The 17th-Century House

The first house on the site was probably a brick structure built by John Bill, King James I’s printer, who bought the estate in 1616.[1] His son and grandson owned it until 1690, when it was sold to Brook Bridges for £3,400.[2]

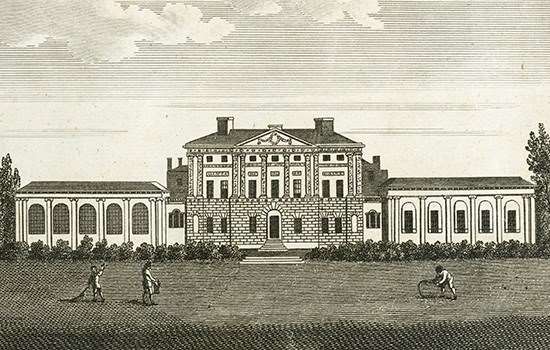

The house, which was already substantial (24 hearths were recorded in the 1665 Hearth Tax assessment),[3] was significantly modified in about 1700, possibly by Brook Bridges’s son, William, who owned Kenwood from 1694 to 1705. The new house was a two-storey red brick building with stone quoins, large sash windows, a hipped roof and a projecting central section with a triangular pediment.

The Early 18th Century

Kenwood changed hands several times in the 18th century. From 1704 to 1711 it belonged to a London merchant, John Walter, and then to William, 4th Earl of Berkeley. He sold it to John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll, in 1712.

In 1746 the Scottish aristocrat John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, acquired Kenwood. His interest in plants probably led to the addition of the orangery to the west of the south front and the introduction of new species to the grounds. His mother-in-law, the well-travelled Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wrote to her daughter in 1749:

I very well remember Caenwood House … I do not question Lord Bute’s good taste in the improvements round it, or yours in the choice of furniture.[4]

The footprint of this house first appears on John Rocque’s plan of Westminster and Southwark of 1746,[5] and Mary Delany’s drawing of 17 June 1756 (above) shows it as a ‘double pile’ house painted white, with a steeply pitched roof and dormer windows.

Home of Lord Mansfield

In 1754 William Murray (1705–93), from 1756 Lord Chief Justice, acquired Kenwood for £4,000. He and his wife, Elizabeth (Betty), née Finch (1704–84), used it as their weekend country villa. Lord Mansfield expanded the estate, and soon swept away Bute’s formal gardens. Some of the fishponds were merged to become Wood Pond and the Thousand Pound Pond was created, its name presumably reflecting the exorbitant cost of its creation.

Lady Mansfield wrote to her nephew in May 1757:

Kenwood is now in great beauty. Your uncle is passionately fond of it. We go thither every Saturday and return on Mondays but I live in hopes we shall now soon go thither to fix for the Summer.[6]

The couple were childless, but from about 1766 they agreed to accommodate their niece, Anne Murray, and two great-nieces, Elizabeth Murray and Dido Elizabeth Belle. Dido was the illegitimate daughter of a formerly enslaved young black woman named Maria Bell and Mansfield's nephew Sir John Lindsay. It was extremely unusual at this time for a mixed-race child to be raised not as a servant, but as part of an aristocratic British family

The decision to house the girls permanently at Kenwood, combined with Mansfield’s increasing status and wealth – in 1776 he was created 1st Earl of Mansfield – encouraged him to commission the Scottish neoclassical architect Robert Adam and his brother James to remodel the house from 1764 to 1779.

Find more about Dido BelleRobert Adam’s Remodelling

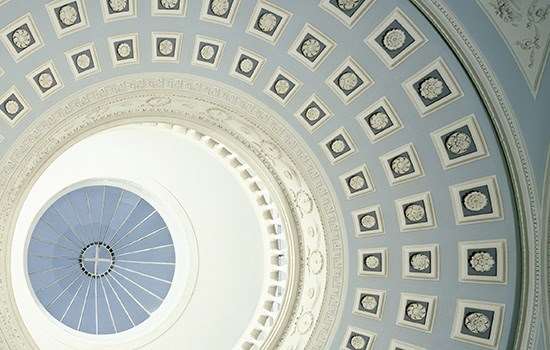

Robert Adam’s changes included the addition of a new entrance on the north front in 1764, which created the existing full-height giant pedimented portico. He originally designed the south front elevation in 1764, but changed it in 1768 in order to insert attic-storey bedrooms.

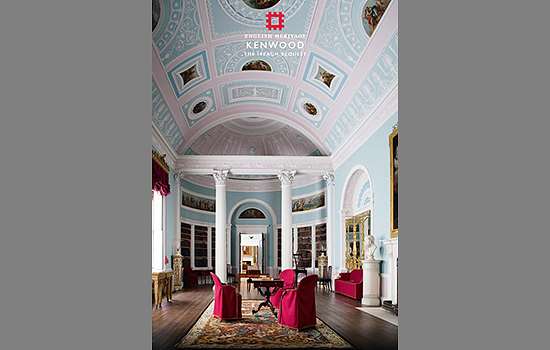

Adam also modernised the existing interiors, notably the entrance hall (1773), Great Stairs and antechamber, and built a new ‘Great Room’ or library (1767–9) for entertaining. The ground-floor rooms on the south front all received Adam’s new decorative schemes. These social spaces for the family included a drawing room, parlour and ‘My Lord’s Dressing Room’.

The extent of Adam’s alterations on the first floor is difficult to assess as no original floor plan survives, but he certainly produced new schemes for Lord and Lady Mansfield’s bedchambers and designed the chinoiserie chimneypiece, which survives in the upper hall. Adam claimed that Lord Mansfield ‘gave full scope to my ideas’ when he published plans of Kenwood in 1774.[7]

Download a plan of KenwoodKenwood after Adam

In 1793 Mansfield’s nephew, David Murray, Viscount Stormont (1727–96), succeeded to the earldom and quickly began to make significant changes. His first step was to have a new road built, diverting Hampstead Lane away from the forecourt, to provide the house with more privacy.

Soon afterwards the 2nd Earl commissioned the little-known architect George Saunders to build the north-east and north-west wings, providing Kenwood with an elegant dining room and music room. Saunders also added a service wing with kitchens, bedrooms, a brewhouse and a laundry, partially hidden behind the north-east wing. At the same time the 2nd Earl built new gate lodges, a new farm and stables, and a dairy, which was designed by Saunders for Louisa, 2nd Countess of Mansfield.

The 2nd Earl also employed the celebrated landscape gardener Humphry Repton to remodel the grounds at Kenwood. Repton created a series of meandering paths around the estate to show off all its aspects to their best advantage. He broke up the wide sweeping views in the parkland by planting groves of trees for variety and contrast. A walled forecourt was removed, creating a Half Moon Lawn in front of the house to show off its elegant frontage. He also converted the kitchen garden to the west of the house into an intricate flower garden. The gardens and parkland known to Repton and his patron survive in large part today.

Kenwood in the 19th Century

David William Murray, 3rd Earl of Mansfield (1777–1840), inherited Kenwood from his father at the age of 19. In 1815 he appointed his architect, William Atkinson (1775–1839), to make alterations and eradicate dry rot. The work involved extensive redecoration, the addition of second-floor rooms to the service wing and the installation of bookcases in the mirrored niches in the library.

During the 19th century the Mansfields preferred to live at their Scottish estate, Scone Palace. The 4th Earl, William David Murray (1806–98), however, spent three months of the year at Kenwood and was responsible for the insertion of large French windows in the music room.

Kenwood from the 20th Century

The 6th Earl of Mansfield, Alan David Murray (1864–1935), inherited Kenwood from his brother in 1906, but decided to sell it in 1914. From 1909 it had been rented out to tenants, including Grand Duke Michael Michaelovitch (1861–1929), second cousin to the last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, and his family, who lived there until 1917. They were followed by the American millionairess Nancy Leeds, who moved out when she married Prince Christopher of Greece in 1920.

In November 1922 Lord Mansfield sold off the contents of the house, including some of the original furnishings, in a four-day sale. By 1925, however, Kenwood’s future was secured when Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh (1847–1927), bought the house and 74 acres immediately surrounding it. The Kenwood Preservation Council purchased land including the ponds and ‘Ken Wood’, and vested it in London County Council.

The Iveagh Bequest Act of 1929 stipulated that Kenwood should be open free of charge to the public with the ‘mansion and its contents … preserved as a fine example of the artistic home of a gentleman of the eighteenth century’,[8] including the display of 63 of Lord Iveagh’s outstanding collection of Old Master and British paintings.

Repair and Conservation

During the Second World War Kenwood housed servicemen. In 1949, realising the need for significant repair work, the Iveagh Bequest Trustees handed it over to London County Council. It was taken over by English Heritage in 1986.

Following an extensive repair and conservation project begun in 2012, part-funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, Kenwood reopened in late 2013. Work included repairing the Westmorland slate roof and redecorating the exterior and interior of the house, based on new paint research on the original Adam scheme, and a redisplay of the Iveagh Bequest paintings in the south front rooms.

About the Author

Dr Susan Jenkins was formerly a senior curator of collections at English Heritage, and is the co-author (with Laura Houliston) of the guidebook to Kenwood.

More about Kenwood

-

VISIT KENWOOD

Kenwood’s breathtaking interiors, world-class art collection and glorious parkland are free for everyone to enjoy.

-

KENWOOD COLLECTION HIGHLIGHTS

Explore highlights from the collection, including paintings by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Dyck and Turner.

-

Why does Kenwood matter?

Learn why Kenwood’s architecture and interiors, as well as its collections, are considered so significant.

-

Description of Kenwood

Discover more about the architecture of Kenwood House, designed by Robert Adam.

-

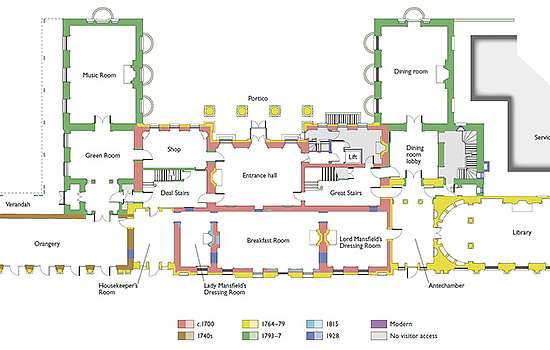

Download a plan of Kenwood

Download these floor plans to explore in detail how the villa at Kenwood has been altered over time.

-

Research on Kenwood House

Learn how we know so much about Kenwood House and where we still have gaps in our knowledge.

-

Sources for Kenwood

Use this summary of primary and secondary sources to find out more about Kenwood’s history.

-

Buy the Guidebook

Learn more about Kenwood’s history with the official guidebook, which also includes a full tour of the house.