The Peels

Jonathan Peel (1799–1879) was a Conservative MP from 1826 and the son of one of the wealthiest textile manufacturers of the early Industrial Revolution. His eldest brother, Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, served as Prime Minister in 1834–5 and 1841–6. In 1824, Jonathan married Alice Kennedy (1805–87), the youngest daughter of a Scottish peer, and they moved into Marble Hill the following year.

Marble Hill was a family home to Jonathan and Alice’s eight children. The Peels’ letters give a wealth of insights into family life at the house. Contrary to our inherited vision of a detached Victorian father, Jonathan was very involved in the lives of his children. This is particularly evident in his letters to Alice during times when she was away, when he reported in detail on the social engagements of their daughters.

While their five sons left to attend school around the ages of 10 or 11, two of the Peels’ daughters lived at the house until marrying in their late twenties, and Margaret, or ‘Mag’, their eldest daughter, never married and lived at Marble Hill almost all her life. The letters reveal many small details of Margaret’s daily activities at the house: visiting her nearby relatives, journeying into London with friends, and on one occasion visiting an exotic bird show with her father at the Crystal Palace. Margaret also seems to have performed administrative tasks for her parents as they grew older, helping to organise the household accounts.

Jonathan’s Race Horses

Jonathan was a keen race-horse owner and breeder. Soon after purchasing the house, he made the Peels’ main architectural addition to Marble Hill: the stable block.

The stables housed horses for the family’s carriages, including a Brougham carriage which took family members around London, and at times Jonathan’s race horses. When Jonathan advertised race horses for sale, potential buyers could view them on-site.

A lifelong racing enthusiast, Jonathan owned numerous successful race horses. When he sold several breeding horses in 1851, they went for 12,000 guineas in total – the equivalent of 63,000 days’ wages for the average skilled tradesman. In 1879, the year of his death, Jonathan’s horses had been due to compete in more than 50 races. When the house and its contents were sold in 1887, the catalogue referenced four oil paintings depicting ‘a favourite horse’.

Luxury in Reach of London

The Peels’ choice of Marble Hill as their main residence was probably due to its situation within the picturesque suburb of Twickenham. By the 19th century, the Richmond and Twickenham area had been a politically and socially significant landscape for hundreds of years. The area also had family connections for them. When the couple bought Marble Hill in 1825, Alice’s parents – Margaret and Archibald Kennedy, 1st Marquess of Ailsa – had been living nearby for several years. They had built St Margaret’s House down-river, a now demolished villa that still lends its name to the neighbourhood north of Twickenham.

As the suburbs and railways grew exponentially, it became possible to commute to the city for work. The Peels had a London address at Park Place by St James’s Palace, but Jonathan’s letters reveal he did not think it necessary to be so central. Instead, he often walked to the station at Richmond before taking the train to Waterloo and heading for the Houses of Parliament.

In one fascinating letter from 1862, Jonathan describes party in-fighting over a Bill that would allow Queen Victoria to lessen her workload, by signing fewer commissions. This was a thorny issue, and she entrusted Jonathan with fully explaining her motives to Parliament, hopeful that he could win over the House of Commons. Parliament regularly sat late into the night. Although Jonathan knew it would mean undermining the Queen’s wishes, reluctant to miss the last train at 11.45pm, he left the House for Marble Hill, missing the conclusion of the debate.

Guests at Marble Hill

Marble Hill’s proximity to London made it a desirable location for hosting and entertaining. The Peels regularly received prominent political and royal figures, from the Duke of Wellington to Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, the latter often visiting at late notice to drink tea or play a game of croquet.

Very few letters written by Alice herself survive, but the wealth of correspondence she received shows a wide and influential social circle both at home and abroad. In an 1855 diary entry, Liberal politician John Bright describes attending one of Alice’s luncheons alongside ministers of Saxony and Prussia, as well as Viscountess Beaconsfield and her husband, future Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli.

Alice also had very strong connections to French politics. She was close friends with French prime minister François Guizot and his influential partner Princess von Lieven.

After the French Revolution of 1848, the area to the west of London became an important refuge for the ousted French royal family. Henri d’Orléans – son of the French king Louis-Philippe I and leader of the monarchist faction – settled at Orleans House, adjacent to Marble Hill. His brother Antoine, Duke of Montpensier, rented Marble Hill from the Peels in 1865.

Upon Alice’s death in 1887, the Marble Hill sales catalogue indexing the family’s possessions reflected their social circle. Alongside portraits of the Dukes of Wellington and Devonshire were three pictures of Henri d’Orléans and his wife, and one of the Duke of Nemours – another son of King Louis-Philippe I.

The Live-in Staff

Alongside the family, there were often around 12 servants living at Marble Hill working in the house, stables and gardens. In a letter to Alice, Isabella Cecil, Marchioness of Exeter, recalled Alice telling her that she much preferred the ‘society of foreigners’. Alice’s preferences for the continent were reflected in her household’s staff: she employed French, Swiss and German ladies’ maids, as well as French and Austrian cooks.

Throughout the 1860s, Jonathan also employed a French valet, Nicholas Beck, whose role was to assist with anything from domestic tasks to paying bills and handling money. Beck appears frequently in the Peels’ letters, helping Jonathan prepare for political functions and dinner parties, collecting Jonathan from the station in the Brougham carriage, or waiting up at home to greet him after a late session in Parliament. Beck was reportedly able to calm and brush the family’s dog, Pie, even when he was inclined to resist.

Like many large houses, Marble Hill also had a dairy. The census returns only ever reveal a single dairy maid living on-site, but others may have lived locally. The pure-bred Jersey cattle that the Peels kept were renowned for their high-quality milk. In one short letter to Alice, Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge requests a delivery of some of Marble Hill’s beautiful cream cheese.

Pie, the Dog

Living with the Peels at Marble Hill from at least 1858 was their dog, somewhat comically named ‘The Pie’ or simply ‘Pie’. While we do not know the origin of his name, from his frequent mention in Jonathan’s letters to Alice it is clear he was as much a member of the family as any of the Peels themselves. On one occasion, ahead of his return from visiting Queen Victoria at Balmoral, Jonathan asked Alice to invite Pie to join him for ‘a very late dinner – he will understand you perfectly’.

The family’s affection for the dog is clear, despite his apparently fiery personality. In another letter to Alice during one of her stays in Paris, Jonathan reports the delivery of an anonymous gift to his desk at the War Office. Dedicated to ‘the secretary of state and his quarrelsome dog’, it was a book containing a series of prints depicting a hound identical to Pie. The book is lost and no known photos of Pie survive, but his many escapades live on in Jonathan’s letters.

Image: An illustration of dogs dating from the mid 19th century, by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A Servant Scandal

Trusted servants regularly shopped on behalf of their mistress or master, a system that could easily be exploited, particularly in larger towns and cities. This might involve appropriating real servants’ identities or running up shop debts using the names and addresses of fictional employers. In 1828, Marble Hill was entangled in such a case.

Two months after leaving her role in service at Marble Hill, 22-year-old Mary Ann Bell visited Howell, James & Co., a famous jewellers and silversmiths on Oxford Street in London. She purchased £70 of goods under the name of Lady Alice Peel, incurring a considerable debt for her previous employer. Account books giving servants’ wages do not survive for Marble Hill, but this would have been well over a year’s earnings for a maid like Mary Ann.

While Mary Ann was held in Newgate Prison, Jonathan petitioned to have her moved to the penitentiary, believing it less of a moral threat to her previously respectable character. The petition was granted, but Mary Ann Bell was ultimately sentenced to seven years’ transportation to a penal colony. Prosecutions for fraud took the intent of the accused into consideration, resulting in severe punishments for deception as much as for loss or theft of goods.

Marble Hill remained the main residence for the Peels for the rest of their lives. Jonathan died in 1879 and the widowed Alice continued to live at the house with her eldest daughter, Margaret, for another eight years. By the time of her death in 1887, Alice had become Marble Hill’s longest-term (and last) resident, having lived there for over 60 years. After her death, Marble Hill went up for sale and Margaret received a settlement from her parents’ estate to fund her life elsewhere. She died just three years later and is memorialised at Holy Trinity Church in Northwood, near Ruislip.

Written by Leonie Price, PhD student at the University of Sheffield

Header image: Photograph of a selection of letters to Alice Peel from the Papers of the Morier Family, Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts

© Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Balliol College

More stories from Marble Hill

-

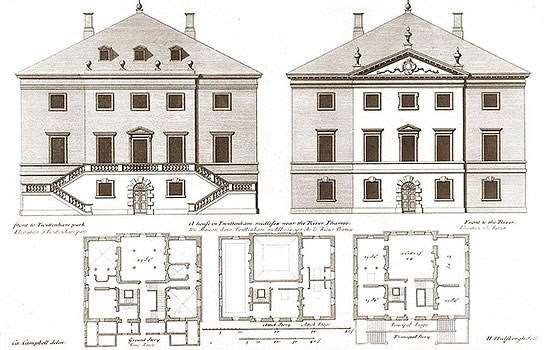

History of Marble Hill

Read a full history of this English Palladian villa and its gardens beside the Thames, from its origins in the 1720s as a retreat from court life for Henrietta Howard to the present day.

-

Collection Highlights

Explore some of the key items from the collection at Marble Hill, which reveal Henrietta Howard’s taste and status.

-

Henrietta Howard

Though mainly known as the mistress of George II, Henrietta Howard was a remarkable woman in her own right. Read more about her extraordinary life and how she came to build Marble Hill.

-

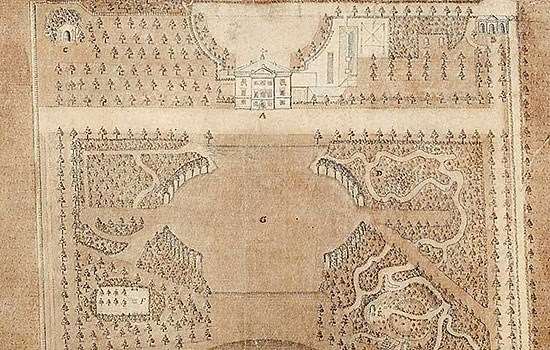

Henrietta Howard’s Garden at Marble Hill

Find out what makes the garden between the house and the river at Marble Hill so significant, and how English Heritage has restored its key elements.