The Wall at Sewingshields

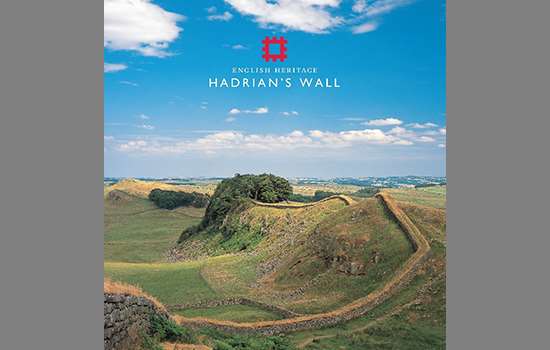

From Sewingshields Farm, the route of Hadrian’s Wall gradually climbs westwards for ¾ mile (1.2km) to higher ground, reaching a summit of 325 metres on Sewingshields Crags. It follows and exploits the natural defence formed by the Great Whin Sill. The route of the Wall is clear for most of this distance, and west of Sewingshields Farm several lengths of the Wall have been excavated and conserved.

The foundation here was made to carry the original planned Wall width of about 10 Roman feet (2.96 metres). But when the Wall was built, it was to a reduced width – often referred to as the narrow Wall – of around 8 Roman feet (2.37 metres).

Read more about building Hadrian’s WallSeveral ‘centurial stones’ have been found in the area, recording the names of soldiers and their military units responsible for building sections of Hadrian’s Wall. These include two inscribed LEG II AUG (the Second Legion Augusta) and others recording the centurions Caecilius Proclus, Maximus, Gellius Philippus, and Florianus. Each centurion commanded 80 men.

The work to uncover and consolidate the remains at Sewingshields took place in several campaigns, the first in the 1930s to expose the Wall, then in 1958 when turret 35a was excavated, in 1975–6 to expose more of the Wall, and finally from 1978, when work to reveal milecastle 35 (Sewingshields) began.

Some 52 metres east of the milecastle the excavators found a burial, contained within a grave, or cist, made of stone slabs and built against Hadrian’s Wall. The grave contained the remains of an adult, probably male, aged 30–40 years. With no finds, the burial could not be dated, but it is likely to be Roman.

Sewingshields Milecastle

Milecastles, built about 1 Roman mile (1.48km) apart along the Wall, usually incorporated gateways that allowed access into and out of the Roman province of Britannia. Sewingshields Milecastle, unusually, does not have a north gate through the frontier, presumably because the 30-metre high crags immediately outside made one impractical. It is just possible that there was an entrance here which was later removed, but no trace remained when the site was excavated.

The milecastle has extensive views to north and south and has its long axis parallel to the Wall. It sits in a good stretch of Wall which has been revealed and conserved for 320 metres to the east and west.

Milecastles

Milecastles were part of the original design for Hadrian’s Wall before a major change of plan – to incorporate large forts on the Wall – was made part way through its construction.

In the original design, each milecastle protected a gateway through the Wall. We don’t know whether they were designed to allow soldiers to pass through and patrol to the north, or to check civilian movements in and out of the province, or perhaps both. Each milecastle probably had a small garrison of around eight soldiers living in a single barrack building, though some had two buildings capable of accommodating more, perhaps up to 32 soldiers. These larger garrisons may have been manned milecastles in more vulnerable locations.

Milecastles were small rectangular defended enclosures, with walls between 15 and 18 metres along one internal side and 17–23 metres on the other. Some have their longer axis parallel to Hadrian’s Wall (short axis type) while others have it perpendicular (long axis type). Variation in detail includes the form of the gateways and the number and type of internal buildings. There were usually gates in both the north and south walls, the former probably surmounted by towers. There may also have been buildings outside the walls, although this has not been widely studied.

The term ‘milecastle’ was first used in the early 18th century. In the late 19th century, the milecastles were numbered from 1 to 80, beginning at Wallsend at the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall. Many have been excavated but only six have substantial visible remains. English Heritage cares for four of these: Sewingshields (35), Cawfields (42), Poltross Burn (48) and Harrows Scar (49), plus one other at Grindon (34), where there are no remains above ground.

The milecastle’s development

Excavations at milecastle 35 in the 1970s uncovered a complicated sequence of building and rebuilding inside the milecastle over more than 250 years.

Its long history began in the AD 120s, when the enclosed area contained one small building – probably a barracks – on the east side of a central roadway of stone chippings. This building was remodelled once, and then replaced by a new one in the early 3rd century. At that time a second, much larger building was added west of the roadway. Both buildings contained hearths, and an oven was placed outside the milecastle in the angle formed by its east wall and Hadrian’s Wall. The two buildings, perhaps for a larger garrison, had a long life extending into the 4th century.

Sometime in the 4th century the two old buildings were replaced by less well-built structures and another oven was added, this time inside the milecastle. These buildings were associated with small-scale metalworking in iron and bronze, indicating a very different use from that of earlier times.

Life at the milecastle

Many small objects recovered during excavations provide glimpses of everyday life at the milecastle. These include pottery sherds from fine and coarse vessels, parts of six stone hand-mills for grinding cereals into flour, a reaping hook, a key, whetstones, and fragments of glass from bottles, drinking vessels and about 15 fragments of window glass. The latter, dated to the 2nd century, reveals the amount of care taken to make the building’s interior comfortable.

A large number of military finds of iron included eight spearheads, an artillery bolthead, a dagger, a shield boss, two arrowheads and twelve knives. There were also objects relating to personal adornment such as a jet finger ring, jet beads and an armlet, while two stone gaming boards give us an idea of how the garrison passed the time.

Medieval settlement

Over 850 years later, the site was re-occupied by a settlement that flourished from the mid 13th to early 15th centuries. By this time, erosion and stone robbing had reduced the milecastle walls to tumbled mounds. Three medieval buildings, added at different times, were discovered here during excavation. They were probably outliers of the medieval manor of Sewingshields, which included a fortified tower house about 800 metres to the east.

The buildings were of the ‘longhouse’ type that combined a living space and an animal byre (shed). They may only have been occupied periodically or seasonally in the spring and summer, as no constructed floors or hearths were found inside them during excavation. Such buildings had low rubble walls and roofs of turf or thatch. Small stone platforms outside them were possibly ‘stack stands’ for drying hay.

Around the settlement are the tumbled remains of an extensive system of walled fields that the settlement may have served. They may have included the ‘Wall Field’ which is recorded in contemporary medieval documents.

The turrets of Hadrian’s Wall

In the original design for Hadrian’s Wall, about 160 turrets were built two to every Roman mile along it. They provided lookout positions for small groups of soldiers to monitor people’s movements north of the Wall, and shelter and basic facilities for the men on duty. Two turrets were positioned between each pair of milecastles, which probably provided the troops for duty at the turrets.

Sometime after work on the Wall began, and well before its completion, a decision was taken to build large forts such as Chesters and Housesteads to hold garrisons of 500 and sometimes 1,000 soldiers. By this time many turrets had been begun or completed, and some were demolished to make way for the forts.

Each turret was about 6 metres square externally, its interior space recessed into the thickness of the Wall and entered through a door in the south wall. Turrets were probably two or three storeys high, but their full height and design above the ground floor is uncertain. They may have had open observation platforms with parapets, or pitched roofs covered with tiles, thatch or shingles. The evidence differs from one turret to another, and roof construction may have varied over time and by location.

Excavations at many turrets have produced evidence of how soldiers used them. Pottery, cooking utensils and items such as gaming counters show that small groups of soldiers routinely cooked, ate, relaxed and probably slept in turrets during their periods of duty on the Wall.

Turrets are numbered in relation to milecastles: each pair takes the number of the nearest milecastle to the east, ‘a’ for the eastern turret and ‘b’ for the western one.

Sewingshields Turret (35a)

Turret 35a’s dramatic location on Sewingshields Crags, close to the edge of the Great Whin Sill, was a perfect platform for observing a wide tract of territory to the north.

Today, it survives only just above foundation level, in a well-preserved stretch of Wall that is exposed intermittently for over 600 metres along the edge of Sewingshields Crags. Like other turrets on the Wall, it was built with short ‘wing walls’ to either side, before the Wall itself (other than the foundation). The wing walls are just under 10 Roman feet (3 metres) wide. By the time the main body of the Wall was built up to the turret, it was being made narrower, so parts of the wing walls where they join the Wall were left exposed. They are still visible today.

Excavations at turret 35a in 1947 and 1958 revealed that its ground floor was formed of clay with cobbles and rough flagstones, laid directly over a layer of stone chippings left by the turret builders. There was a hearth placed centrally against the east wall and a small, flat-bottomed, recessed ‘box’, measuring 0.3 by 0.35 metres and formed of two upright stones, in the south-east corner.

Objects found here, such as pottery sherds, including amphorae (large storage jars), an iron knife blade, a bronze wheel-shaped brooch and part of a fine bronze cup, provide evidence of occupation, mostly dating to the mid 2nd century,

Turret 35a had a relatively short life, perhaps around 80 years. It was one of several turrets demolished in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD when plans for the Wall were modified. The Wall was rebuilt over the turret foundations, and this can be seen today where the turret interior, originally recessed into the Wall, was infilled with masonry to form its rear face. The doorway to the turret, towards the eastern end of the south wall, had been blocked with masonry sometime before demolition.

Grindon Turret (34a)

Turret 34a can be seen 250 metres east of the farm buildings at Sewing Shields, on a low ridge overlooking the wet upland area of Fozy Moss to the north. Its short wing walls demonstrate its construction before the main Wall joined it.

Excavations in 1971 revealed that the turret’s ground floor was formed of clay and mortar, on which were three hearths, used by the soldiers for cooking and keeping warm. The door threshold stone had a circular socket for a pivot, showing that the door opened outwards. A few discarded items, such as pottery sherds (including amphorae), an iron knife blade and an iron spearhead were also found, all from the mid 2nd century AD.

Like turret 35a, this turret had a short life. It was demolished in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, when several other turrets were also being abandoned as part of the change of plan for Hadrian’s Wall. Demolition left just the lower walls standing, and the Wall was rebuilt over the turret foundations. Its south face can be seen today.

By Paul Pattison

The Wall nearby

The walk along Hadrian’s Wall westwards from Sewingshields is spectacular for 1.7 miles (2.7km), affording panoramic views from the edge of the Great Whin Sill. From the summit of Sewingshields Crags, the route eventually descends to the Knag Burn gate. Then the terrain rises again, and another conserved section of Wall resumes to meet what is regarded as the most impressive site along its entire length, Housesteads Roman Fort.

More about Hadrian’s Wall

-

Hadrian’s Wall: History and Stories

Discover the history and stories associated with Hadrian’s Wall, the north-western frontier of the Roman Empire.

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.

-

Buy the guidebook to Hadrian’s Wall

The English Heritage guidebook to the Wall provides maps, plans and tours of all the key sites, as well as a history of the Wall and its forts.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.