The Need for more men

By the summer of 1915 it was becoming apparent that the enthusiasm to fight for ‘King and Country’, so much in evidence in the autumn of 1914, had begun to wane. The voluntary system could no longer produce enough young men to fill the gaps made in the British army by the relentless killing on the Western Front, and the government began to move towards compulsion.

In January and May 1916 the Military Service Acts introduced compulsory military service, known as conscription, first for single men and then for all men between the ages of 18 and 40.

The Tribunal System

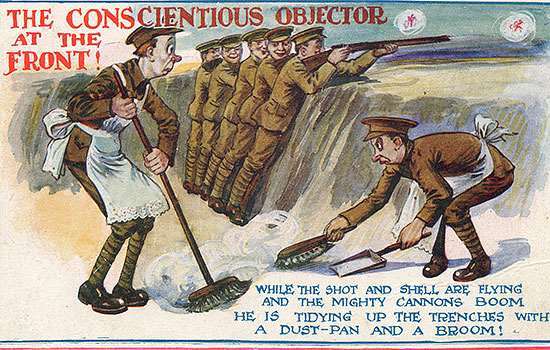

Not everyone in Britain supported the war, however, and not everyone welcomed conscription. A number of religious and political groups had been campaigning against the war since 1914. Yet conscription presented a new challenge. The Military Service Acts put in place a national system of local tribunals to which conscripts could appeal for exemption from service. Among the grounds for exemption, along with hardship, illness, education and the essential nature of their work, men could also claim on grounds of a conscientious objection to military service.

Applicants for exemption had to argue their case in front of a tribunal made up of prominent local men and a military representative. After an often brief and sometimes hostile round of questioning, tribunal members had to decide whether applicants were ‘genuine’ or motivated by cowardice.

By the end of the war more than 20,000 had applied for exemption as conscientious objectors (COs). For some this meant a total rejection of all that the war meant. Even the opportunity to do their bit as non-combatants in the specially created Non-Combatant Corps (NCC) was asking too much, and they resisted.

The Northern Non-Combatant Corps

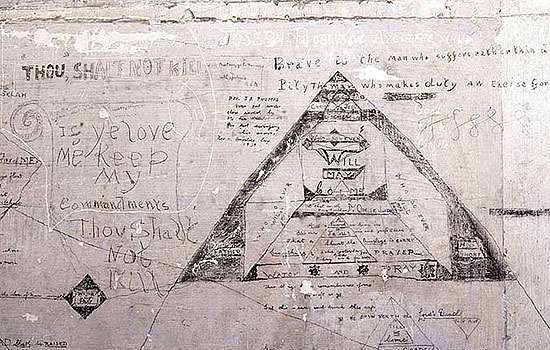

In the spring of 1916 Richmond Castle, traditional home of the Green Howards, also became the depot for the northern companies of the NCC. Several hundred COs found themselves based there. Many of them accepted military discipline and obeyed their orders, but others did not.

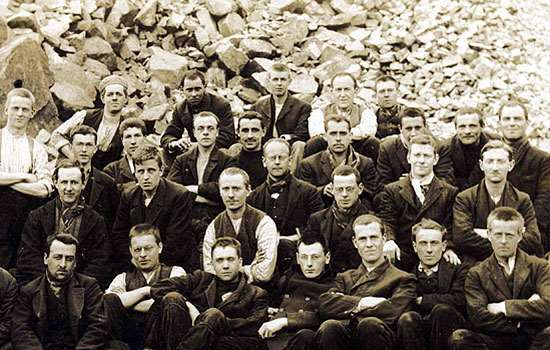

By May that year, the army was sending companies of NCC men to France, from camps across England and Wales, in the expectation that they would do non-combatant work behind the lines. Whether by accident or design, among them were 35 men who were already refusing to obey orders. They included 16 young men from the north of England, 13 of them from Yorkshire, who have become known as the Richmond Sixteen. Their transportation to France, trial and sentencing have become notorious in the history of conscientious objection.

READ THE STORY OF THE RICHMOND SIXTEENLater Conscientious Objectors at Richmond Castle

Over the next two and a half years Richmond Castle saw many more disobedient COs. At least another 190 were court martialled there, some of them several times. For most, it was the first step towards a war spent in prison and work centres at Wakefield, Knutsford, Warwick and Dartmoor, and on work schemes across the country, whether building reservoirs in Wales or road-building in the Scottish Highlands. This work was part of the Home Office Scheme which, from August 1916, offered COs in prison ‘work of national importance under civil control’ as opposed to time in prisons or guardrooms.

For a hard core of 20 Richmond men in a national total of more than 1,600, it was the beginning of a much more difficult experience. These men, known as absolutists, refused to have anything to do with any schemes for COs, arguing that to do so would be to accept the state’s right to direct their consciences. For them the war was a continuing round of prison, court martial, and back to prison again, occasionally interspersed with hunger strikes and force-feeding.

Legacy: The Anti-War Movement

Beyond Richmond, courts martial, prisons and work camps, the anti-war movement took strength from these COs’ experiences.

While it did not succeed in ending the war, in the post-war world the men and women who had campaigned for COs and against the fighting continued to contribute to British politics. Between 1919 and 1929 at least 145 different constituencies selected men and women as Parliamentary candidates from the wartime anti-war movement. There were 68 in 1923, of whom 34 were elected – 14 of them former COs.

Cyril Pearce, Honorary Research Fellow, University of Leeds

Top image: Conscientious objectors building a road in East Anglia in 1916

© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans