Ferguson’s Gang and Stonehenge

In the 1920s a campaign to save the landscape around Stonehenge captured the imagination of the public, enabling the land to be bought and donated to the National Trust.

The fundraising drive also inspired five young women to form Ferguson’s Gang, a mysterious and eccentric band who battled to save some of England’s threatened buildings and landscapes.

Polly Bagnall and Sally Beck, authors of a book about the Gang, explore the story of these women and their links with Stonehenge.

Heritage in peril

The late 1920s were a time of calamity for Britain’s heritage. Beautiful landscapes were being bulldozed for the construction of suburbs and roads – at this time there were no laws to restrict their development. Many historic buildings were being demolished or allowed to decay, and Stonehenge was endangered.

The nation rallied, and in the summer and autumn of 1927 there was a campaign to save the landscape surrounding the ancient stones. The monument itself was in good condition – since Cecil Chubb donated it to the nation in 1918, there had been a major programme by the Office of Works (a predecessor of English Heriitage) to restore and excavate the site. But although the stones themselves, and the triangle of land immediately around them, were now preserved, the same was not true for the surrounding chalk downland.

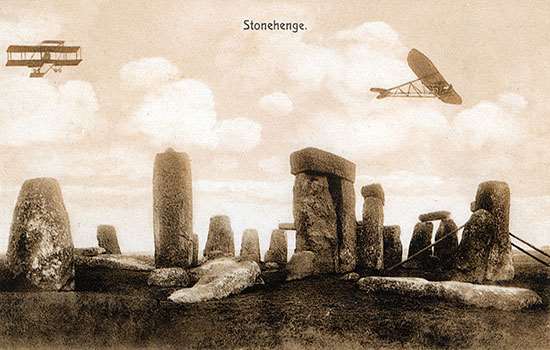

For a number of years, local archaeologists and residents had been alerting the government to one particular issue – the existence of a derelict aerodrome and its hangars very close to the monument. Although this First World War airfield had closed in 1921 and the buildings sold for demolition, the buildings still stood. The landowner, Isaac Crook, was using the land for a pig farm and had rented out some of the structures as dwellings.

Read more about the aerodromeThe Stonehenge Appeal

After months of meetings, writing letters to newspapers, and questions in parliament, the key people behind the campaign managed to secure the purchase of the land in July 1927. A public appeal was launched to raise money not only for this purchase, but for the fields all around Stonehenge, at an estimated cost of £35,000 – about £1.4 million in today’s money. Many feared that the land would be developed for bungalows or factories. The Stonehenge Protection Committee’s campaign leaflet warned:

The land of the plain around the stones is still in private property. So long as it remains in private hands, there is an obvious danger that the setting of Stonehenge may be ruined and the stones dwarfed by the erection of unsightly buildings … The Stonehenge ring, as every British child has learnt to picture it from his earliest years, will no longer exist.

The nation dug deep into its pockets, with even the king contributing 20 guineas. In March 1929 the appeal finally reached its target, with the land vested in the National Trust for its long-term preservation. The aerodrome buildings were gradually removed, the site cleared and the land eventually restored back to grassland. The nearby Stonehenge Café and custodians’ cottages were also demolished.

A mysterious band

In 1927 – the same year that this campaign was launched – five young women were inspired by the Stonehenge cause to form a philanthropic band that went by the name of Ferguson’s Gang. They vowed to save other historic buildings and landscapes in England from destruction and unsightly development.

These mysterious and eccentric women remained anonymous during their lifetimes, hiding behind pseudonyms such as Bill Stickers, Red Biddy and The Bludy Beershop. Determined and resourceful, despite only being in their early 20s, they raised a fortune to preserve properties in Surrey, the Isle of Wight and Oxfordshire, as well as several beauty spots in Cornwall.

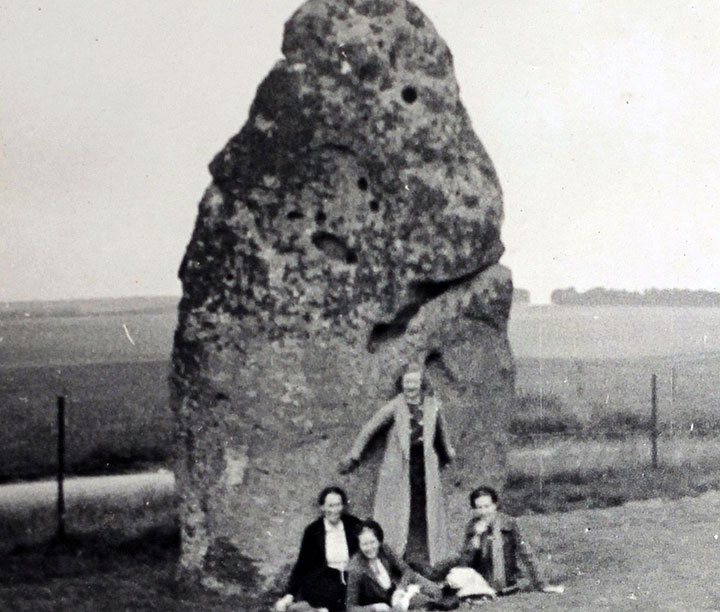

Their inspiration was always the Stonehenge landscape, and they adopted the ancient monument as their emblem. Their motto was ‘England is Stonehenge not Whitehall’. So strong was their attachment to the prehistoric stone circle that they visited together for the first time in 1932, and again for their tenth anniversary in 1937. They enjoyed a pilgrimage to the site, celebrating with an exotic picnic washed down with a good bottle of vintage wine.

The gang to the rescue

The Gang made donations to many National Trust appeals, but by 1932 they had raised enough money to buy one outright. Shalford Mill near Guildford, Surrey, was part of the Godwin-Austin family estate. It was falling down, despite an impressive history – it was mentioned in the Domesday Book.

By the time the Gang began raising funds to save it, the mill had been vandalised, tiles were hanging off the roof and there was scarcely a window that had not been shattered. Its sensitive repair was successfully overseen by a conservation architect, John Macgregor, who became an honorary member of the Gang. He adopted The Artichoke as his pseudonym and went on to oversee two other conservation projects for the women.

In 1934, the Gang rescued the Old Town Hall in Newtown, Isle of Wight. In 1935 and 1936 they bought Mayon and Trevescan cliffs in Sennen, Cornwall. Priory Cottages in Steventon, Oxfordshire, a former priory, came next in 1938, before the Gang’s final purchase, of Frenchman’s Creek in Cornwall in 1946.

Making the headlines

Along the way, the Gang acquired a headline-grabbing reputation for delivering money to the National Trust for these purchases in delightfully strange ways – Victorian coins inside a fake pineapple, a £100 note stuffed inside a cigar, £500 with a bottle of homemade sloe gin. Their stunts attracted plently of press coverage, securing valuable publicity for the National Trust. This in turn swelled the Trust’s coffers and the gang became their most successful benefactors.

The members of Ferguson’s Gang clearly had great fun during their meetings and campaigns, often staying up all night at midsummer to re-enact solstice rituals, again inspired by their visits to Stonehenge. But their ideas about preservation and conservation were serious and many would be later enshrined in planning and conservation law. These brave and strong-headed women were decades ahead of their time.

Further reading

Polly Bagnall and Sally Beck, Ferguson’s Gang: The Remarkable Story of the National Trust Gangsters (National Trust, 2015)

Find out more

-

100 years of care

In 1918, Cecil and Mary Chubb gifted Stonehenge to the nation. Our series of blog posts traces the conservation and care of Stonehenge over 100 years.

-

The First World War Stonehenge aerodrome

As they travel from the visitor centre to the stones, few of today’s visitors to Stonehenge realise they are crossing the site of a First World War airfield.

-

Explore the Stonehenge Landscape

Use these interactive images to discover what the landscape around Stonehenge has looked like from before the monument was built to the present day.

-

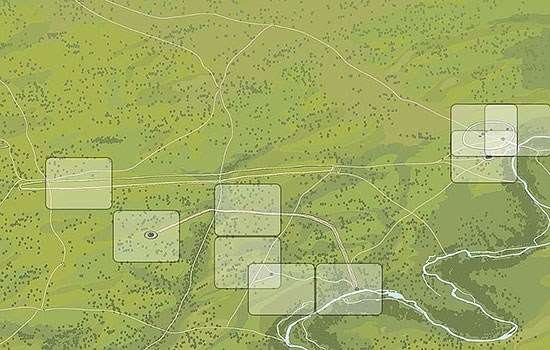

The Stonehenge World Heritage Site Landscape

Explore this interactive map created by Historic England to find the latest in-depth research into the Stonehenge World Heritage Site landscape.