II), from the throne.

READ MORE ABOUT FARLEIGH HUNGERFORD CASTLE

Footnotes

1. C Kightly, Strongholds of the Realm (London, 1979), 134–5, 144–9.

2. C Kightly, 'Sir Walter Hungerford', in The History of Parliament: The House of Commons, 1386–1421 (Stroud, 1993), ed JS Roskell, L Clark and C Rawcliffe, vol 3, 446–53 (accessed 15 July 2014).

3. P Hughes, 'The chapel at Farleigh Hungerford Castle: building and repair, 1363–2003', unpublished English Heritage report (2003).

4. C Kightly, Farleigh Hungerford Castle (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2006; revised edn 2012), 13–15 (buy the guidebook).

5. C Moffett and R Hewlings, 'The anthropoid coffins at Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset', English Heritage Historical Review, 4 (2009), 54–71 (subscription required; accessed 2 July 2014); J Litten, 'The anthropoid coffin in England', English Heritage Historical Review, 4 (2009), 72–83 (subscription required; accessed 2 July 2014).

6. Listed in P Hughes, 'Farleigh Hungerford Castle: visual evidence, 1700–2000', unpublished English Heritage report (2001); Hughes, 'The chapel at Farleigh Hungerford Castle'.

7. Hughes, 'Farleigh Hungerford Castle: visual evidence'.