What is the tapestry?

The Bayeux Tapestry is world-famous today as the source of much of our understanding of the Norman Conquest. However, scholars only first identified the tapestry’s significance in 1729. It was discovered on display during the religious festival of relics at Bayeux Cathedral in Normandy. The tapestry still resides in the town in the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux.

There are many questions surrounding its origins that will probably remain unsolvable, continuing to provoke much speculation based upon little historical evidence. Even its name is misleading, as it is actually an embroidery, sewn onto fine linen. True tapestries are woven on a loom.

It measures nearly 70 metres long and is 50 centimetres tall. A narrative travels across the centre of the panels, telling the story of the Norman Conquest, with side narratives and decoration in the borders above and below. The main narrative is supported by text, which helps to identify the characters and scenes.

The tapestry would have originally been longer, as the last panels are missing. However, the majority survives and tells a sophisticated story. It is based around the justification for William the Conqueror’s claim to the English crown and his invasion and defeat of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Read more about the Battle of HastingsAn English Work

Although it is now on display in France, most historians agree that the embroidery is of English origin. This kind of needlework was later called Opus Anglicanum, or English work. It was internationally recognised as superior, and conferred élite status upon its patrons and owners.

The Norman historian William of Poitiers noted that ‘everyone attests to the fact that English Women are very skilled in needlecraft and gold embroidery’. In the Domesday survey of 1086, English needleworkers were specifically mentioned. One, Leofgyd, was wealthy enough to hold a moderate estate at Knook in Wiltshire because ‘she made and makes the gold fringe of the king and queen’.

Another clue to the tapestry’s English origins lies within the embroidered text. In places it contains Anglo-Saxon lettering and spelling. For example, in the section showing the death of Harold’s brother Gyrth, the Earl of East Anglia and Oxfordshire, Gyrth is spelt with a barred letter D, as used by the Anglo-Saxons.

In the margins

More subtly, some of the tapestry’s borders illustrate scenes from English fables, or moralising stories, which were unlikely to have been readable by Normans. One such story is ‘The Wolf and a Crane’, where a wolf has a bone stuck in its throat that is retrieved by a crane using its long beak.

Some of these fables act as commentaries on the main scenes of the tapestry. For example, ‘The Fox and the Crow’, where a crow drops the cheese it has stolen and a fox grabs it, is a moral about one thief stealing from another thief. It injects humour and a less than flattering commentary on the main scenes. This suggests a designer with an ambivalent attitude to the Normans.

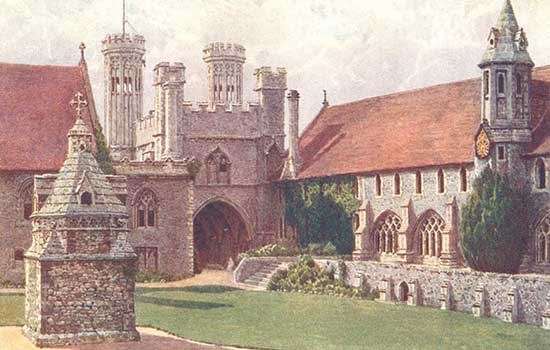

Why St Augustine’s Abbey?

St Augustine’s was the pre-eminent Benedictine abbey in England at the time of the tapestry’s creation. It had a reputation for fine manuscript illumination and a library that rivalled any in the kingdom. The other major school of illumination in England was at Winchester, but stylistically Winchester’s illustrations tended not to follow a narrative. Instead they highlighted significant figures as portraits, alongside the text.

In 1957, the art historian Francis Wormald identified the designer of the tapestry as having drawn inspiration from illuminated manuscripts produced at, or in the hands of, the religious houses in Canterbury in the 11th century. The majority of these were in the ownership of St Augustine’s Abbey.

In a 6th-century work known as the St Augustine’s Gospels, the figure of Christ at the Last Supper is strikingly similar in his pose to that of Bishop Odo when he is shown in the tapestry blessing the wine during the first meal after the Normans landed in England.

Likewise, models for the embroidery can be found in Canterbury’s late Anglo-Saxon copy of the 9th-century Utrecht Psalter. The most significant is a possible source for King Harold being struck in the eye by an arrow.

Finally, Wadard and Vital, two of the three named knights depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, were directly linked to St Augustine’s. Wadard served the abbey as a knight, and Vital was a member of the abbey’s confraternity (lay brotherhood). Both, as a result, are likely to have been buried at the abbey.

The Eyewitness

It is unlikely that just one person was involved in the making of the Bayeux Tapestry, but the style of the embroidery is consistent and has a sophisticated narrative, which points to a single designer.

Part of the tapestry shows the Breton campaign – a war between the Duchy of Normandy and the Duchy of Breton which took place in 1064. At that time, the senior monk at Mont Saint-Michel, an abbey in Normandy, was Scolland. He acted both as treasurer and head of the scriptorium (a group of monks skilled at creating manuscripts). After the Norman victory at Hastings, Scolland, along with others from the same monastery, went over to England. He was appointed by King William as Abbot of St Augustine’s, in 1070.

Historian Richard Gameson has proposed that the monk shown enthroned and pointing to the Abbey of Mont Saint-Michel in the tapestry is Abbot Scolland, which would mean he was an eye witness to the action shown. If so this would explain why several of the early scenes in the tapestry focus on the Breton campaign, despite it being less important than the Norman Conquest and Battle of Hastings.

The Anglo-Norman nature of the making of the tapestry and its narrative reflect Scolland’s own intellectual and cultural life and his complex political affiliations. Scolland’s authority at St Augustine’s Abbey, his close links to the Norman victors and his experience, especially as head of the important scriptorium of Mont Saint-Michel, make him the most likely candidate for designer of the tapestry.

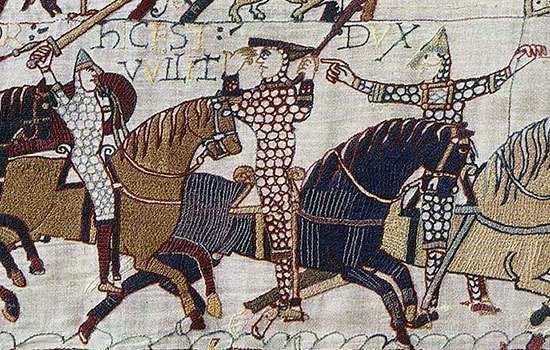

Top image: Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Vital, a knight who had direct links to St Augustine’s Abbey

© DeAgostini/Getty Images

Further Reading

Bernstein, DJ, The Mystery of the Bayeux Tapestry (Chicago, 1986)

Bloch, RH, ‘Animal fables, the Bayeux tapestry, and the making of the Anglo-Norman world’, Poetica, 37:3 (2005), 285–309

Bridgeford, A, 1066: The Hidden History of the Bayeux Tapestry (London and New York, 2004)

Carson Pastan, E, White, SD and Gilbert, K, The Bayeux Tapestry and Its Contexts: A Reassessment (Woodbridge, 2014)

Gameson, R (ed), The Study of the Bayeux Tapestry (Woodbridge, 1997)

Lewis, MJ, Owen-Crocker, GR and Terkla, D (eds), The Bayeux Tapestry New Approaches (Oxford, 2011)

Owen-Crocker, GR, ‘Reading the Bayeux Tapestry through Canterbury eyes’, The Bayeux Tapestry: Collected Papers (Farnham, 2012), 243–65

Wilson, D M, The Bayeux Tapestry (London, 1985)

Wormald, F, ‘Style and design’, in The Bayeux Tapestry, ed F Stenton (London, 1957), 25–36

Read more

-

History of St Augustine's Abbey

Learn about the fascinating history of St Augustine’s Abbey, from its monastic golden age to its later existence as home to a royal palace, poorhouse and school.

-

What happened at the Battle of Hastings?

At dawn on Saturday 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Read what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

1066 and the Norman Conquest

Find out much more about the events of 1066, and discover where to find some of the most spectacular castles and abbeys the Normans built across England.