PORTRAIT MINIATURES: THE DRAPER GIFT

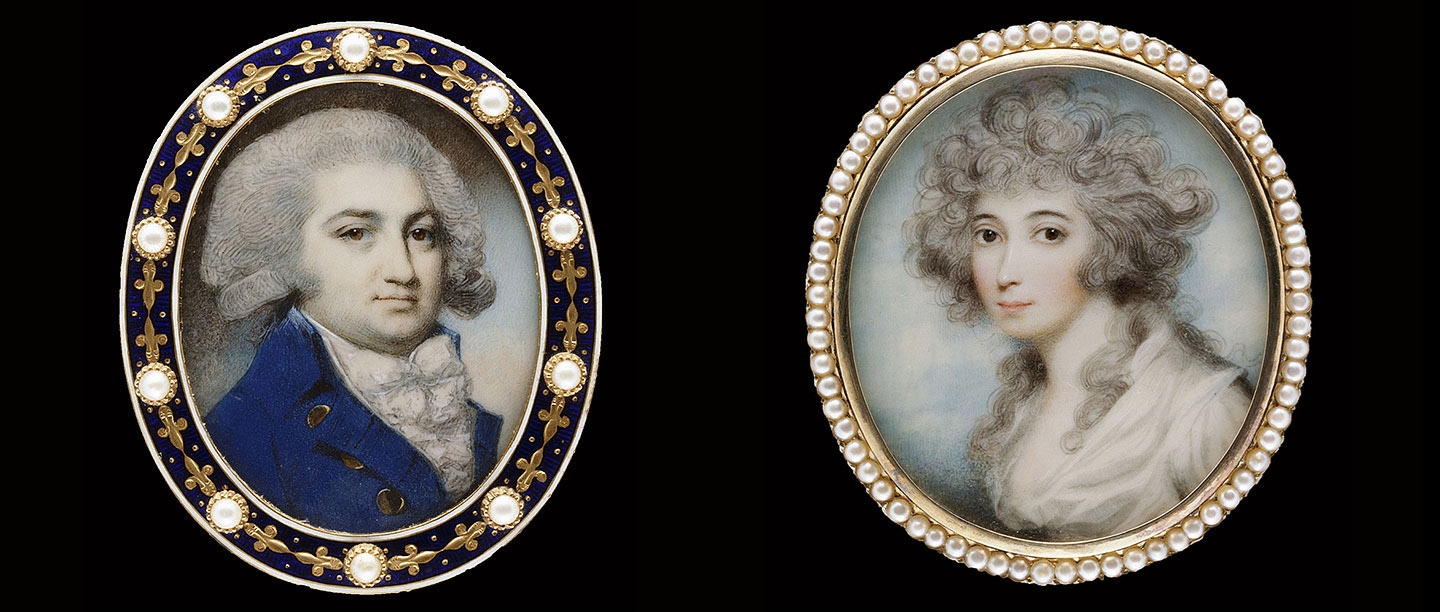

This small but significant collection has at its core a gift of 20 miniatures bequeathed in 1988 by Marie Elizabeth Jane Irving Draper, a Hampstead resident who loved Kenwood. Long fascinated by 18th-century portraiture, Marie began collecting miniatures in the 1970s after developing glaucoma, as their size and portability allowed her to see them clearly.

Marie’s original bequest comprised miniatures painted in Britain in the mid to late 18th century and included works by many of the foremost artists of the period. The gift inspired both Marie’s mother, in her role as executor, and the curators at English Heritage, and in the decade following Marie’s death the collection of miniatures at Kenwood grew through acquisitions financed from her estate.

Today, this collection of more than 120 portrait miniatures is known as the Draper Gift and traces the development of the miniature in Britain over the course of the 18th century.

THE PORTRAIT MINIATURE’S HEYDAY

Miniatures painted in watercolour on vellum (calf-skin) were first introduced into England at the court of Henry VIII (r.1509–47) and flourished for two centuries at the hands of artists like Nicholas Hilliard, Isaac Oliver and Samuel Cooper. But at the beginning of the 18th century, miniature painting was revolutionised when a new technique arrived from Italy: watercolour on ivory. For the next half century, miniaturists experimented with new techniques for painting on this oily, unabsorbent surface.

The work of artists like Samuel Collins, Penelope Cawardine and Luke Sullivan tended to be small (1–2 inches high) and painted with an unpretentious naturalism, leading them to be posthumously christened ‘The Modest School’. These miniaturists were so successful in overcoming the challenges of painting in watercolour on ivory that by the middle of the 18th century a new, distinctly national style had been established, paving the way for the bravura of the next generation.

The reigns of George III (1760–1820) and George IV (1820–30) were the heyday of the portrait miniature in Britain. In the 1760s a new generation of artists emerged who elevated the portrait miniature to new heights. Miniaturists including Jeremiah Meyer, Richard Cosway, John Smart and later George Engleheart painted on a larger scale (often over 3 inches), and developed styles and techniques that better exploited the luminous qualities of ivory.

Such miniaturists were not only leaders in their field but ranked alongside artists like Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Romney as the greatest portraitists of the age. Alongside them were many other able miniature painters, each with their individual style. In 1760, those looking to commission a miniature could choose from around two dozen artists; by the close of the century that number had grown to more than 60, with some miniaturists painting more than 100 works a year.

An intimate role

The intimate scale of portrait miniatures meant that they had always been appreciated as objects of personal adornment and private sentiment. In a time before photography, they were the only easily portable likenesses of friends or family. In the 18th century, they were often decoratively mounted as pendants, bracelets and brooches or set into snuff boxes.

The intimate and deeply sentimental role portrait miniatures could occupy is encapsulated in an inventory made in 1840 by Frederica, 3rd Countess of Mansfield. Listing the contents of her bedroom at Kenwood, she records a miniature of her eldest daughter, also named Frederica, who died in childbirth aged 23, and of her son-in-law, Colonel James Stanhope, who took his own life at Kenwood two years after his wife’s death. The record of the miniatures, written in the countess’s own hand, describes how they are ‘sealed in my drawer under lock and key’. Clearly they were treasured tokens of lost loved ones.

JEWELLERY: THE HULL GRUNDY COLLECTION

‘If you don’t fall in love, don’t buy it’ was the motto that guided Anne Hull Grundy over a lifetime of collecting. Born into a Jewish banking and industrial family in Nuremberg in 1926, Anne Hull Grundy, née Ullmann, fled Germany for England with her family when the Nazis rose to power in 1933. The family settled in Northampton, where her father Philip Ullmann’s company – Mettoy – became famous for its metal toys, including Corgi cars.

Her family’s wealth, together with income from the Keyser Ullman bank, enabled Anne to begin collecting jewellery at the age of 11. It was to become a lifelong passion after she was struck down with a debilitating respiratory condition shortly after her marriage to artist and entomologist John Hull Grundy. The condition confined Anne first to a wheelchair and ultimately to bed. Buying many of her treasures by post, she assembled one of the finest jewellery collections in the world.

Kenwood is one of no fewer than 70 collections to benefit from Anne Hull Grundy’s generosity. With each gift, she specifically selected objects to complement the museum’s existing collection. Her gift to Kenwood, made in 1975, comprises a fine collection of Georgian, Regency and Victorian costume jewellery, with a focus on what Anne described as ‘a dazzling display of Georgian splendour’.

All that glitters

Most of the pieces in the Hull Grundy Collection at Kenwood can be described as ‘costume jewellery’, as they use semi-precious or replica stones and metal alloys rather than gold and diamonds. However, like all Georgian jewellery, they are meticulously handcrafted. Georgian jewellery makers were highly trained artisans, skilled in all areas of design and craftsmanship.

Silver, gold and Pinchbeck – an alloy of copper and zinc created to resemble gold – were popularly used in Georgian jewellery-making. Cut-steel and iron jewellery also became fashionable after France and Germany appealed for donations of precious jewellery to the national cause during the Seven Years War (1756–63) and the War of Liberation (1813). In return, donors received jewellery made from iron and cut steel.

Diamonds became hugely fashionable around the beginning of the 18th century, particularly for evening wear. Other gemstones like garnets, rubies and emeralds were popular for day wear, together with coral, ivory, pearls, shell and even human hair.

Equally fashionable among all classes were imitation gems. Paste – a compound of glass – was originally developed in France in the 17th century. By the mid 18th century it had become popular throughout Europe, not only as a substitute for diamonds but in its own right. Pastes were often more versatile than the gems they imitated, as they could be more easily cut and fitted. This was especially advantageous for the 18th-century jeweller, as designs of the period favoured close set stones, with little metal visible between. The craftsmanship of these ‘fake’ jewels reached such heights that paste was even worn at the royal court.

From day to night

During the day, middle- and upper-class women wore a range of jewellery, which could include a cameo or lace pin, a necklace or chain with a watch, small coloured stone rings, matching bracelets (worn in pairs on each wrist) and earrings. A chatelaine – a chain from which essential daily items were suspended – was the most important item of daytime jewellery. Carrying items including scissors, needle cases and scent bottles, a chatelaine acted rather like a modern handbag.

For evening wear, the rivière (river of light) necklace was fashionable, forming a shimmering circle around the neck. The effect was enhanced by cascading chandelier-style earrings. The towering, powdered hairstyles of the later 18th century were adorned with tiaras, aigrettes (feather-shaped ornaments), combs and hairpins, created using gemstones and any other material that caught the light. Parures – sets of jewellery pieces designed to complement one another, with matching gemstones or a common theme – often included as many as 16 items and were essential for fashionable ladies.

Apart from the flamboyant young men nicknamed Macaronis, Georgian men wore less jewellery than women. The fashionable man might wear decorative buttons and cravat pins studded with diamonds, gemstones and pastes, as well as gold signet rings. And nearly every man wore a pair of shoe buckles.

SHOE BUCKLES: THE LADY MAUFE COLLECTION

Since 1972, Kenwood has been home to one of the world’s largest collections of historical shoe buckles. It was the gift of Gladys Evelyn Prudence, Lady Maufe (1882/3–1976) – a designer, interior decorator and former director of the famed furniture maker and retailer Heal’s. She began collecting buckles in the 1960s and within ten years had amassed an important and comprehensive collection.

Numbering around 1,300 individual objects, the Lady Maufe Collection comprises Georgian and Regency shoe buckles made in Britain between about 1730 and 1820, as well as smaller numbers of early Victorian buckles and a selection made in continental Europe. This unique and fascinating collection reveals the changing fashions of the Georgian era and the skilful craftsmanship behind these forgotten accessories.

The fashion for shoe buckles

Shoe buckles first appeared in the mid 17th century, replacing ribbons (known as ‘roses’), which were previously used to fasten shoes. On 22 January 1660, Samuel Pepys noted in his diary: ‘This day I began to put buckles on my shoes.’ For the next 150 years, men and women of almost all classes wore shoe buckles. At first small, plain and utilitarian, they became larger and more elaborate as the 18th century progressed. They were completely separate and removable from shoes, so although they were functional, they could also serve as jewellery. Like other 18th-century clothing they were an important indicator of wealth and position.

Shoe buckles also reflected the changing fashions of the period. Exquisitely wrought designs in silver and gold, decorated with glittering pastes or precious stones like jet, garnet or diamonds, reflected the status of the wearer as well as the occasion. Cheaper buckles were made from copper, steel, brass and other metal alloys, and were usually plainer, although techniques were developed to make relatively affordable buckles look expensive. A Macaroni or Georgian fashionista might own as many as 50 pairs of buckles to cater for every occasion.

The buckle-making industry

English silversmiths and jewellers excelled at the highly skilled craft of buckle-making. The main centres of production were in the Midlands, especially Wolverhampton and Birmingham, while Woodstock near Oxford and Salisbury in Wiltshire also had a number of smaller workshops producing high-quality and expensive buckles. Retailers bought many of these and offered them for sale at fashionable stores.

By the mid 18th century, in Birmingham alone the buckle-making industry directly employed around 4,000 people, turning out almost 2 million buckles annually. Prices ranged from 1 shilling (about £6 today) to 5 or even 10 guineas per pair (over £1,000 today) depending on the type of decoration or weight of silver, which could be as much as 10 ounces (300g).

By the 1790s, however, shoe buckles were falling out of fashion, particularly for women. The flat-heeled slippers that became popular then and remained in style into the 19th century could not bear the weight of a large buckle and were secured with satin ribbons instead. This change in fashion reflected the social and political changes taking place in Europe. One of the slogans of the French Revolution was ‘Down with the aristocratic shoe buckle!’ In 1789, members of the National Assembly in France ceremoniously removed their silver and jewelled shoe buckles and gave them over to the cause of the Revolution.

By 1791, a petition protesting the decline of the buckle-making industry had been signed by 20,000 people working in the trade; but the shoe buckle’s heyday was over.

More about Kenwood’s collections

-

VISIT KENWOOD

Discover this hidden gem on the edge of Hampstead Heath, with its breathtaking interiors, world-class art collection and glorious parkland.

-

Kenwood Collection Highlights

Explore the gems of the Iveagh Bequest and a selection of the other works that make up the internationally renowned collection at Kenwood.

-

THE IVEAGH BEQUEST

Kenwood’s internationally important collection of paintings was bequeathed by Lord Iveagh in 1927. Find out about the collection and the man behind it.

-

The Suffolk Collection

This fine collection of royal and family portraits spanning the 16th to the 19th centuries includes internationally important paintings by William Larkin.

-

Rembrandt’s self-portrait with two circles

Learn about the historical and artistic significance of one of the finest surviving Rembrandt self-portraits, now a highlight of the Kenwood collection.

-

Old London Bridge

Take an in-depth look at this masterpiece by 17th-century Dutch artist Claude de Jongh, one of the Iveagh Bequest’s most popular paintings.

-

THE GUITAR PLAYER

Discover the story of The Guitar Player, one of only 37 known paintings by Johannes Vermeer.

-

Emma Hamilton, Artist’s Muse

Discover how George Romney’s portraits of Emma Hamilton, including The Spinstress, propelled its subject to fame.