Pioneers of industry

The world’s first iron bridge emerged during a time of immense change in Britain – it was the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. New technologies were being developed and the country’s rural landscape was changing as an industrial nation began to take shape.

One such development took place in 1709, in the Shropshire village of Coalbrookdale. Abraham Darby (1678–1717) – the first in what would become a distinguished dynasty of iron masters – had pioneered an innovative method of iron smelting.

Using coke made from local coal to fuel furnaces rather than charcoal, Darby’s discovery made the mass production of cast iron economically viable.

With this breakthrough in production, the iron trade in Britain accelerated and local industry began to flourish.

A bold idea

One of the boldest attempts with a new material was the application of cast iron to bridges (Thomas Tedgold, English engineer and author, 1824)

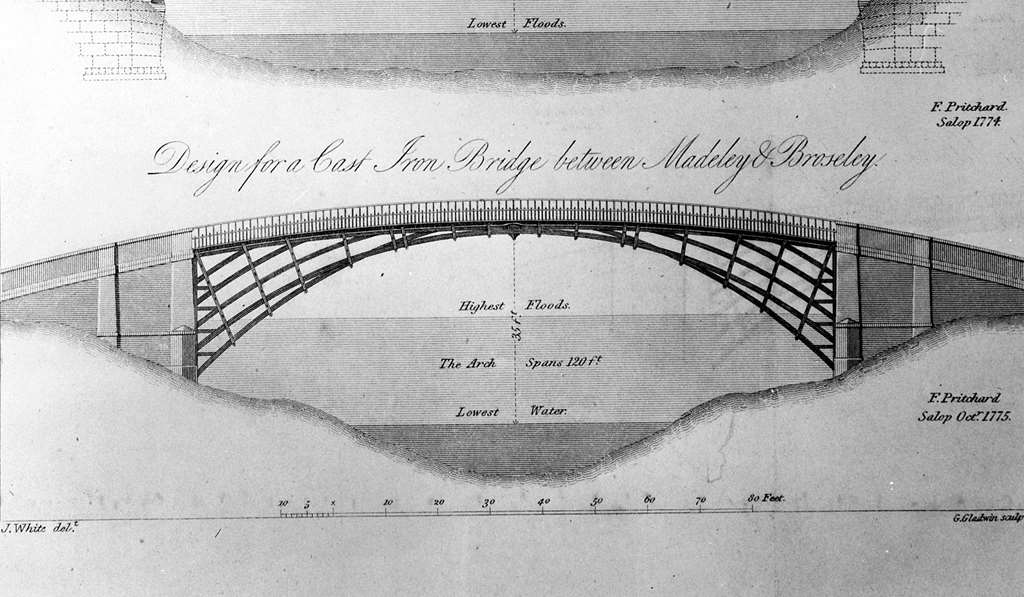

As industry around the gorge grew, so did the need for a strong and durable bridge to transport goods across the river. In 1773, Thomas Farnolls Pritchard – an architect from Shrewsbury – had a bold idea. Combining engineering expertise and new iron-casting techniques, he proposed the world’s first iron bridge, which would link the parishes of Madley and Benthall over what was one of the busiest rivers in the country.

Pritchard’s designs were approved by Act of Parliament and in 1777 construction began. Overseen by Darby’s grandson Abraham Darby III after Pritchard’s death, it was to be a cast iron single-span bridge of 30 metres, with five main semicircular ribs.

The radical new structure, which formally opened on New Year’s Day 1781, used a total of 378 tons of iron at a cost of around £6,000 – significantly more than the £3,200 first estimated.

See our Iron Bridge infographic

The Impact of the bridge

It must be the admiration, as it is one of the wonders, of the world. (John Byng, traveller and writer, 1784)

The fusion of natural beauty and industrial activity around the Severn Gorge attracted many artists and writers. Richard Warner, a writer and priest, described Coalbrookdale in 1801 as ‘a scene in which the beauties of nature and processes of art are blended together in curious combination’.

But the unveiling of the Iron Bridge brought new visitors, who marvelled at its scale and ingenuity. The bridge became a centre of commerce and a town known as Ironbridge grew up around it.

The structure also inspired the future of bridge design and engineering. Its massive strength saw it survive the great flood of 1795, motivating builders and engineers like Thomas Telford to construct their own iron structures.

A curious construction

It is one arch, a hundred feet broad, fifty-two high, and eighteen wide; all of cast-iron, weighing many hundred tons. I doubt whether the Colossus at Rhodes weighed much more. (John Wesley, Anglican cleric and theologian, 1779)

Although Darby commissioned many paintings and engravings of the finished bridge, a lack of images or eyewitness accounts meant that, for over 200 years, little was known of exactly how Darby managed to erect this structure of almost 400 tons.

But in 1997 a small watercolour sketch by Elias Martin, which illustrated the building of the bridge, was discovered in a Stockholm museum. This exciting find, along with recent research, revealed much about the building process.

While Darby’s accounts suggest the use of scaffold poles, timber and rope during construction, Martin’s painting shows a wooden framework used to raise the half-ribs from the deck of a vessel.

Research also revealed that 70% of the components of the bridge – including all the large castings – were made individually to fit, and all differ slightly from one another as a result. Darby’s workers employed joining techniques used in carpentry, such as dovetail and shouldered joints, adapting them for cast iron.

Engineering the Iron Bridge

We visited Blists Hill, near to the Iron Bridge, to see the original iron casting process that would have been used to create the bridge components in action. Watch more to see a miniature bridge section being cast and learn what makes the bridge so strong.

The Future of the Iron Bridge

The bridge remained in full use for over 150 years, by ever-increasing traffic. But in 1934 it was finally closed to vehicles and was designated an Ancient Monument.

Since then, massive works to strengthen the bridge have been undertaken. In 1973, for example, a reinforced concrete strut was built across the bed of the river to brace the two abutments.

In 1999–2000 English Heritage, together with the Ironbridge Gorge Museums Trust, carried out a full archaeological survey, record and analysis of the bridge. The three-dimensional digital record now enables detailed understanding and management of the structure.

In 2018, English Heritage completed a major conservation project to repair the Iron Bridge. It had been suffering due to stresses in the ironwork dating from the original construction, ground movement over the centuries and an earthquake at the end of the 19th century. The bridge now stands as testament to this large-scale work, for future generations to enjoy.

Read more about the projectIron Bridge Timeline

1709Coal Territory

Abraham Darby, a former brass founder, discovered that coal from Coalbrookdale could be used to smelt iron. This enabled the economically viable mass production of cast iron. Kickstarting the Industrial Revolution, the foundry was producing large quantities of cast iron goods within a couple of years.

1773Pritchard's Wild Idea

Shrewsbury architect Thomas Pritchard had a bold idea. Capitalising on engineering expertise and new iron-casting techniques, he proposed the world's first iron bridge, to be cast and built by Abraham Darby's grandson, Abraham Darby III. A strong and durable bridge, it would support the transportation of goods across the River Severn and cut down barge traffic.