A Travelling Household

Countess Joan de Valence lived at Goodrich Castle for long periods after the death of her husband, William de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, in 1296. But Goodrich was by no means the only residence of the de Valence family. They owned property in more than a dozen counties, including a London townhouse. This was typical for a time when the monarch, nobles and bishops were almost constantly on the move. King Henry III, for example, moved up to 80 times in a typical year.

We know that between May 1296 and September 1297 – less than a year and a half – Joan stayed at 15 different residences. This meant that it wasn’t only the Countess who kept travelling between her different estates – her whole household was on the move. The servants and officials belonged to the family, not the house, and so they went wherever the head of the household went. In all, the Countess’s household varied between 122 and 196 people.

The people of Goodrich Castle

In 1296 Countess Joan spent several months at Goodrich Castle with her daughter-in-law Béatrice and a household of around 120 servants. We know the names of many of them from the surviving castle accounts. Select the images below to find out more about them. (All images by Ilaria Urbaniti © English Heritage)

Entertaining at Goodrich Castle

Large numbers of people had to be fed in a medieval household. In fact Joan de Valence spent 40% of her income on food and drink. When she arrived at Goodrich Castle in November 1296, 81 pigs were killed and countless loaves of bread were baked to prepare for her stay.

The Countess was often joined by her daughter Isabel, her son Aymer and his first wife, Béatrice, and eminent guests and friends. They included the young Gilbert de Clare and his household, the lady of Raglan Castle and the prioress of Aconbury.

The setting for feasts and other large gatherings of the household and guests would have been the great hall, the focal point of the castle. Eating in public was part of the everyday life of a great household, and etiquette had to be meticulously observed. This included the seating arrangements. At the high table – at the end of the hall furthest from the kitchen – sat the host or hosts, with the most important guests. Then came the other members of the household, seated at long tables with benches in descending order of status.

There were two main meals a day, and they weren’t eaten quickly. Lunch, taken around 10 or 11 in the morning, typically lasted two to three hours, with supper after vespers (evening prayers). Both meals together could take up to six hours.

A feast fit for a Countess

Countess Joan’s accounts for 1297 reveal that the kitchen could produce meals of enormous size. On Easter Sunday that year the household at Goodrich celebrated the end of the fasting season of Lent with:

3 quarters of beef and 1½ bacons, 1½ unsalted pigs, half a boar, half a salmon, all from the castle's store, half a carcass of beef costing 10 shillings, mutton at 15 pence, 9 kids at 3s 8d, 17 capons and hens at 2s 7d, 2 veal calves at 2s 6d, 600 eggs at 2 shillings, pigeons at 2 pence with 24 other pigeons from stores in Shrivenham, cheese at 4 pence and a halfpenny for transport by the boat, all told, 22s 6d halfpenny.

Image: The high table of a hall in the mid-14th century, from the Luttrell Psalter. Countess Joan’s accounts describe similar scenes of the Countess dining with her family and important visitors (© British Library Board. All rights reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Accommodating the Household

As well as Countess Joan’s travelling household of up to 200 people and frequent guests, there was also a staff permanently based at Goodrich under the command of the constable, who maintained the castle’s security. At the bottom of the hierarchy were 20 poor people, who depended on the Countess’s charity.

How could so many people be housed at once in the relatively small castle at Goodrich? Working out who stayed where involves examining the ruins and the medieval documents, comparison with other sites, and ultimately guesswork.

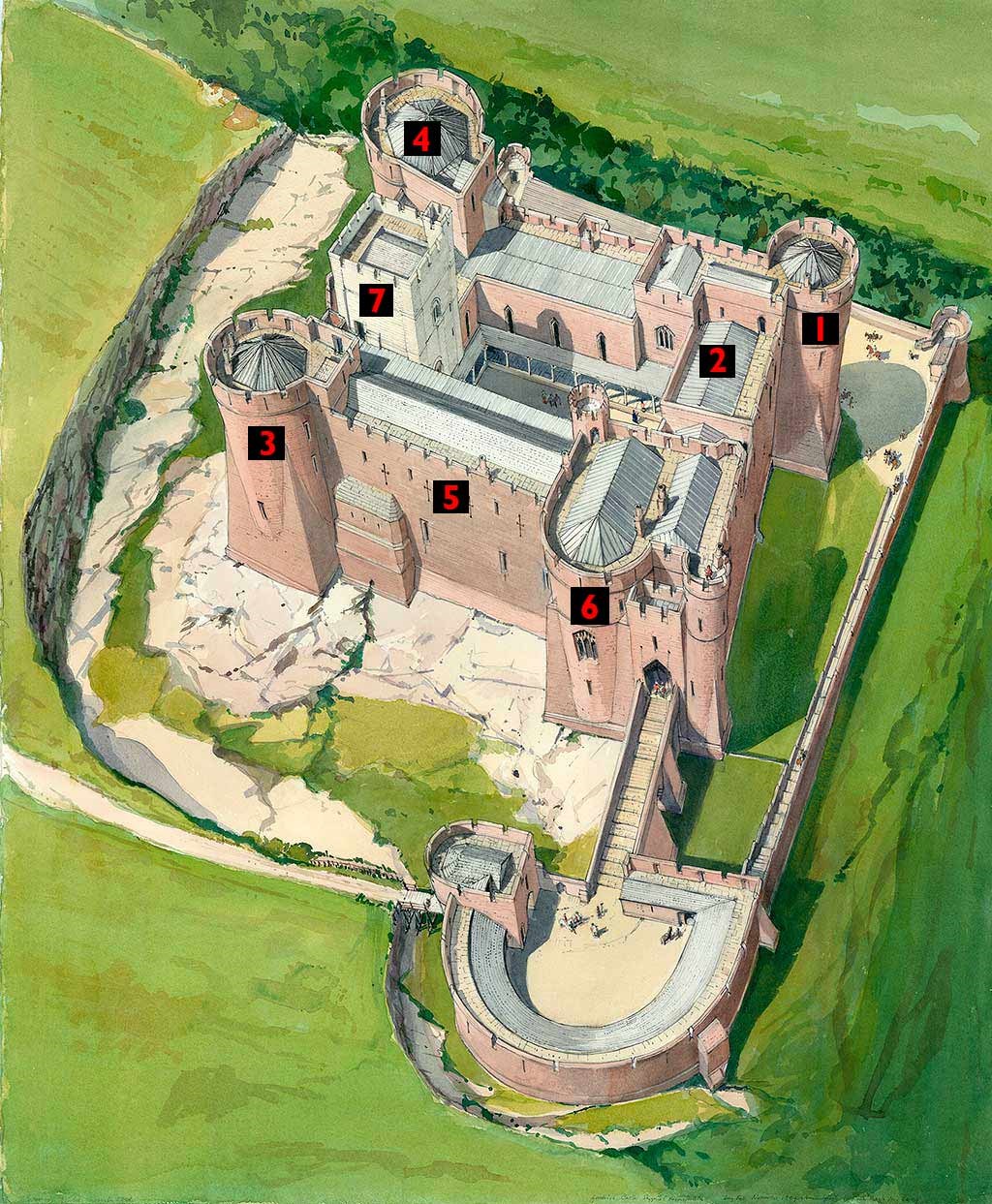

Many of the rooms around the courtyard and in the towers have fireplaces, window seats, washbasins and latrines – signs that they were meant to be lived in. At many medieval castles, the most important rooms lay beyond the end of the great hall, furthest from the kitchen. At Goodrich this would be the north-west tower and north range (marked 1 and 2 on the illustration), which almost certainly contained the bedchambers and solar, or great chamber, of Countess Joan and William de Valence.

More well-appointed rooms for family members and guests lie on two floors of the south-east tower (3) and the top floor of the south-west tower (4).

Other buildings, including the east range (5), the rooms over the gatehouse (6) and perhaps the keep (7), were probably used by household officers, soldiers and servants.

Even this extensive accommodation, however, wouldn’t have been enough for the full household. Some of the retinue would probably have had to stay in the nearby village, or in wooden structures and tents outside the castle walls.

Reconstruction drawing by Terry Ball (© Historic England)

Find out more

-

History of Goodrich Castle

Read a full history of Goodrich Castle, one of the best-preserved medieval castles in England, which was besieged and captured by Parliamentarians during the Civil War of the 17th century.

-

The Siege of Goodrich Castle

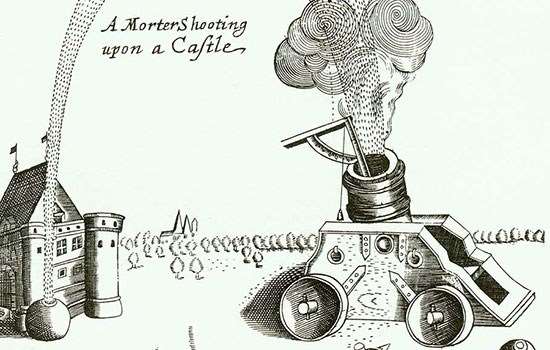

In 1646 Goodrich Castle was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the English Civil War, which Parliament finally won with the aid of a huge mortar, known as Roaring Meg.

-

Life under siege at Goodrich Castle

The 17th-century objects found at Goodrich Castle help us to imagine what life at the castle was like during the Civil War siege. View some of them in detail here.

-

English medieval castles

Once symbols of power and prestige, England’s medieval castles are now monuments to centuries of history. Discover the stories held within their walls.