Lydford Law and Parliamentary Privilege

From a Tudor ‘tinner’ to a 21st-century footballer: how the Privilege of Parliament Act can be traced back to the ghastliness of prison life at Lydford Castle in Devon.

LYDFORD PRISON

Lydford Castle really ought to be known as Lydford Prison. Indeed, the historian Andrew Saunders described it as ‘the earliest example of a purpose-built gaol’ in England. It was constructed at the end of the 12th century, and its central purpose quickly became the administration of local laws – and the imprisonment of those who dared to flout them.

The castle was even redesigned in the middle of the 13th century to resemble an archaic symbol of punitive authority, the ‘motte and bailey’. This involved burying the ground floor of the tower under a mound of earth, which had the additional advantage of forming an underground pit to house the lowest status prisoners.

GUILTY UNTIL PROVEN INNOCENT

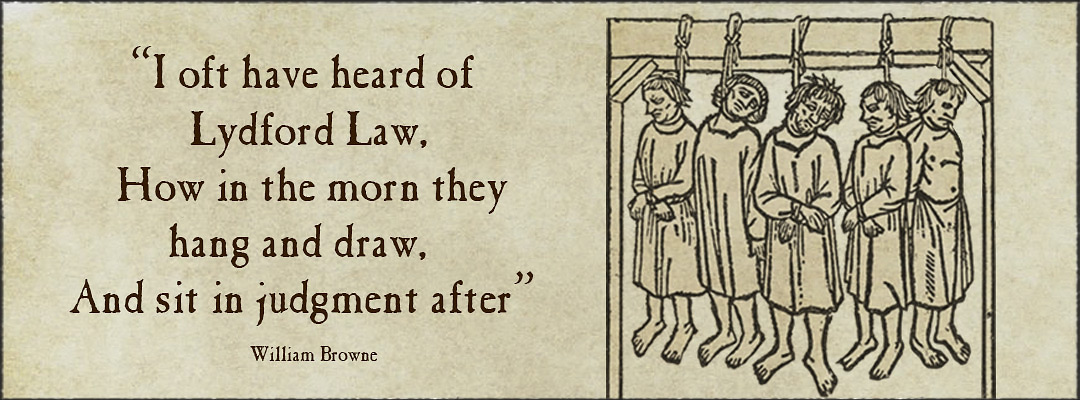

I oft have heard of Lydford Law,

How in the morn they hang and draw,

And sit in judgment after:

At first I wondered at it much;

But since, I find the reason such,

As it deserves no laughter.

So wrote William Browne in a 1644 poem, reflecting Lydford Castle’s remarkably enduring reputation for backward justice. Indeed the phrase ‘Lydford Law’ was used as an idiomatic shorthand for judicial cruelty for centuries.

The roots of this reputation are unclear, although one likely factor was the tendency of the court that sat at the castle to hang offenders on the assumption that the parallel court – which was actually entitled to make such judgments – would pass the same sentence. The latter court only sat once every three years!

TIN-POT DICTATOR

Probably the best-known victim of ‘Lydford Law’ is the MP Richard Strode, who in 1510 attempted to introduce legislation limiting the rights of tin miners on Dartmoor. They were, Strode asserted, damaging Devon’s ports and estuaries with mining debris.

Because Strode was himself a ‘tinner’, an influential competitor was able to bring charges against him at the Stannary Court which sat at Lydford Castle, and Strode was fined £160. When he refused to hand over the sum, he was imprisoned at Lydford for three weeks.

Despite his relatively short sentence, he later described the gaol as ‘one of the most annoious, contagious and detestable places wythin this realme’. His account also included mention of being thrown into ‘a depe pit under the grounde’, fed only bread and water, and locked in leg cuffs until he was able to bribe one of his keepers to remove them.

PRIVILEGED POSITION

Strode was eventually released thanks to a letter from the Exchequer, and returned to Parliament.

He wasted no time in petitioning his fellow MPs to pass an act granting them all immunity from prosecution based on parliamentary activities – a piece of legislation designed both to reverse the local court ruling that resulted in his imprisonment, and to protect him and his colleagues from similar cases in the future.

The Privilege of Parliament Act passed into law in 1512 and remains commonly known as ‘Strode’s Act’ to this day. And the resulting constitutional phenomenon, Parliamentary Privilege, also endures.

It was put to the test as recently as 2011, when the MP John Hemming named Ryan Giggs, a famous footballer who had taken out a court injunction to stop details of an extramarital affair going public, during a parliamentary debate. Thanks to Strode’s Act, Hemming wasn’t prosecuted.

By Sam Kinchin-Smith