The antiquaries

John Aubrey (1626–1697)

This Wiltshire-born antiquary made the first known accurate drawing of Stonehenge in 1666. He also identified ‘cavities in the ground’ which, 250 years later, were identified as pits and are now known as the Aubrey Holes. Aubrey’s observations at Stonehenge, Avebury and other stone circles around Britain led him to conclude they must have been built by the native Britons as they were often found in areas without association with the Danes, Romans or Saxons, as others had suggested. Deciding they must be temples, Aubrey was the first to link Stonehenge with pre-Roman religious leaders, the Druids.

William Stukeley (1687–1765)

As well as coining the term ‘trilithon’, the antiquary William Stukeley spent two and a half days in 1723 taking over 2,000 measurements of Stonehenge. His aim was to understand who built Stonehenge based on the units of measurement applied to its construction. In this way he ‘proved’ that Stonehenge could not be Roman because, using their unit of measurement, the distance between the stones produced fractions of numbers which he decided were ‘ridiculous and without design’. Like Aubrey before him, Stukeley attributed Stonehenge to the ancient Britons, more specifically the Druids. Stukeley’s observations also led to the recognition of the solstice alignment and the Avenue at Stonehenge, and surveys of the wider area led him to recognise the Cursus, which he decided must be some kind of Roman track for ‘games, feats, exercises and sports’.

William Cunnington (1754–1810)

Following his doctor’s orders to ‘ride out or die’, Wiltshire merchant William Cunnington took to regularly riding across Salisbury Plain. He was particularly interested in the ancient burial mounds he saw in the landscape and over a period of seven years, with the support of aristocrat Sir Richard ‘Colt’ Hoare, opened 465 barrows in Wiltshire, including Bush Barrow, where the pair discovered spectacular finds, now on display at Wiltshire Museum. Together Cunnington and Hoare devised a barrow classification system (e.g. bell, bowl, pond) which is still in use today.

Early Archaeologists

Professor William Gowland (1842–1922)

William Gowland was a metallurgist and archaeologist who was appointed to oversee excavations at Stonehenge in 1901, during the restoration of the severely leaning Stone 56. Gowland had worked for the Osaka Mint in Japan since 1872, spending his spare time excavating and surveying many prehistoric tombs, as well as collecting archaeological objects. Using techniques learnt in Japan, he carried out a meticulous investigation at Stonehenge which enabled him to state for the first time that it was a pre-metal, i.e. Neolithic, monument.

Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley (1851–1941)

In 1918 Stonehenge was transferred from private ownership into the care of the Office of Works. A survey revealed that several stones were unsafe and a programme of restoration was devised, with associated archaeological excavations to be overseen by William Hawley. After a military career, Hawley became an archaeologist, previously excavating Old Sarum hillfort. Work began at Stonehenge in 1919 during which time several stones were straightened. In 1920, Hawley turned his attention to the second part of his commission, which was to excavate the whole of Stonehenge ‘within and including the circular ditch and bank’. For seven seasons he excavated, often alone, during which time he excavated the Aubrey Holes, which seem to have held upright wooden posts and cremated human bones, as well as many other important features including the Y and Z holes and the ditch around the Heel Stone.

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942)

Known primarily for his work in Egypt, Flinders Petrie also spent time surveying monuments in Britain, after discovering that the British Museum did not hold recent plans of even the most famous stone circles and earthworks. With his father, who had taught him surveying, he began to survey Stonehenge in 1874, but the task was too difficult and was not completed until they returned in 1877. Flinders Petrie’s plan of Stonehenge was more accurate than any previously drawn, being measured to the nearest one-tenth of an inch. He also devised the numbering system for the stones which we still use today.

Maud Cunnington (1869–1951)

In 1925 and 1926, aerial photography revealed the outline of a circular ditched enclosure containing dark spots near the great henge of Durrington Walls. Distinguished Wiltshire archaeologist Maud Cunnington, together with her husband Ben and a small team of workmen, excavated the entire site over a year. It became clear that the dark spots were six concentric rings of post holes, enclosed by a small earthwork henge. Two burials were also found at the site – a male adult buried in the ditch, and a young child in the centre. This site, due to its proximity and similarities in design to Stonehenge, became known as Woodhenge. Maud Cunnington wrote the publication of the excavations and organised the presentation of the monument for visitors, marking the postholes with concrete posts.

20th-century archaeologists

Professor Richard Atkinson (1920–1994)

Along with fellow archaeologists Stuart Piggott and JFS ‘Marcus’ Stone, Richard Atkinson was asked by the Society of Antiquaries in 1950 to review the unpublished records of William Hawley in order to produce a definitive volume on Stonehenge. It was decided that further limited excavations were required to resolve some outstanding questions. At the time, Atkinson was a lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, but he later became the first professor of archaeology at Cardiff University. Atkinson remained involved in excavations during the major restoration project of 1958–64, during which key aspects such as the double bluestone arc were found. Although he wrote a popular book and made theories about the site accessible through television and radio appearances, he never fully published his research. In 1953, while taking photographs, Atkinson also identified a Bronze Age dagger and axe carvings on Stone 53.

Faith Vatcher (1927–1978)

With her husband, Major Lance Vatcher, Faith led excavations at a number of prehistoric sites in southern England, including several in the Stonehenge landscape, one of which was in the old Stonehenge car park. Here she identified three Mesolithic postholes dating from between 8500 and 7000 BC, revealing human activity some 4,000 years before the construction of the site we know today. The couple also excavated part of the Avenue, where it was crossed by the A303, as well as sites on King Barrow Ridge, at Winterbourne Stoke and Durrington Walls. Faith published many sites and wrote the official guidebook to the Avebury monuments.

Professor John Evans (1941–2005)

In 1978, John Evans was looking for snails, hoping to understand the prehistoric environment of Salisbury Plain. He was an environmental archaeologist at Cardiff University, with a specialist knowledge of land molluscs, which are useful indicators of past environmental and vegetation conditions. He excavated a trench across the Stonehenge ditch, and unexpectedly discovered the grave of a young man who came to be known as the Stonehenge Archer. Arrows embedded in this skeleton’s bones revealed the cause of death, but the reason for his demise is unknown to us today. John Evans excavated at many sites, building up the first detailed picture of the environmental history of southern England.

Current archaeologists

Professor Mike Parker Pearson

The Stonehenge Riverside Project directed by Mike Parker Pearson between 2005 and 2009 revealed at least seven Neolithic houses located at Durrington Walls. This was the most spectacular of a wealth of discoveries at various sites in the Stonehenge landscape, prompted by Parker Pearson’s theory that Durrington with its houses and timber monuments was an area for the living, whereas Stonehenge, built of stone, was a place for the dead. His most recent research has identified a stone circle in west Wales which may have been the original location for at least three of the bluestones now found at Stonehenge. Parker Pearson’s long career has included being an Inspector of Ancient Monuments, and teaching at the University of Sheffield and the Institute of Archaeology, University College London.

Mike Pitts

In 1979, when Mike Pitts was curator of the Alexander Keiller Museum in Avebury, he saw a trench being dug for the laying of a new telephone cable close to the Heel Stone. Believing that important archaeology was being destroyed, Pitts led a rescue excavation, identifying a large pit which, he suggests, may either have held a partner to the Heel Stone or was the site of its original position. Pitts later became editor of British Archaeology magazine and an author of books such as Hengeworld. He acted as consultant for a new visitor centre and continues to research Stonehenge, where his discoveries include the remains of a beheaded Anglo-Saxon man.

Professor Alex Bayliss

When the results of the 20th-century excavations at Stonehenge were finally published in 1995, a key aspect was the chronological development of the monument. Alex Bayliss, an expert on radiocarbon dating who at that time led the scientific dating team at English Heritage (now Historic England), used new techniques of statistical analysis to interpret all the radiocarbon dates available for the site. Bayliss contributed to the understanding of the phases of building at Stonehenge as well as shining a light on the pace of change in the Stonehenge landscape at the end of the third millennium BC.

Dr Ros Cleal

In the early 1990s, English Heritage commissioned Wessex Archaeology to pull together all of the archives from 20th-century excavations at Stonehenge, including those by William Hawley and led by Richard Atkinson, and properly publish them for the first time. Together with Rebecca Montague, Karen Walker and a range of other specialist archaeologists including Dr Mike Allen and Dr Julie Gardiner, Ros Cleal led this Herculean undertaking, which examined the evidence for the use of the monument from the Neolithic to the present day, resulted in a huge monograph, which is still an important reference volume. Cleal later became curator of the Alexander Keiller Museum in Avebury.

Find out more

-

History of Stonehenge

Read a full history of one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments, from its origins about 5,000 years ago to the 21st century.

-

100 years of care

In 1918, Cecil and Mary Chubb gifted Stonehenge to the nation. Our series of blog posts traces the conservation and care of Stonehenge over 100 years.

-

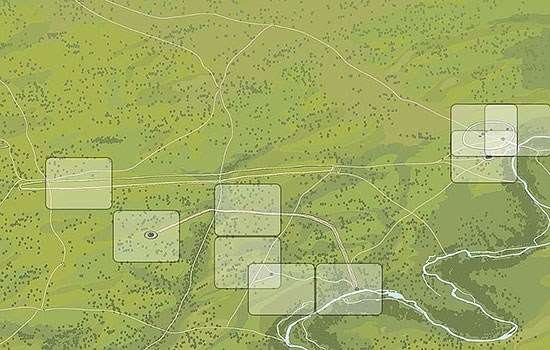

Explore the Stonehenge Landscape

Use these interactive images to discover what the landscape around Stonehenge has looked like from before the monument was built to the present day.

-

Research on Stonehenge

Our understanding of Stonehenge is constantly changing as excavations and modern scientific techniques yield more information. Read a summary of both past and recent research.