Henry VIII and the invasion threat

Portland Castle formed part of Henry VIII’s nationwide strengthening of England’s defences, during which new fortifications were built at important ports and anchorages along the east and south coasts. The threat that prompted their construction came from continental Europe, where two powerful rulers, Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (reigned 1519–58) and Francis I of France (1515–47), were being urged to invade England by Pope Paul III (1536–49).

The unlikely alliance between the Empire and France – whose relations were usually strained or hostile – was partly a response to Henry VIII’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon (Charles V’s aunt) in 1533 and the Act of Supremacy in 1534, which made Henry VIII head of the church in England. He took over church property and destroyed all monasteries, taking their resources. Pope Paul, incensed by the loss of the English church from the Catholic family, brokered the Franco-Imperial alliance in 1538–9.

The combined armies and navies of France and the Empire were formidable, though how real the invasion threat was is debatable. In any case, the English government took rapid action. In February 1539, the Privy Council enacted ‘the device of the king’, a plan to improve the nation’s defences. ‘Expert men’ were sent around England and Wales to recommend defensive measures. The most powerful king’s man in the west, Sir John Russell, reported on Portland.

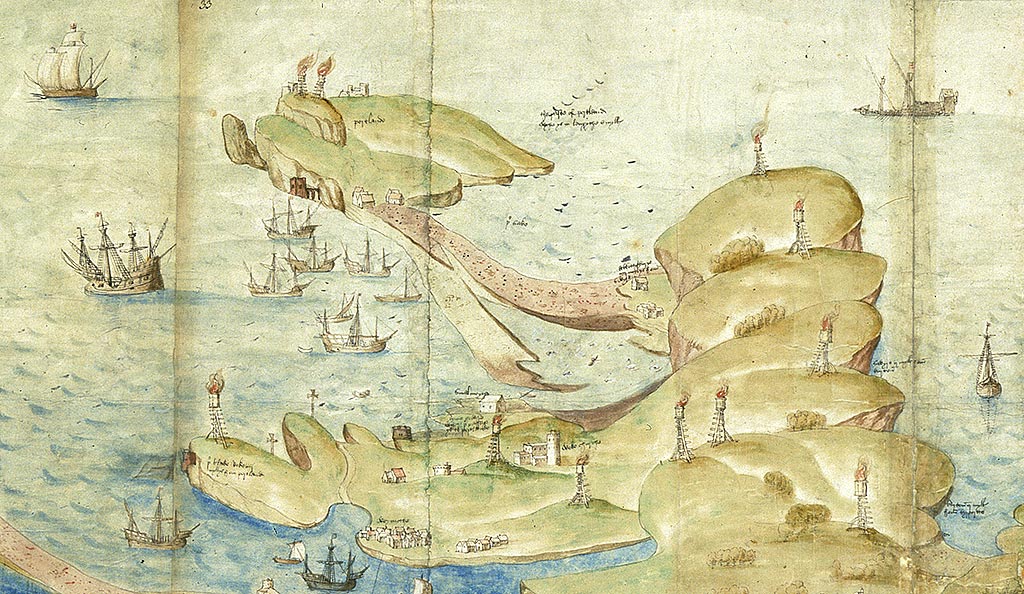

Defending Portland Roads, 1539–41

Portland Roads was an important deep-water anchorage, a large expanse of sea sheltered from the worst weather conditions by the Isle of Portland and the natural barrier of Hamm Beach and Chesil Beach linking it to the mainland. As such, it was a valuable refuge for English ships but also an attractive target for an enemy, where they might land troops and supplies for a military campaign inland.

Henry’s builders provided two forts to defend Portland Roads: Portland Castle on its southern shore, close to the eastern end of Chesil Beach, and Sandsfoot Castle, on a low cliff to the north-west towards Weymouth. Together, the castles’ guns could cross their fire at ships in the anchorage.

Unlike other ‘device castles’ built as part of this campaign (Sandown, Deal, Walmer, Sandgate, Calshot, Camber, Hurst, St Mawes and Pendennis), Portland was not built to a circular design for all-round defence. Its main gun battery, originally of two storeys, is a segment of a circle facing seaward. At the rear is a chevron-shaped three-storey ‘keep’, which provided accommodation and storage. Its roof originally formed an open-air platform for a third tier of guns.

Originally the castle may also have been provided with landward-facing earthwork defences. However, the surviving stone wall and external moat, forming an enclosed castle yard, were built in the mid-1620s. The entrance to the yard was across a drawbridge and through an L-shaped lodge in the south-west corner, probably a porter’s lodging and guard house. In 1716 this building housed the captain’s brewhouse, a small stable and the quarters for a sutler, who sold food to the garrison. Today, after many alterations, it survives as one range and is known as the Captain’s House.

The castle and its garrison in the 16th century

The garrisons of the device castles were small and intended to provide peacetime care and maintenance, to be a visible expression of Henry VIII’s government and to keep watch. In wartime, they were joined by professional soldiers and local part-time soldiers to form a garrison large enough to work the guns and defend the castle against attack.

The first captain of Portland Castle, Thomas Mervin, had only four gunners and two other men, but in 1596 captain Carew Ralegh commanded 18 men, a porter (for the castle), an under-porter (for the castle yard), a master gunner, five gunners and ten soldiers. By 1636 this had been reduced to a captain and 11 soldiers/gunners.

In 1547 the castle was well armed with 15 guns mounted on new wooden carriages, including four large weapons capable of long-range fire. There was a small store of 23 longbows, 24 bills (a stabbing and chopping weapon on a long pole) and 14 pikes (a spear-like weapon on a very long pole, used for thrusting, not throwing).

However, after 1547 the castle was neglected. In 1574 the captain, John Leweston, reported that all the guns were not fit for service. No repairs were made until the 1580s, during the early stages of the war with Spain (1585–1604).

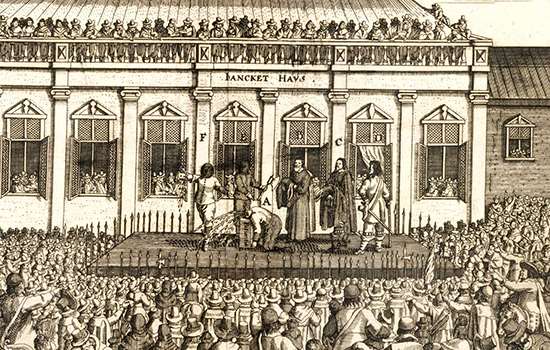

The English Civil Wars and the 17th century

By 1623, when a military engineer surveyed the castle, he found that another period of neglect had left many of the wooden gun carriages and the upper storey of the seaward battery in a state of decay. Repairs soon followed and the castle was well maintained during the First English Civil War (1642–6), when the Isle of Portland was a Royalist stronghold. The garrison created a larger defended area, with new earthwork defences beyond the castle yard.

A Parliamentary force took the castle in 1642 but it was recaptured in 1643 by Royalists disguised as friendly troops. In a four-month siege in 1644, this garrison held firm. The following year its soldiers fought at Weymouth and Melcombe but they lost the bloody struggle for control of Weymouth. In 1646 the war turned in favour of Parliament, and Royalist forces in the west were defeated. Without hope of aid and supplies, the Portland soldiers surrendered and were permitted to leave unharmed.

After the Civil War, the leaders of the Commonwealth (1649–60) maintained a garrison of about 60 soldiers to watch over Portland and its anchorage. They were reinforced and on high alert when about 160 warships of the English and Dutch fleets fought a titanic clash off Portland, in February 1653, during the First Dutch War (1652–4). The battle ended with a Dutch retreat and the garrison was not called on to fight.

Following the Restoration of Charles II (reigned 1660–85), the castle was well armed with16 big guns and was repaired following a survey in 1665. By this time, two stone platforms for extra guns – the east and west batteries – had been added on either side of the castle. These were capable of supporting another five guns firing directly into the anchorage.

Portland and piracy

The Dorset coast was frequented by pirates and smugglers, and Portland Roads was a pirate lair. In the 1550s the captain of Portland Castle, George Strangways, allowed his brother Henry to store stolen goods in the castle, taken during piratical activities in the Channel.

In 1607, Viscount Bindon, Lord Lieutenant of Dorset and Admiral of the Coast, wrote to the Privy Council in London:

Portland Castle is the only place of refuge, and a very nursery, accounted these many years for giving succour to all pirates.

He had intelligence that pirates were being supplied, fed and entertained in the castle, that the garrison went aboard pirate ships and that pirates had been allowed free rein, stealing about 50 sheep from the islanders.

Image: Henry Strangways, a pirate who used Portland Castle in the 1550s

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The 18th century

In 1702 Charles Langrish, magistrate, wrote that the castle was ‘in a very dangerous condition’ after another period of neglect:

there is not a grain of powder in the Castle and the gunner … was forced the Sunday before to quit the Castle and shift for himself. He has left in possession of the sutler’s office that is in the Castle yard, a miserable poor fellow that sweeps chimneys for his living, and two porters … which is the only garrison.

Things were no better in April 1715, when an Ordnance engineer, Colonel Christian Lilly, surveyed the castle and made a list of defects, noting that all its guns were not serviceable. Comprehensive repairs followed quickly, with new floors; doors and windows repaired; lead roofs stripped, recast and relaid; battlements and gun platforms fixed; and alterations made to the lodge. The number of guns was reduced to seven but in 1735 those were replaced by eight more powerful guns.

The castle’s main role throughout the 18th century was to defend merchant ships in the anchorage against privateers and pirates. A master gunner and two assistants looked after the guns, but by 1777 the garrison comprised only the captain (often absent), the master gunner, a gunner and two porters. This remained unchanged during the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1802) and Napoleonic Wars (1803–15), though over a hundred local part-time volunteers were on hand to help defend the castle and operate its 14 formidable heavy guns.

Despite the contemporary fear of a French invasion, the only actual invasion was one by a Royal Navy press gang that landed at the castle in 1803 and proceeded to Chiswell village to force men into the Navy against their will. A fight broke out: three local men were shot dead and a woman died later from her wounds.

The Mannings and the master gunner

In 1816, a year after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the castle was militarily redundant and the Board of Ordnance leased it to a local clergyman, the Reverend John Manning, as a domestic residence. However, the Board retained the lodge for its master gunner, along with a gunpowder magazine and storeroom in the castle. When the Reverend Manning died in 1826 his son, Captain Charles Manning, took on the castle until his death in 1869.

The Mannings transformed the castle into an elegant home. The castle porch and the heavy iron-studded doors date from this time, though the Mannings’ fine wood-panelled, plastered and decorated interiors have since been stripped out. The appearance of the lodge, now the Captain’s House, is due to Captain Manning, whose alterations in 1839 and 1858–9 produced its fashionable mock castellated facades. During his father’s time the garden was extended, landscaped and surrounded by new crenellated walls to match the architecture of the castle and lodge.

The army, navy and air force, 1869–1980

After Captain Manning, the castle and lodge reverted to government control as a comfortable residence for army officers serving nearby at the Verne Citadel. The Verne was built between 1857 and 1869 to defend the new Portland Harbour, whose breakwaters were built in 1849–72 and 1893–1906.

At the start of the First World War in 1914, Portland Castle became an arms and ammunition store. In September 1916 the Royal Navy took it over for HMS Sarepta, a shore base for floatplanes involved in the hunt for German U-boats in the English Channel. The Royal Air Force operated it from April 1918 until its closure in August 1919. The seaplane hangars and launch ramps stood west of the castle, but buildings erected in the castle yard and grounds included a bath house, latrines, a mess hut and a recreation hut.

From 1920 until 1980 the castle was used mainly by the Royal Navy’s HMS Osprey, an anti-submarine warfare training base. However, during the Second World War it was occupied intermittently, notably by soldiers of the Welsh Regiment in 1941, and in the build-up to D-Day in 1944. The Women’s Royal Naval Service occupied the Captain’s House throughout the war.

The castle was opened as a historic attraction in 1955 while the Captain’s House, spruced up in 1948, served as the residence for the senior officer of HMS Osprey until 1999. This, together with the gardens and courtyard, is now also open to visitors.

By Paul Pattison

Related content

-

Visit Portland Castle

Watching over a harbour full of history.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of the castle to see how its buildings developed over time.

-

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.