The Formation of Flint

The flint here was originally formed 90 million years ago, when the area of Grime’s Graves was a warm sea with a coral reef. Millions of tiny marine creatures and sponges sunk to the sea bed when they died, eventually creating layers of chalk and silica (flint).

The third layer of flint at Grime’s Graves – known as ‘floorstone’ – was highly valued in prehistory for its excellent quality and glossy black colour. Unlike flint found on the surface, the mined flint was nearly flawless and could be worked (or ‘knapped’) predictably. In modern times, flint from the nearby Brandon area was favoured by the gunflint industry for use in firearms.

The Neolithic Period

The Neolithic period (about 4000–2300 BC) was a time of great social and technological change in Britain. Farming was introduced by migrants from the Continent about 4100 BC, along with pottery and the extraction of stone from hard-to-reach locations in order to create new types of stone artefact. The communal effort needed to dig deep mineshafts and galleries, such as those seen at Grime’s Graves, would have been as monumental as erecting the stone circles at Stonehenge and Avebury.

Around 2600 BC, during the late Neolithic, people discovered and started mining the rich, dark flint at Grime’s Graves. Flint was a valuable commodity used to make all kinds of tools: arrowheads for hunting and weaponry; axes for tree-felling; and cutting, scraping and piercing instruments for preparing hides, processing plant fibres and shaping wood. Trade networks were extensive, and the fine black flint from Grime’s Graves was exchanged or traded over long distances.

At Grime’s Graves, the miners dug shafts up to 13 metres (about 43 ft) deep to where the best flint lay. They worked in subterranean galleries at the base of each shaft, prising out the flint using picks made from antlers. Although the earthworks visible today represent 433 mines and pits, excavations and recent geophysical surveys suggest that the mines covered a much greater area.

Rituals in the Mines

Artefacts found in pits at Grime’s Graves may be evidence of ceremonial activities or deliberate offerings. For the miners, rituals may have been part of everyday life.

In 1971 two highly decorated Grooved Ware pots were discovered on a raised chalk platform at the base of a shaft. The excavation of a pit known as Pit 15 produced seven antler picks on another platform, and many mines contained chalk carvings of cups, balls, phalli and other objects. In a gallery leading from Greenwell’s Pit (the deepest pit excavated at Grime’s Graves) a dog skeleton, which had been carefully buried, was discovered. Hearths were found on many shaft floors. These had not been used for lighting or cooking, but instead may have had ritual functions.

Even after they had been abandoned, the shafts were a focus for special events. Fires were lit periodically, and offerings of animal remains and occasionally human bones were placed in the shaft fills. These deposits may have been part of closing or renewal rituals.

Read more about the rituals at Grime’s GravesThe Bronze Age

The appearance of the first metal objects in about 2400 BC heralded the arrival of a new technology, and the beginning of the Bronze Age (about 2300–800 BC). Mining continued at Grime’s Graves until about 2100 BC. After a gap of around half a millennium, flint mining briefly resumed again in simple pits, indicating that flint remained an important resource well into the Bronze Age.

Mining probably eventually ceased as bronze metalwork eclipsed traditional flint tools. From around 1400 BC, the mineshafts were used as large waste dumps (middens). Evidence of textile production, leatherworking and woodworking was discovered alongside the bones of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses and deer and remains of wheat and barley. This suggests that a settlement was established at Grime’s Graves for the first time, although no evidence of houses has been found.

The middens also contained more than 8,000 fragments of pottery, evidence for metalworking, and 6 tonnes of worked flint (recycled from earlier waste dumps, rather than mined). Significantly, large clay moulds for casting ceremonial spearheads were found, indicating that important bronze working was happening on site. Many of these large spearheads were found deposited in the Fens – a large area of marshland in the east of England – showing possible regional connections.

Iron Age Activity

There is little evidence for settlement at Grime’s Graves during the Iron Age (about 800 BC–AD 43), but the site was used as a small burial ground between about 390 and 150 BC. This practice followed a regional tradition of reusing existing hollows and pits as graves.

The two most significant burials were discovered in the upper levels of a shaft excavated in 1971. The first was of a young adult woman with a decorated chalk plaque by her hip. This was later disturbed by the burial of an adult male with a necklace (or earrings) comprising two iron beads.

Both burials appear to have been accompanied by ceremonies at which fires were lit and offerings placed beside the bodies. It is possible that other undated skeletons previously found in the upper levels of shafts may also be from the Iron Age.

Roman and Medieval Periods

During the 1st to late 4th centuries AD Roman visitors left behind pottery sherds from vessels manufactured in Gaul (now France), Spain, Oxfordshire, the lower Nene valley (near Peterborough) and probably East Anglia.

The name Grime’s Graves is Anglo-Saxon in origin, as is that of Grimshoe mound on the eastern side of the site. The Anglo-Saxons believed that the landscape was the work of the Saxon god Grim (or Woden), a god of the hunt. ‘Grimshoe’ is a corruption of ‘Grim’s Howe’ or ‘Grim’s burial mound’ and ‘Graves’ (meaning hollows or earthworks) was used to describe the surrounding landscape.

Grim was claimed by the local Anglo-Saxon kings as an ancestor, a claim legitimised by the god’s burial on their land. From around 939 the mound became the meeting place of the local hundred, a group of 16 parishes, who came here to settle disputes.

Domesday Book (1086) records that the Breckland (the heathland area of Norfolk in which Grime’s Graves lies) was the least populated area of East Anglia. From the 12th century onwards manorial lords established rabbit warrens as a practical response to the poor soils, which were inadequate for cereal farming, and the shortage of peasants to work the land. From 1224 Grime’s Graves was owned by nearby Broomhill Priory and was probably also used as a warren.

Read more about medieval rabbit warrensInvestigating Grime’s Graves

Grime’s Graves is the largest and best excavated flint mine in the country. Research here has helped us to understand how Neolithic people worked and used the mines.

The first reference to Grime’s Graves as a place of antiquarian interest was in Edmund Gibson’s additions to William Camden’s Britannia (1695), where the site was described as ‘a hill with certain small trenches … call’d Gimes-graves’. In 1761 John Parker produced a map depicting the site as 25 circles, with an additional circle for Grimshoe mound. The Ordnance Survey mapped the site in 1824 as a series of hollows on a low spur. This was followed by the earliest known sketch of the site, made by the Revd Francis Vyvyan Luke in 1852 (see Sources for Grime’s Graves).

The earliest recorded excavations took place in 1852, when the Revds ST Pettigrew and CR Manning dug several pits. But it was not until 1868–70, when notable Victorian antiquarian and archaeologist Canon William Greenwell excavated a deep shaft, that Grime’s Graves was proved to be a Neolithic flint mine – the first to be recognised as such in Britain. Digging deeper than earlier archaeologists, Greenwell revealed the true depth of the mines, the tools the miners used, and that the mineshafts had galleries radiating from the base. His discovery of a greenstone axehead allowed Greenwell to date the mine to the Neolithic period. The pit that Greenwell excavated is now known as ‘Greenwell’s Pit’ and is the oldest, deepest and best preserved pit to have ever been excavated so far.

Explore a virtual tour of Greenwell’s PitOver 30 pits have been excavated at Grime’s Graves. Further excavations took place in 1914 at Pits 1 and 2, and at others during the interwar years, culminating with Pit 15 in 1939 by Leslie Armstrong, where he claimed that the ‘Chalk Goddess’ – a mysterious chalk figurine resembling a woman – was discovered. The most recent campaign of excavations was during the 1970s, first by Roger Mercer on behalf of the Department of the Environment, and then by the British Museum.

In 1931 Grime’s Graves became a guardianship monument under the protection of the Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings. Set amid the distinctive Breckland heath landscape, Grime’s Graves is also a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). The combination of chalk soils, sandy heath and acid grassland supports a wide range of rare plants and wildlife.

By Peter Topping and Jennifer Wexler

Read more about Discoveries at Grime’s GravesExplore More

-

Grimes Graves Audio Guide

In this audio tour of the site archaeologist Phil Harding and English Heritage historian Dr Jennifer Wexler explore the lunar-like landscape of Grime’s Graves.

-

Virtual Tour

Explore this 360° virtual tour of Greenwell’s Pit, the oldest, deepest and best-preserved pit excavated so far at at Grime’s Graves.

-

A Chalk Goddess: Real or Fake?

Many questions have been raised about the authenticity of a figurine discovered at Grime’s Graves in 1939. We explore this intriguing object and learn more about the mysteries that surround its origin.

-

Collection Discoveries

Discover some of the objects found at Grime’s Graves including a range of skilfully worked (or ‘knapped’) tools, demonstrating the many uses and importance of flint during prehistory.

-

Ritual Mysteries

Intriguing finds from many of the pits at Grime’s Graves suggest that mysterious rituals accompanied the everyday task of mining. Read more about these discoveries here.

-

Research on Grime’s Graves

Read about some of the research that has taken place at Grime’s Graves, from antiquarian discoveries up until today.

-

Sources for Grime’s Graves

Read this guide to the main sources for our knowledge and understanding of the late Neolithic flint mines at Grime's Graves.

-

Description of Grime’s Graves

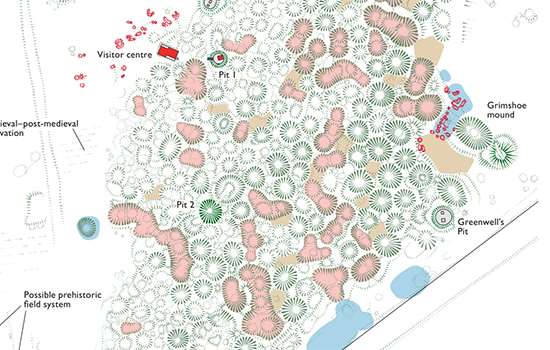

Read a description of Grime’s Graves – the dips and humps of the earthworks here represent the visible remains of 433 Neolithic mines and pits.

-

Download a plan of Grime’s Graves

Download this pdf aerial plan of the site to learn more about how the site has developed over time.