Roman villas

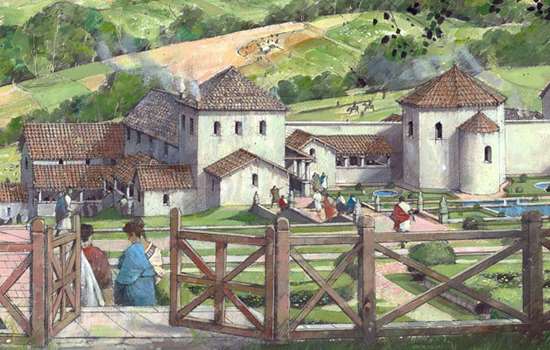

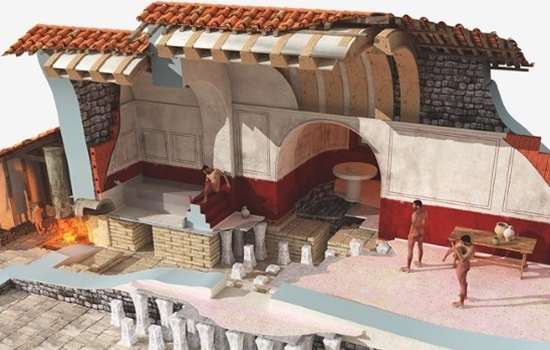

Villas were houses in the countryside, usually associated with agricultural holdings or estates. They ranged from modest structures to huge complexes, but usually incorporated one or more features that were distinctly Roman in origin, notably underfloor heating, bath-houses, concrete floors, mosaic pavements, and plastered and painted walls. Rooms were clearly separated for different purposes – cooking, dining, bathing, working and sleeping. The agricultural functions of villas were often fulfilled in separate but clearly associated buildings.

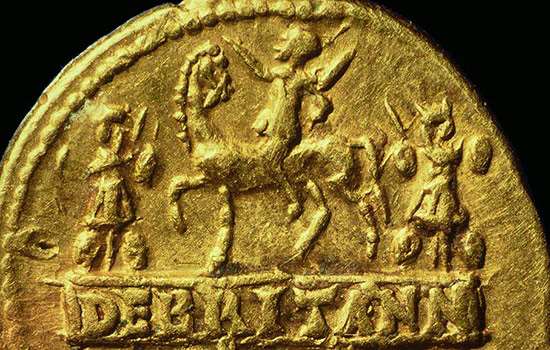

Villas in Britain were built with Roman techniques and embody Roman culture. However, many would have been the homes of an indigenous elite. During the conquest period the Romans induced many of these people to form an administrative class for the new regional towns and the surrounding countryside of the former tribal areas. This elite probably lived comfortably, perhaps enjoying both fine town houses and rural estates with villas.

A few villas may have been the homes of senior imperial officers and career administrators who had been appointed to provincial posts by the Roman state. Such officials were drawn from all over the empire and moved on every few years. A marble bust found at one villa, Lullingstone in Kent, has been identified as Publius Helvius Pertinax, governor of Britannia in AD 185–6 and briefly emperor, in AD 193. The villa may have been his country residence.

North Leigh in Roman Britain

The villa at North Leigh is in the valley of the river Evenlode, about 850 metres south of Akeman Street, a major east–west Roman road linking the important provincial towns of Verulamium (St Albans, Hertfordshire) in the east and Corinium (Cirencester, Gloucestershire) in the west. The villa probably fell within the administrative orbit of Corinium, the tribal capital of the Dobunni people.

Akeman Street also ran between two other Roman arterial roads – the Fosse Way, which linked Isca (Exeter, Devon) with Lindum (Lincoln), and Watling Street, running all the way from the south-east coast at Rutupiae (Richborough, Kent) to Viriconium (Wroxeter, Shropshire).

This location placed the villa at the heart of Roman Britain. It sits on the edge of the river’s alluvial floodplain, close to the valley bottom and near a pronounced loop in the river, which may have moved further from the villa since Roman times. With such good communications and fertile soil, the villa was well sited to exploit the region’s rich agricultural resources.

Finds from beneath the villa include pre-Roman pottery, hearths and metalworking slag. These indicate that an existing farm was probably adapted in the early part of Roman rule, and was the precursor of the first villa buildings.

The first villa

The villa developed over 300 years. Archaeologists have identified five broad phases of construction, although the exact dating and details of each phase are unclear.

The first villa was probably erected in the early 2nd century AD and comprised three separate buildings arranged close together roughly north–south in a line – a dwelling, a hall and a bath-house. All went through changes and additions, with the dwelling and hall merged into one structure. The bath-house was only integrated at the end of this phase.

Probably by the mid 2nd century, the villa also had short wings extending eastwards from both ends.

Download a plan of the villaThe first rebuilding

This villa, including the baths, was partially demolished, probably in the 3rd century. It was replaced with new buildings, particularly a new main range built on the same alignment and using some of the old foundations. This comprised a set of rooms fronted to the east by a continuous veranda, which served as a corridor. The two wings were extended, also with corridors.

Some rooms in the new main range had an underfloor heating system, or hypocaust, in which hot air from a furnace was drawn along channels under the floor and up flues in the walls, thereby warming the rooms. The underfloor channels and the openings in the wall that brought hot air from the furnace are still visible.

Read more about Roman bathing

The courtyard villa

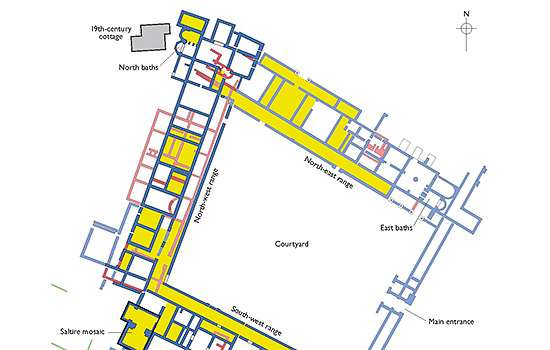

The villa was greatly expanded, beginning in the late 3rd or early 4th century, to create a huge building around a courtyard. The pre-existing villa formed its north-west range and the short wings were extended to form long north-east and south-west ranges, which were joined by a further range on the south-east side. This closed off an area to create a large central courtyard, which may have included a garden.

The south-east range was a colonnaded corridor with rooms only at the centre of the range, perhaps forming a lodge at the entrance to the courtyard. The corridor in this range connected to another that ran around the entire courtyard and gave access to the villa rooms.

The size and luxurious nature of this courtyard villa show that it must have belonged to wealthy and powerful people. It had a new suite of baths (the north baths, on the site of the demolished baths of the first villa) at the junction of the north-east and north-west ranges, and another bath suite at the other end of the north-east range (the east baths). All the other rooms in the north-west and north-east ranges were residential. The discovery of four ovens in one room of the south-west range indicates kitchen and service functions there, and a further bath suite nearby (the south baths) may have been intended for servants and slaves working on the estate and in the villa.

Many rooms and corridors had floors with mosaic pavements and painted plaster on the walls. One fine mosaic floor survives in situ in a former dining and reception suite at the junction of the north-west and south-west ranges.

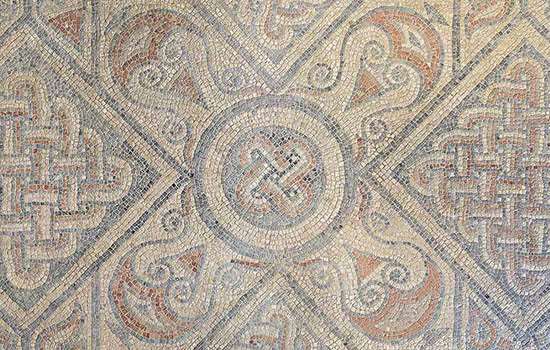

The mosaics

The villa has produced evidence for at least 19 mosaic floors, though only one remains visible today. Some were elaborate and others plainer, and most had geometric designs. The oldest was laid in a room of the north-west range sometime in the 2nd century AD. Its style is like that of mosaics associated with craftsmen operating from the Colchester and St Albans areas.

The other mosaics are mostly associated with the courtyard villa. They were installed at different times in the first half of the 4th century, in all three main ranges. Often they were laid on raised floors heated by hypocaust systems. Where sufficient tesserae (the small cubes, usually of stone, tile or brick, used to make the mosaic) remained in place, experts have been able to identify the mosaics from their motifs and designs as work of a ‘Corinian school’. We know from the study of hundreds of mosaics that mosaic craftsmen in different parts of Britain came to be organised into local ‘schools’, which developed distinctive regional styles and designs. Over time, a style developed by one or more workshops in Corinium was adopted and developed by other workshops in the area.

The surviving mosaic at North Leigh formed the floor of what was probably a reception and dining suite, in two rooms partially divided by an arch but with a single round-vaulted ceiling. Thought to have been laid in the rooms in about AD 340, it employs a distinctive motif – a saltire, or diagonal cross – which may have been adopted by several workshops of the Corinian school, sometimes referred to as the Saltire Group.

The North Leigh floor uses tesserae coloured blue-grey, red, yellow ochre and cream, with the saltire as a repeating dominant element of the pattern. A knot-like running design known as guilloche is used for the borders and areas dividing the saltires.

Read more about the mosaicLater changes and other buildings

Various modifications were made during the life of the courtyard villa. Notably, in the north bath-house, some rooms went out of use and others were added in the mid 4th century. In one of the disused rooms, a hoard of counterfeit coins and materials used for making them had been dumped or concealed, possibly in a bag – fabric fibres were found attached to one of the coins. The coins are of the mid 4th century, making it possible to date the hoard and the changes in the bath-house.

Aerial photographs and geophysical survey have revealed the outline of further, extensive buildings south of the courtyard villa and aligned with it. These have not been excavated but may be further domestic structures or, more likely, the farm and service buildings of a considerable agricultural estate. They include a probable boundary wall and ditch to the south and west of the villa, on an alignment that might suggest the whole villa complex stood within a walled enclosure.

Decline

People were still using the villa in the late 4th and early 5th centuries, at the end of the Roman administration of Britain, but they seem to have been of lower status than those who had lived there earlier. The building of rough walls across mosaic floors, and hearths made on them, suggest that the use of the villa was utilitarian. Very coarse, shelly pottery was in use, and in one room a large amount of animal bone, probably from a midden (a rubbish dump), was deposited.

There is also evidence that some structural materials, including ceramic tiles and stone roofing slates, had been deliberately dismantled and stored, possibly for reuse elsewhere.

Despite these traces of people occupying the villa after Rome abandoned Britain, there is no evidence that this occupation lasted long, and the once magnificent building fell slowly into decay.

Discovery of the villa

The villa was first recorded in 1783 by Thomas Warton as ‘a spreading tumulus, consisting of rubbish and fragments of Roman bricks and cement’. It was extensively excavated between 1813 and 1817 by Henry Hakewill.

Hakewill located and exposed several fine geometric mosaics, a discovery which produced much excitement in the area and attracted many visitors. However, although the landowner (the Duke of Marlborough) built sheds to protect two of the mosaics, only one mosaic survives today: the others were destroyed by the ravages of frost, and over-enthusiastic visitors who removed tesserae as souvenirs. Fortunately, Hakewill produced drawings of five of them, including the surviving mosaic.

In 1910–11 Donald Atkinson and Evelyn White re-excavated the site, which made it possible to establish the complete plan of a courtyard villa. Further excavations have taken place since, on a smaller scale, including in 1956–9 and 1975–7, when the counterfeiter’s hoard was found.

Today, parts of two ranges of the courtyard villa are consolidated and displayed for the public, and the mosaic can be viewed on set days each year. The remaining two ranges are now buried to prevent damage and erosion.

By Paul Pattison

Find out more

-

VISIT NORTH LEIGH ROMAN VILLA

The remains of a large, well built Roman courtyard villa. The most important feature is a nearly complete mosaic tile floor, patterned in reds and browns.

-

AUDIO GUIDE TO THE VILLA

Stream or download this audio guide to explore the remains of North Leigh Roman Villa and learn about its history.

-

The Saltire Mosaic

Find out more about the surviving mosaic at North Leigh and explore details of its design.

-

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan of North Leigh Roman Villa to see how its buildings developed over time.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

-

EXPLORE ROMAN BRITAIN

Browse our articles on the Romans to discover the impact and legacy of the Roman era on Britain’s landscape, buildings, life and culture.

-

ROMAN BATHING

Bathing was central to Roman life. Discover what Roman bath-houses can tell us about the culture and people of Roman Britain.

-

THE ROMAN INVASION OF BRITAIN

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

Further reading

SR Cosh and DS Neal, Roman Mosaics of Britain, vol IV: Western Britain, 244–57 (London, 2010)

J Creighton and M Allen, ‘Fluxgate gradiometry survey at North Leigh Roman Villa, Oxfordshire’, Britannia, 48 (2017), 279–87 (subscription required; accessed 5 Sept 2024)

Guy de la Bédoyère, The Buildings of Roman Britain (Stroud, 2001)

P Ellis, ‘North Leigh Roman Villa, Oxfordshire: a report on excavation and recording in the 1970s’, Britannia, 30 (1999), 199–245 (subscription required; accessed 5 Sept 2024)

H Hakewill, An Account of the Roman Villa Discovered at Northleigh, Oxfordshire in the years 1813, 1814, 1815, 1816 (London, 1826)

J Percival, The Roman Villa (London, 1976)

DR Wilson, ‘The North Leigh Roman Villa: its plan reviewed’, Britannia, 35 (2004), 77–113 (subscription required; accessed 5 Sept 2024)