Q: When was the garden at Marble Hill created?

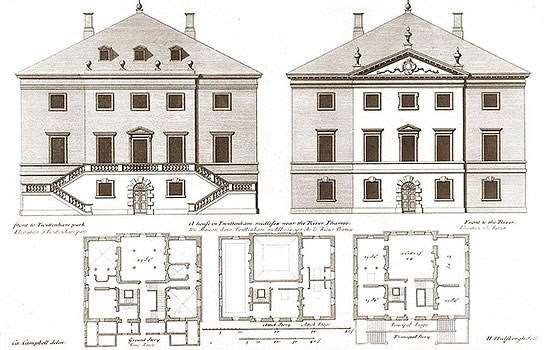

A: We know that Henrietta Howard (1689–1767) considered the design of both her new house and her garden, which ran from the house down to the river Thames, at the same time. In 1724 Roger Morris, whom she commissioned to build the house, received payments which include references to creating features in the garden. Through the rest of the 1720s we know that Henrietta continued to lay out different parts of the garden. A complaint from a neighbour in 1725 indicates that lots of trees were being planted at that time.

Henrietta probably continued to make small changes and additions to the garden throughout her lifetime.

Find out more about Henrietta HowardQ: How do we know what the garden looked like in Henrietta’s lifetime?

A: For many years, the only clue we had as to the layout of the garden was an engraving made in about 1749. This shows the terraces that slope towards the river, and groves of trees.

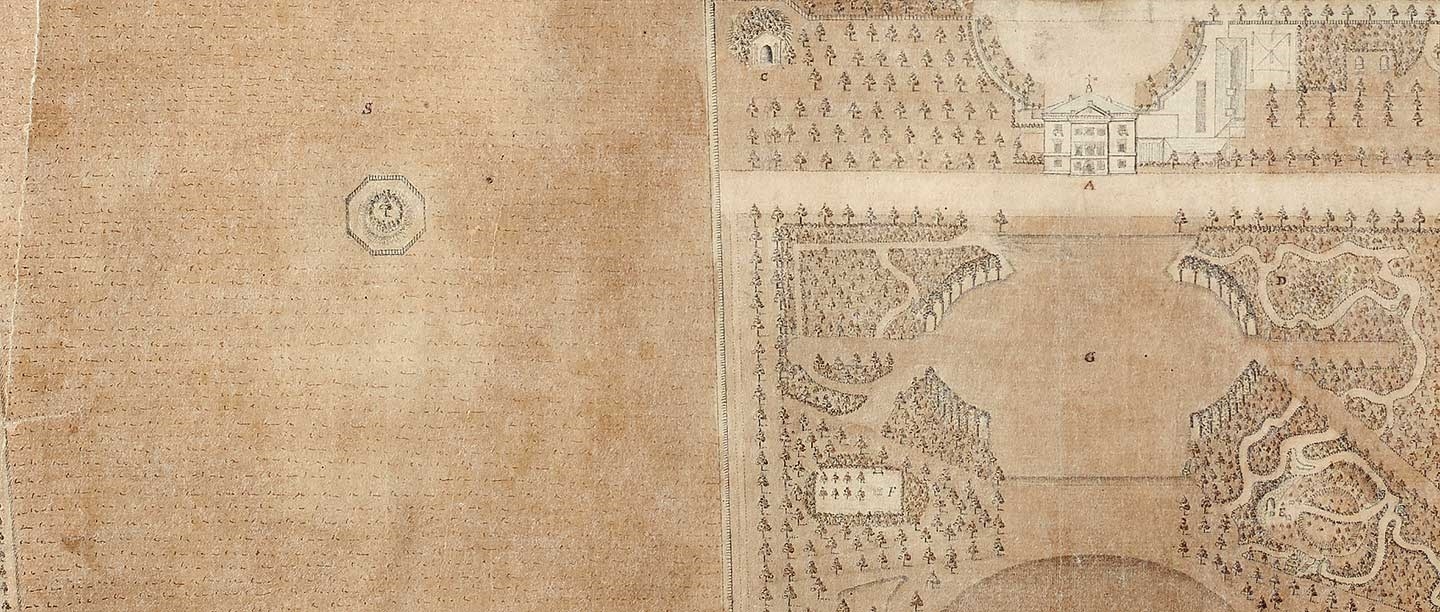

However, in 1991 a plan was placed in the Norfolk Record Office which showed the garden in about 1749. This had never been studied in detail in its own right until 2014, when English Heritage was compiling a new conservation management plan for the site. Previous research indicated that the plan may have dated from about 1752 and may have been created to help support Henrietta’s case in a legal dispute over an area of land.[1]

However, local researchers noticed that on the reverse side of the plan the outline of the coastline of Scotland was drawn. A comparison of this with maps of Scotland drawn in the 18th century showed that it matches one drawn by James Dorret and published in 1750. Dorret was a land surveyor for the Duke of Argyll (one of Howard’s trustees). Argyll bought land on Howard’s behalf as her trustee in 1724 and transferred it to her in 1748. It is possible that the plan is a record of the estate when Argyll transferred it to Howard in the late 1740s. This could explain why the plan shows the whole estate (rather than just the area involved in the legal dispute) and why the land is measured in the plan’s schedule. It is not inconceivable that it was a gift, explaining the care taken in delineating the garden and cartouche, though there is no direct evidence to support this.

Q: What does the plan show?

A: When I saw the plan for the first time, I was fascinated by both its scale (it’s probably about a metre square) and by how detailed it is. It shows everything that was in the garden at the time, right down to the exact location and design of individual seats.

The plan includes a key, which labels many of the garden features including a Green House, Ice House and Ice House Seat, Flower Garden, Ninepin Alley and Grotto. It also shows the layout of the garden, allowing us to recognise – for the first time – that it was based on ideas from classical literature and the gardens of ancient Rome. And it shows us lots of detail of planting – where hedges were located, as well as distinguishing between groves (trees laid out in a regular formation), orchard, wilderness areas and densely planted areas or thickets.

Q: How do you know the plan is accurate?

A: The detail on the plan, including a scale, exact measurements, explanations of land holdings and the inclusion of elements such as the poultry yard and cow house (which would not usually be individually listed), indicates that it is a plan of what was there, rather than a design proposal. As a detailed plan of the estate it shows how the garden was laid out at the time it was drawn. The style of the garden shown on the plan reflects fashionable garden design in the 1720s – by the late 1740s and early 1750s this style of garden was no longer being advocated.

In spring 2016 Historic England made a comprehensive landscape survey using non-invasive techniques such as aerial photography, LiDAR, geophysics, analytical earthwork survey and tree stump identification. When the results were collated they provided significant evidence that the plan was accurate. They also showed us areas where archaeological excavation might provide a better understanding of the survival of features shown on the plan and how they were built.

Download the landscape surveyDuring excavations in March and August 2017, archaeologists discovered evidence for the Ninepin Alley in the exact spot where it is shown on the plan. On the plan, the playing area shown is about 3 metres by 15 metres, and on the survey you can even see the individual nine pins laid out in a square. Although no trace of the alley remained above ground, the excavators found what we think is the surface of the playing area. It had been repaired several times, showing it was well used.

The archaeologists also investigated the area around the grotto. They found that this was much more complex than had previously been understood, and closer in scale to the design shown in this area on the plan than the current layout suggests.

Q: Do we know who designed the garden at Marble Hill?

A: When creating her home at Marble Hill, Henrietta was surrounded by a large circle of influential and opinionated figures, especially when it came to garden design. This group included Lord Bathurst (Riskins Park and Cirencester Park), Lord Peterborough (Parson’s Green and Bevis Mount), and Lord Ilay, later 3rd Duke of Argyll (Whitton Park). Lord Ilay, who was one of Henrietta’s trustees, was involved in purchasing the land at Marble Hill on her behalf. Interestingly he also employed the same gardener as Howard, Daniel Crafts. All her friends probably had varying degrees of involvement in advising Henrietta on the design of the garden.

Alexander Pope, however, seems to have been one of the most influential, with many references to his involvement in the design in accounts, correspondence and poems. In 1724 Henrietta Howard, Pope and Charles Bridgeman, later gardener to George II, met on site to discuss the design and layout of the garden. Pope, a close friend of Henrietta, was laying out his own garden in Twickenham at the time. A plan for the Marble Hill garden (also in the Norfolk Record Office) is almost certainly his. Although some elements of his design were carried through to the final layout, including an oval lawn on the terrace nearest the house, the final design was different, and was probably a combination of Pope’s and Bridgeman’s ideas. Bridgeman is also recorded as providing a plan for the garden, but this either has not survived or has yet to be discovered.

Q: Why is the garden so important?

A: Both Pope and Bridgeman were at the forefront of changing fashions in garden design. Pope’s writings advocated a style that complemented the newly popular Palladian style of architecture, which was inspired by classical literature and the villas of the ‘ancients’. This was the beginning of a move away from the formal gardens of the late 17th century. From the 1730s another new style took hold, which encouraged the creation of an idealised pastoral landscape dotted with classical temples and statuary – a style known today as the English landscape garden.

Marble Hill is important because it is a rare surviving example of a style of garden created during a period of stylistic transition, when completely new ideas about garden design were being formed.

Q: What inspired an ‘ancient’ garden?

A: Pope is often regarded as one of the first to promote following ‘ancient’ principles in the garden. Much of his inspiration came from the classical texts he was translating, such as the Odyssey, and this, along with his painting principles, was the basis for the layout at Marble Hill. He was probably also familiar with the letters of Pliny the Younger (c.AD 61–112) about his villas at Laurentum and Tuscum. These letters were published in 1728 in Robert Castell’s Villas of the Ancients Illustrated, accompanied by plans drawn by Castell from Pliny’s descriptions.

Many ‘ancient’ principles can be seen at Marble Hill, including the winding wilderness areas and the layout of the groves of trees, terraces and grottoes, showcasing Henrietta’s enthusiasm for this ‘ancient’ style of design.

Q: How did Henrietta use the garden?

A: In 1742 George Grenville describes how Henrietta used the Green House as a place to relax – we even know that it included sofas where she could lay her ‘lazy limbs’. But it wasn’t all relaxation. We know that from the 1730s Henrietta and her great-niece decorated the grotto with shells – in 1762 her great-niece complained of hurting her hands in the process. Grotto decorating was seen as a ‘polite’ occupation for women at the time.

The Ninepin Alley epitomises the idea of the garden as a place where Henrietta and her friends could enjoy playing a game together. The large oval lawn of the upper terrace, near the house, was probably used for entertaining and dining.

Q: What about the rest of Marble Hill Park? Did Henrietta’s garden include that?

A: The garden itself occupied only the area between the house and the river. However, Henrietta’s wider estate covered almost exactly the same area as the park today. The areas now used for rugby, cricket and football were meadows used for keeping animals, including cows and sheep. In the area now covered by the car park, adventure play area and ranger's office were Henrietta’s coach house, stable yard and kitchen garden. These are all shown in detail on the c.1749 plan.

The kitchen garden supplied food for Henrietta not only when she was at Marble Hill but also when she was at her town house in Savile Row. In the 1750s we know she was sending celery, endive, spinach, potatoes, turnips, carrots, horseradish, onions, parsley, grapes, walnuts and parsley to her town house, to list just a few!

Q: What happened to the estate after Henrietta?

A: After Henrietta’s death in 1767, the house survived more or less unaltered until 1898, when it was sold to the Cunard family. They planned to turn the park into a housing development, but met with strong local opposition, largely because this would have spoilt the rural view from Richmond Hill. London County Council purchased the site in 1902, and the following year Marble Hill opened as a public park.

Read more about saving the view from Richmond HillQ: Is English Heritage working to restore Henrietta’s garden?

A: As part of the Marble Hill Revived project, English Heritage has restored the key elements of Marble Hill’s garden. Gardeners and volunteers, working alongside contractors, have reinstated the all-but-lost design, opening up previously inaccessible woodland areas and installing serpentine paths. The avenues of trees from the house to the river have been replanted, recreating the view that Henrietta and her guests would have enjoyed. Henrietta’s ninepin alley has also been recreated following archaeological investigation and the grotto has been restored to its 18th-century appearance.

Across the wider park, the planting of trees, flowers and shrubs has improved biodiversity and newly established wildflower meadows are encouraging wildlife such as grasshoppers and butterflies.

Footnote

1. D. Jacques, Gardens of Court and Country: English Design 1630–1730 (London, 2017).

FIND OUT MORE

-

Henrietta Howard

Though mainly known as the mistress of George II, Henrietta Howard was a remarkable woman in her own right. Read more about her extraordinary life and how she came to build Marble Hill.

-

History of Marble Hill

Read a full history of this English Palladian villa and its gardens beside the Thames, from its origins in the 1720s as a retreat from court life for Henrietta Howard to the present day.

-

The Gardeners that time (almost) forgot

Discover the stories of some gardeners of the past, including one of Henrietta Howard’s gardeners at Marble Hill.