Early history

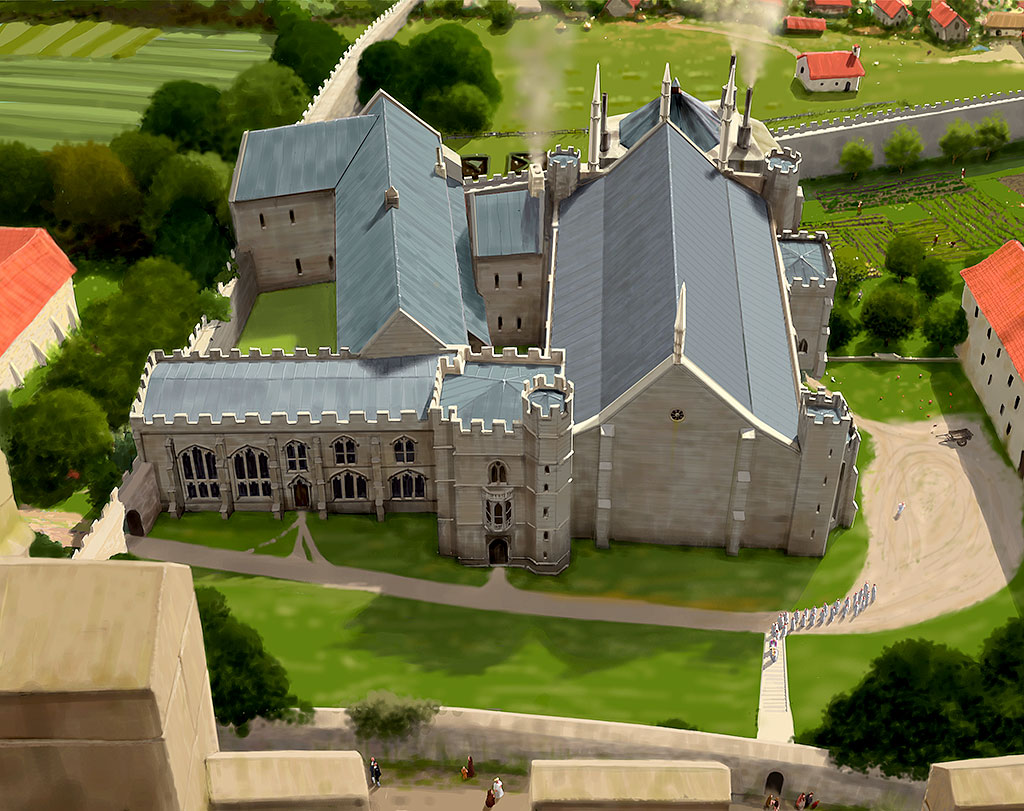

Lincoln became the seat, or base, for a bishop in 1072, when Bishop Remigius of Fécamp moved his seat from Dorchester-on-Thames to the hilltop there. Just six years after William the Conqueror’s great victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, this was a time of great upheaval in the governance of England. This included reforms in the administration of the Church and the construction of imposing cathedrals. Lincoln’s was among the largest and most impressive anywhere in Europe, and together with the nearby royal castle expressed the might of the new ruling Norman elite.

Initially the bishop of Lincoln seems to have lived either outside the city or within the castle. In about 1133, Bishop Alexander was given the Roman city gate to the north-east of his cathedral to use as a residence. But sometime between 1135 and 1138, King Stephen granted him the land which was to become the site of the medieval episcopal palace.

This was a time of significant political instability and civil war, and little work seems to have been done at the palace site initially. It was not until 1155–8, after King Henry II had regranted the site to Bishop Robert de Chesney, that building began in earnest. His work on the palace was apparently complete by 1163.

St Hugh

Lincoln was struck by disaster in 1185, when an earthquake destroyed the cathedral and possibly also the palace. The following year, Hugh of Avalon, an austere Carthusian monk known to history as St Hugh of Lincoln, was appointed bishop. A capable administrator and builder, he was also famed for the holiness of his life. He died in 1200 and in 1220 was canonised (declared a saint) by Pope Honorius III.

On his appointment Hugh immediately set about rebuilding both the cathedral and his palace. According to Gerard of Wales (1146–1223), who wrote a ‘Life’, or idealised biography, of St Hugh, the bishop started to build ‘splendid episcopal buildings, and intended, with God willing, to complete them in a grander and more magnificent style than the earlier ones’.

By the time of Hugh’s death, the east hall, which provided private accommodation and working space for the bishop and his household, had been completed. Work was also under way on the more public west hall.

The 13th and 14th centuries

The west hall and its associated kitchen and brewhouse were completed by Bishop Hugh of Wells (1209–35). In 1233 Henry III gave him permission ‘to dig and take stone in the ditch of the city near his house for the building of his house at Lincoln’. The following year, the king granted him 40 oaks from the royal forest of Sherwood for the roof of the hall. One of the largest covered spaces in 13th-century England, this was the public hall of the palace. Here the bishop entertained distinguished guests and conducted ceremonial business.

Work on the palace was continued by Bishop Robert Grosseteste (1235–53), who added an elaborate two-storey porch to the west hall. Located on its western side, it provided an imposing entrance to the hall. Its architecture was very similar to that of the ‘galilee’ porch which Bishop Grosseteste added to the south side of the cathedral. The two porches were probably linked by a ceremonial pathway, which the bishop and his entourage used for great religious ceremonies.

The next documented work at the palace took place in the early 14th century. In 1329, Bishop Henry Burghersh (1320–40) received permission from Edward III to crenellate (add fortifications to) the precinct walls that surrounded the palace. He also built a lodging house to the west of the site as a residence for his household of clerks and servants. This survives as Edward King House and is outside the area cared for by English Heritage.

Burghersh also acquired a terrace to the south of the palace to create a private garden, which would have been planted with formal flowerbeds.

Bishop William Alnwick

The palace then remained largely unchanged until the middle of the 15th century. This was a time when bishops and heads of monasteries across the land were investing in ecclesiastical architecture to indicate their piety, wealth and power.

William Alnwick, bishop of Lincoln between 1436 and 1449, was no exception. He built the imposing tower which now bears his name. Decorated with his coat of arms, it provided a grand entrance to the core of the palace complex and linked the private rooms in the east hall range with the public west hall. On the first floor of the tower was the bishop’s private bedchamber, with a fine oriel window looking out towards the cathedral.

Alnwick also built a chapel range adjoining his tower and renovated both the east and west halls.

Some notable bishops of Lincoln

Reformation

The last medieval works at the palace were undertaken by Bishop William Smith (or Smyth; 1495–1514). He built the outer gate that spanned the road leading from the cathedral close (where the cathedral’s clergy had their houses) to the palace.

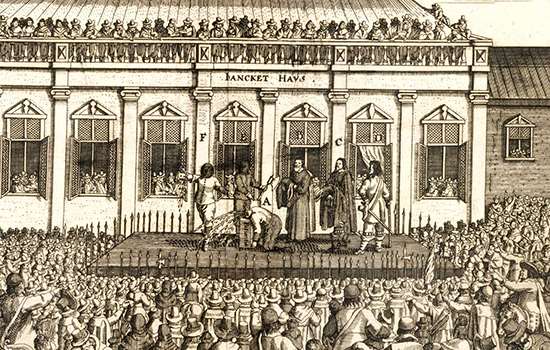

Within a generation, the bishops of Lincoln and their palace were caught up in the religious changes of the reign of Henry VIII. In 1536, the palace was attacked during the Lincolnshire Rising, a major rebellion occasioned by the king’s religious reforms and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Whatever damage was done, it must have been repaired by 1541 when Henry VIII and Queen Catherine Howard were entertained at the palace. One of the alleged ‘indiscretions’ that led to the queen’s downfall and her execution the following year was reported to have occurred at the palace.

King James I dined at the palace on 31 March 1617, and in the mid 1620s Bishop John Williams (1621–41) began a programme of repair and renovation.

Civil War

Bishop Williams’s work was never completed, however, because the repairs were overtaken by the onset of the Civil War between King Charles I and Parliament in 1642. In 1644, the city fell to Parliamentarian forces. The conflict left much of the palace in ruins: some of the buildings were destroyed by fire after a Royalist raiding party stormed the site, the lead roofs were removed (probably to make shot), and the fabric was robbed for building stone.

In 1652 Colonel James Berry, a Parliamentarian officer, converted some of the palace buildings into a modest house. Parliament had abolished the church hierarchy in 1646, so there was no longer any need for a bishop’s palace.

Bishop Robert Sanderson (1660–63) recovered the site on the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, when bishops were reinstated. But by then the buildings were considered beyond economic repair, the bishop favouring the bishops’ palace at Buckden (Cambridgeshire) as his residence.

Decay and rediscovery

The site suffered further damage in 1726 when stonework was removed from the ruins to repair the cathedral. The 14th-century west range, however, remained in occupation and was modernised to provide a fashionable Georgian residence. By now the core of the heavily ruined medieval palace was little more than a picturesque garden feature.

Rediscovery of the site started in the early 19th century. In 1836, Charles Mainwaring secured a lease of the site and initiated clearance of the ruins. Edward Willson, a noted antiquary and surveyor to the county of Lincolnshire, made a detailed survey of the medieval remains.

The 19th and 20th centuries

The bishops of Lincoln returned to the site of the palace in the mid 19th century. In 1878, Bishop Alnwick’s Tower was restored to provide lecture rooms for the recently established Lincoln Theological College. Bishop Edward King (1885–1910) renovated the chamber block at the south end of the west hall as a chapel for the bishop. Dedicated to St Hugh, it remains a chapel and is outside the area cared for by English Heritage.

However, the medieval halls were too damaged to be restored, and the Victorian palace was established in the 14th-century west range and an adjoining building. The ‘Gothic’ architecture harkened back to the medieval past and was in keeping with Bishop King’s ‘High Church’ beliefs.

By 1945, the palace was seen as too large and costly for the diocese. The bishops moved out, and the buildings were converted into office and conference space and more recently a hotel. In 1954, the ruins of the medieval palace were placed in the guardianship of the Ministry of Works, a predecessor of English Heritage.

Renovations and repairs

Between 2021 and 2023, English Heritage carried out a major programme of repairs and conservation, to halt the decline of the stonework and safeguard the buildings for the future.

First, a laser scan of the buildings helped identify an appropriate method of repair for each area, using computer modelling software. A team of specialist stonemasons then removed damaging vegetation from the ruins.

Repairing and replacing masonry has been key to safeguarding the ruins. The historic stonework has been retained wherever possible, and in exceptional instances has been replaced with new stone. The Lincolnshire limestone used in the palace is now in short supply, but replacement stone – from Lincoln Cathedral’s quarry – has been used where the existing masonry was beyond repair. Traditional lime-based mortars have been used, which are much more compatible with the stonework than cement-based mortar. To protect the wall tops – a prime area where water and vegetation can cause damage – a variety of cappings have been introduced across the site, ranging from hard stone slabs to soft turf.

The high-quality work and excellent craftsmanship mean that the palace is now more resilient to the challenges it faces, including climate change.

Read more about the conservation projectFind out more

-

Visit the palace

See how we’ve safeguarded the home of Lincoln’s medieval bishops.

-

WHAT BECAME OF THE MONKS AND NUNS AT THE DISSOLUTION?

Discover what happened to the many thousands of monks and nuns whose lives were changed forever when, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England was closed.

-

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.