Early Life in North Africa and Italy

Much of what we know of Hadrian (also known as Adrian) comes from the pages of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written at the monastery of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow in north-east England in the early 8th century.

According to Bede, Hadrian was ‘an African by birth’. Fluent in Greek and Latin, it is likely that he was from Cyrenaica. At the time of Hadrian’s birth in about 630–37, Cyrenaica was a province of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine Empire, on the southern shores of the Mediterranean in what is now Libya.

Christianity had deep roots in North Africa, with three early popes (Victor I, c.189–99; Miltiades, 311–14; Gelasius, 492–6) coming from the region. The influential theologian Tertullian (c.150–c.240) and St Augustine of Hippo (354–430) – one of the most important Christian authors of the Middle Ages – also had North African origins.

It is likely that the Arab invasion of Cyrenaica in 644–5 forced Hadrian to flee to Italy as a refugee. Bede tells us that Hadrian was ‘very learned in the Scriptures, experienced in ecclesiastical and monastic administration and a great scholar’, and that he became abbot of a monastery close to Naples.

Hadrian’s considerable talents did not go unnoticed, and there is some evidence to suggest that he became a trusted counsellor of the pope and the Byzantine Emperor, the two most important people in the Christian world.

Journey to Canterbury

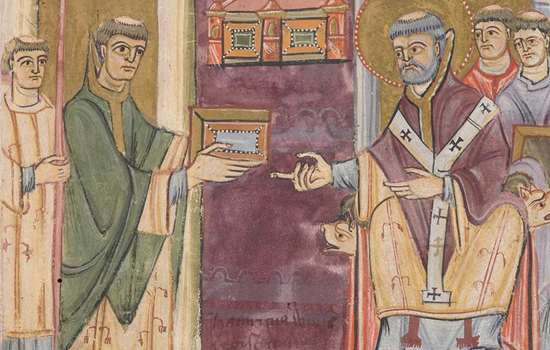

In 667, Pope Vitalian offered Hadrian the chance to become Archbishop of Canterbury. Hadrian, however, declined, suggesting as an alternative his friend Theodore, who was a monk in Rome. Theodore was originally from the Greek-speaking city of Tarsus in the Byzantine province of Cilicia (modern-day Turkey). Theodore, like Hadrian, was fluent in both Greek and Latin, and was, in the words of Bede, ‘learned in sacred and secular literature … of proved integrity’.

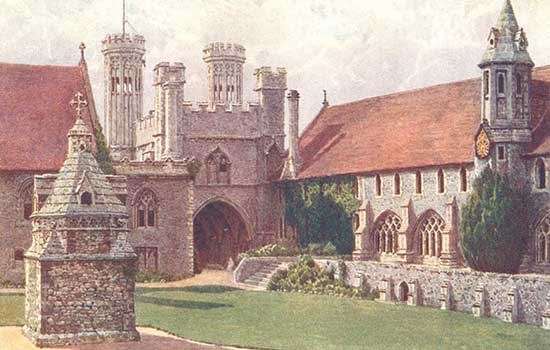

A condition of Theodore’s appointment, however, was that Hadrian should accompany him to Canterbury. On their arrival in Kent, Theodore immediately appointed Hadrian as abbot of the monastery of St Peter and St Paul. It was from here that St Augustine of Canterbury (died c.604) had spearheaded the conversion of Anglo-Saxon England some 70 years earlier. Hadrian obtained special papal privileges for his monastery and assisted Theodore in the administration of the Canterbury diocese.

Teacher and Scholar

Together Hadrian and Theodore also founded a school at Canterbury. This rapidly established an international reputation. Bede recounts how Hadrian and Theodore ‘attracted a large number of students, into whose minds they poured the waters of wholesome knowledge day by day.’ The curriculum included the Scriptures, poetry, astronomy and calculation of the Church calendar, introducing the teaching of Greek to Anglo-Saxon England. None of Hadrian’s complete works survive, but snippets of his writings from other early manuscripts show that he was a talented theologian and scholar and was familiar with the work of ancient Greek authors.

Among Hadrian’s students was Aldhelm (637–709), who later became Bishop of Sherborne and a saint. He lauded Hadrian as a ‘respected father and a reverend teacher’, also praising his ‘ineffability and pure urbanity’.

Aldhelm wrote Enigmata, a collection of 100 riddles inspired by the North African writer Symphosius, whose own book of riddles may have been brought to England by Hadrian. It is possible that Hadrian also brought with him a 4th-century copy of the writings of St Cyprian (c.200–58) who, like Hadrian and Symphosius, was of North African origin. This is one of the oldest known books to survive from Anglo-Saxon England

Influence and Death

In addition to the knowledge he passed on through literature and teaching, Hadrian also had a considerable impact on the Anglo-Saxon liturgy. With Theodore, he spread the use of music in church services, which had hitherto been confined to Kent. It is also due to Hadrian that the feasts of several central Italian saints were introduced to the calendar of the Anglo-Saxon Church.

Hadrian died in 710 and was buried at his Canterbury monastery. His remains – or relics – were rediscovered in 1091. Numerous miracles were attributed to Hadrian. His feast day is celebrated on 9 January, keeping alive the memory of the man who played such an important role in turning the Anglo-Saxon Church into an intellectual powerhouse of the early medieval world.

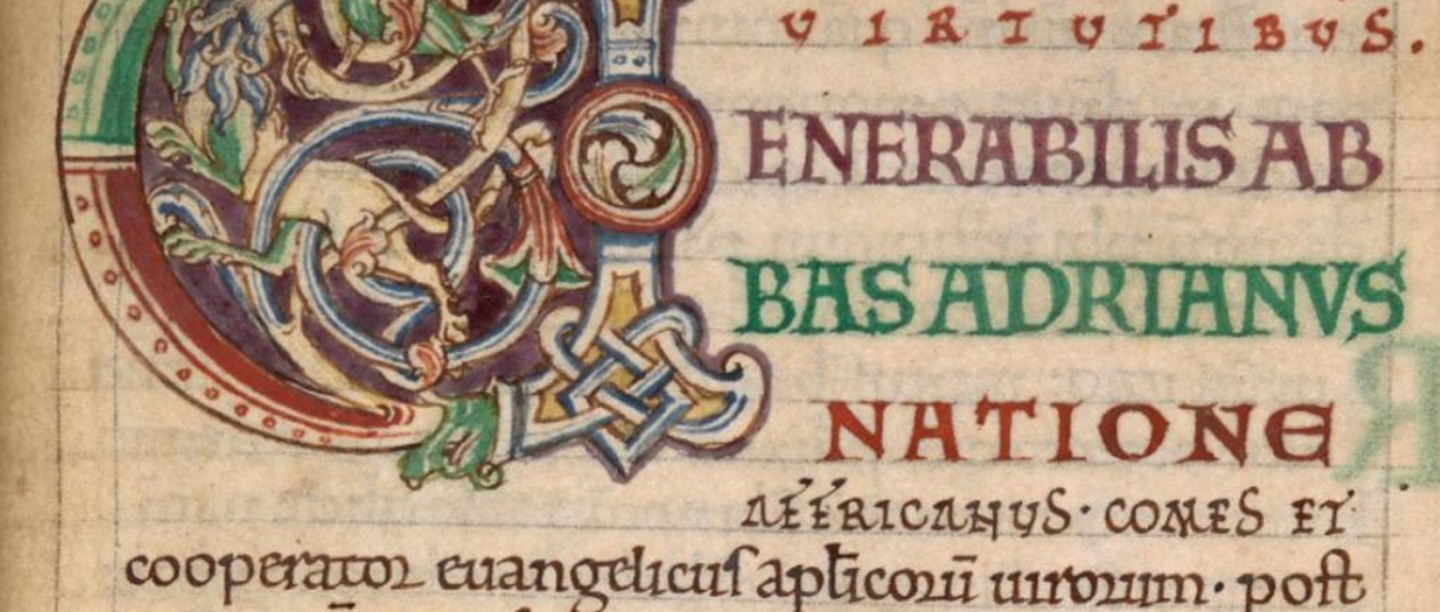

Top image: Detail from a 12th-century manuscript depicting the opening lines of Life of Hadrian. The text was originally written in the 11th century by Goscelin, a Flemish Benedictine monk.

© The British Library Board (Cotton MS Vespasian B XX fol 233r)

Read more

-

History of St Augustine's Abbey

Learn about the fascinating history of St Augustine’s Abbey, from its monastic golden age to its later existence as home to a royal palace, poorhouse and school.

-

Who was St Augustine?

In the late 6th century, a man was sent from Rome to England to bring Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons. But who was St Augustine, and how did his mission succeed?

-

Monasteries and abbeys

Learn more about England's medieval monasteries and abbeys and uncover the stories of those who lived and prayed in them.

-

A mini guide to medieval monks

Do you know the difference between the Benedictines, Cluniacs, Carthusians and Cistercians? This short animation will guide you through the different religious communities in medieval Britain.