Norman Gaudie (1888–1955)

Norman Gaudie was called up soon after conscription was introduced in 1916. At the time, he was a clerk in the accounts department of the Eastern Railway, Newcastle, and reserve centre forward for Sunderland Football Club. A devout Congregationalist, he believed that any participation in the war effort would be a denial of his faith.

In early March 1916 he applied for total exemption from military service on religious grounds. He was granted exemption from combatant roles only, and just over a month later was arrested and handed over to the military after failing to report for non-combatant service. His clothes were forcibly removed when he resisted medical examination in Sunderland, and at Newcastle barracks he was made to wear khaki before being sent to the Non-Combatant Corps at Richmond Castle.

Once there, Gaudie spent several periods in detention for continuing to refuse orders. Yet despite his ordeal, his wartime diaries record moments of solidarity and optimism. He thrived on debates with other conscientious objectors, sang hymns, read, recited the Bible and even managed to play chess on a pocket chessboard. His friend Bert Brocklesby (see below) drew a likeness of Gaudie’s mother on their cell wall, copied from a photograph he kept in a secret pocket.

Just over a month after arriving, Gaudie became one of 16 men from Richmond sent to France, court martialled and sentenced to death. Their sentences were immediately reduced to ten years’ penal servitude. Back in Britain, Gaudie spent the rest of the war in civil prisons and work centres in Winchester, Dyce (near Aberdeen), Wakefield, Armley, Leeds and Maidstone.

After his early release in 1919, like many conscientious objectors Gaudie struggled to find work and acceptance in his local community. This even extended to his passion, sport – the chairman of his local cricket club objected to him playing.

John Hubert Brocklesby (1889–1962)

On 29 February 1916 John Hubert (Bert) Brocklesby, a schoolteacher from Conisbrough, South Yorkshire, confidently explained to the Doncaster Military Tribunal that war contravened the Sixth Commandment in the Bible – ‘Thou shalt not kill’. Brought up as a Wesleyan Methodist in a family of lay preachers, Brocklesby was no stranger to expressing his beliefs.

Nonetheless, the tribunal ordered him to join the newly formed Non-Combatant Corps. To Brocklesby, taking part in its work – related to the war effort, but not actual combat – was just as impossible as fighting, and he refused to enlist. It was only after being arrested that he eventually made his way to Richmond Castle, a base for the Non-Combatant Corps.

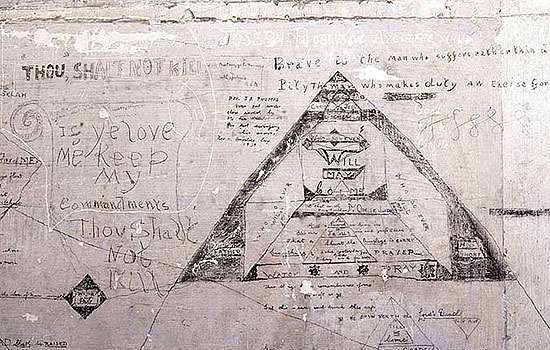

At Richmond he repeatedly disobeyed orders and spent several periods of confinement in the cells. While detained he sketched and wrote many graffiti on the cell walls.

Before long, Brocklesby was sent to France. Determined to ensure his family and supporters knew his location, he cleverly doctored a field postcard to read: ‘I am being sent to … b … ou … long’ [Boulogne]. As a result, his brother Phillip, an officer in the army, was able to visit him.

On his return to Britain, Brocklesby was held at Winchester prison before being sent to quarry stone at Dyce Camp, near Aberdeen. On hearing the stone would be used on a military road, he refused to continue working and served the rest of his sentence in civil prisons.

Although his family welcomed him with open arms when he arrived home after the war, he ‘was surprised to find how bitter local feeling was against me; it seemed much worse than in 1916’. He soon left Conisbrough and travelled to Austria and Russia with the Friends’ War Victims Relief Committee, to help victims of war.

See more of Brocklesby’s GraffitiAlfred Myers (1884–1948)

Alfred Myers came from a large family in East Cleveland and before the war worked with two of his brothers in the ironstone mines. A member of the Independent Labour Party and a devout Wesleyan Methodist, he played a key role in his local community. He was a tenor in the Wesleyan Carlin How choir, a Sunday school superintendent and trustee of the local church.

At his hearing for exemption from compulsory military service, Myers asserted his belief in an international brotherhood of man, and stated that he ‘could not conscientiously kill, nor assist in killing’. But like so many others he was only granted exemption from combatant service and was sent to the Non-Combatant Corps at Richmond Castle.

In the cells at Richmond, Myers’s tenor voice was put to good use. With two other conscientious objectors, Brocklesby and Gaudie, he sang the hymn ‘Nearer My God to Thee’ in three-part harmony. Myers’s performance wasn’t as perfect as the other prisoners hoped, however – they had to bang on the cell floor to keep him in time.

Following his ordeal with the rest of the Richmond Sixteen in France, Myers was sent first to Dyce Camp, near Aberdeen, and then Maidstone prison. Others of the Richmond Sixteen were also there, and Myers worked alongside Brocklesby in the laundry.

On his release, the effects of imprisonment were evident. Brocklesby described in his memoirs how on their journey home ‘poor old Alfred … was suffering from an emotional or nervous reaction and felt unable to go further alone’.

Alfred Matthew Martlew (1894–1917)

A member of the No-Conscription Fellowship and the Independent Labour Party, Martlew was uncompromising in his stance against the war. But despite his protestations he was ordered to join the Non-Combatant Corps, and was one of the 16 men sent from Richmond to France in May 1916.

After returning to England, Martlew was imprisoned at Winchester before being offered a place on the Home Office Scheme. This gave ‘genuine’ and ‘sincere’ conscientious objectors the opportunity to undertake civilian work under civilian control as an alternative to time in prison. Martlew worked in the quarry at Dyce Camp, spinning at Wakefield Work Centre, West Yorkshire, and tree felling in Dalswinton, Dumfries. But like many other conscientious objectors he questioned whether the work he was performing was still contributing, if indirectly, to the war effort.

In 1917 Martlew went missing from his Home Office Scheme post and travelled to York where, before the war, he had been a ledger clerk at Rowntrees Cocoa works. There he met his fiancée, Annie Leeman. He gave her his money, watch and other possessions, and told her he intended to hand himself in to the police authorities.

This was their last meeting. Just over a week later Martlew’s body was found in the River Ouse at Bishopthorpe. Although the inquest into his death returned the unresolved verdict of ‘found drowned’, the coroner thought it likely that he had taken his own life.

Clarence Hall (1896–1973)

On 29 May 1916 Clarence Hall wrote ‘Sent to France with 17’ on his cell wall at Richmond Castle. Rumours had spread that the 2nd Northern Non-Combatant Corps, to which Clarence and his brother Stafford were attached, were preparing to go to France and that men held in the cells would be joining them. Hall had just enough time to inscribe his name, membership of the International Bible Students Association (IBSA), and dates of detention on his cell wall.

Before the war Hall had been a clerk at a joining and contracting business. In 1916, after having his application for total exemption from military service refused, he was ordered to join the Non-Combatant Corps. He refused to sign his army papers, and was forced into khaki at Fulford Barracks, York. Later he was given seven days’ detention in the cells at Richmond Castle. Despite the dire circumstances, Hall used his confinement to discuss religion and theology with other conscientious objectors.

On his return from France he was imprisoned at Winchester before undertaking work at Dyce Camp, Wakefield and Knutsford work centres. He had a succession of jobs after the war including working for a paper manufacturer and as a sales representative. When war broke out again in 1939, he undertook fireguard duties in Hull.

Charles Herbert Senior (1887–1977)

From the outbreak of the First World War, Senior, a carpenter and cabinet maker from Leeds, was active in the IBSA in denouncing Christian involvement in the conflict. At his hearing for exemption from compulsory service, he defended his position ‘illustrating almost every sentence with chapter and verse’. Nonetheless, he was ordered to join the Non-Combatant Corps.

When Senior failed to appear for training he was arrested. He refused to sign papers, undergo medical examination or follow orders. Sent to the Non-Combatant Corps at Richmond Castle with four other men from Leeds, he was soon put in the cells. At Richmond he spoke out about the ill-treatment of other conscientious objectors there, and even swapped cells with another CO who was afraid of the room he had been placed in.

When sent to France with the rest of the Richmond Sixteen, Senior was the first to refuse the order to move what they believed to be ammunition that led to their trial and Field General Court Martial. As he explained after the war:

To me there was no difference in principle in unloading shells … and putting that shell into a gun to be fired for the killing of men. It was all part of the same process.

After returning to England, Senior was sent to Winchester prison. There he kept in touch with other conscientious objectors by writing notes on toilet roll, using a pencil kept in a secret pocket his sister had sewn inside his vest.

When Senior was eventually released, he became a Pilgrim or Travelling Overseer for the IBSA.

Read the story of the Richmond SixteenCharles Rowland Jackson (1895–1974)

‘Those with whom we have come in contact cannot understand our being so quiet and confident, when … the situation is so serious’, wrote 21-year-old Charles Rowland Jackson from France in June 1916. One week earlier he, with the rest of the Richmond Sixteen, had been sentenced to death, a sentence which was immediately commuted to ten years’ penal servitude.

Secretary for the Leeds branch of the IBSA, Jackson’s confidence was rooted in his Christian beliefs. As he explained, ‘we have learned so much of the Lord’s care during the past few weeks that we are prepared to leave all in His Hands’.

Before the war Jackson was a clerk at a Leeds wool merchant and, like his father, became a conscientious objector. While his father was exempted from service on condition that he completed work of national importance, Jackson was sent to join the Non-Combatant Corps at Richmond Castle.

Soon after arriving there Jackson was detained for 11 days while awaiting trial for ‘insubordinate language’. He spent 48 hours in solitary confinement on a punishment diet of bread and when finally sentenced, was given six months’ imprisonment. He only served three days before being sent to France with the rest of the Richmond Sixteen.

By 5 July 1916 Jackson was back in England and imprisoned at Winchester before being granted civilian work, first at Dyce Camp and later at Longside, Warwick and Dartmoor.

After his release Jackson married and his family later emigrated to Australlia. At some point he left the IBSA, but he remained a Bible Student for the rest of his life.

William Law (1891– ) and Herbert Law (1892– )

The Law brothers were born in Melbourne, Australia, but moved to Yorkshire as children. William Edwin (Billy) followed in his father’s footsteps and became a house painter. His younger brother, Herbert George (Bert), was a clerk at a share brokers.

On 8 May 1916 the two brothers were handed over to the military authorities after failing to report to the Non-Combatant Corps. Both were members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and No-Conscription Fellowship. Their applications for total exemption from military service were refused both by their local military service tribunal and at a subsequent appeal tribunal.

Soon after receiving his call-up notice for non-combatant service, Bert married Isobel Gertrude Elaine. Perhaps he anticipated that he would be sent away for some time for his objection. If so, his premonition was correct.

The brothers were sent to Richmond Castle and later, with the rest of the Richmond Sixteen, to France. On arrival at Richmond they submitted to a medical examination but refused rations and were confined to the cells. It was not until over four days later that Norman Gaudie, another conscientious objector, managed to give them some food to tide them over. In Gaudie’s war diaries he describes how he felt inspired by their presence.

The brothers spent the last years of the war in civil prisons and work centres. They later returned with their families to their birth country, Australia, and plied the family trade, painting and decorating.

Richard Lewis Barry (1890–1949)

In March 1916, 26-year-old Richard Lewis Barry stood before six members of the Long Eaton Urban District Tribunal held at Zion Hall, Long Eaton, Derbyshire, claiming exemption from conscription on the grounds of his socialist views.

All six tribunal members listening to Barry’s case were lace manufacturers. Barry worked as a twisthand in the Frank T Sutton Lace Manufacturing business at Cavendish Mill on Bennett Street, Long Eaton. Working mostly with cotton, twisthands were so called because they made a high quality twisted lace. They were highly skilled and could earn a good wage.

When both the local and appeal tribunals refused his claim, Barry protested about the unfair administration of the Military Service Act. Local newspapers recorded his articulate grievances.

After failing to present himself when summoned, Barry was handed over to the military authorities. He spent 56 days in detention at Normanton Barracks, Derby, and Wakefield Military Prison, before finding himself in Richmond Castle for refusing to go on parade. There, he wrote many inscriptions on the cell walls. Court martialled three more times in the course of the war, Barry was eventually released in April 1919.

See more graffiti by BarryPercy Fawcett Goldsbrough (1896–1988)

On the wall of one of the first-floor cells at Richmond Castle is one of two inscriptions by Percy Fawcett Goldsbrough, a 20-year-old brass moulder from Mirfield in Yorkshire. It records how, on 11 August 1916, he was put in the cells for ‘refusing to be made into a soldier’.

Goldsbrough was a member of the Huddersfield branch of the British Socialist Party and like a number of other socialists refused to take any part in the war. This was a war he believed was caused by the greed of ‘diplomats & the money lords’ and which had nothing to do with the working classes.

When he was granted exemption from combatant service only, Goldsbrough did not follow orders to join the Non-Combatant Corps. It was only after being arrested as an absentee that he made his way to Richmond Castle.

His first two days at Richmond were spent in the cells. Less than a week later he was court martialled, sentenced to 112 days’ imprisonment for refusing orders, and transferred to Durham civil prison. While there he wrote a poem explaining his beliefs:

We care not how their evil threats

Their punishments still stand

We will not lend our aid to kill

Men of another land.

After the war Goldsbrough returned to his job as a brass moulder and, as soon as he could, married Edith Berry at the Wesleyan Chapel in Sheepridge, Huddersfield.

Top image: conscientious objectors, including some of the Richmond Sixteen, at Dyce Camp, near Aberdeen, in 1916

© Peace Pledge Union Archives (www.menwhosaidno.org)