Restoration begins

On 26 October 1918 Cecil Chubb, the owner of Stonehenge, formally handed it over to the Office of Works. An assessment of its condition soon followed and plans were made to straighten a number of the leaning sarsens and securing them in a concrete foundation, as well as re-erect the stones that had fallen in 1797 and 1900.

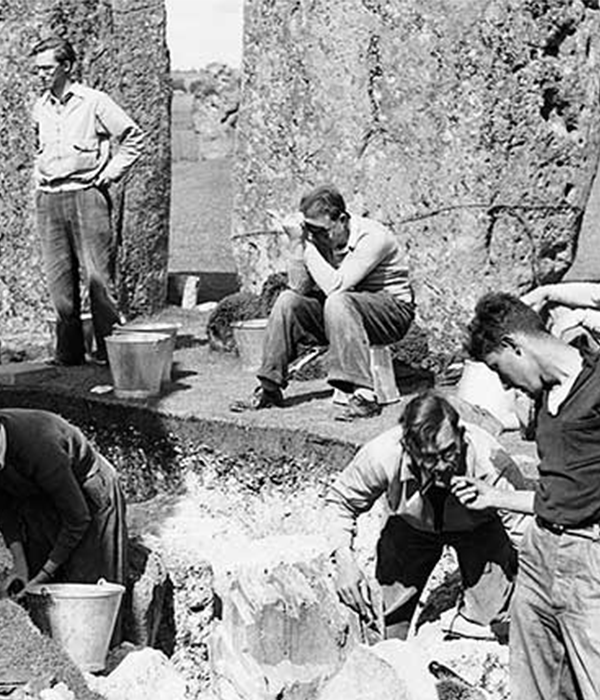

Work began in 1919, focusing on the stones that the Office of Works deemed most in need of restoration. The Society of Antiquaries carried out the excavations, which were directed on their behalf by Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley.

Stones 6 and 7, both of which were leaning precariously, were straightened and their lintel was replaced. Stones 29, 30, 1 and 2 of the outer circle were straightened and set in concrete. Plans to raise the stone that fell in 1900 and the trilithon that collapsed in 1797 were not fulfilled at the time.

1950s restoration

Not surprisingly, little happened at Stonehenge for an extended period during and after the Second World War. But in 1950 the Society of Antiquaries asked a team of three experienced archaeologists – Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott and JFS Stone – to write up a ‘full and definitive’ volume on the archaeology of Stonehenge.

Atkinson, Piggott and Stone wrote a report in which they recommended the restoration of the entire trilithon – two upright stones capped by a lintel – that had fallen in 1797. It also proposed that two other stones in the outer sarsen circle that had fallen in 1900 should also be restored, as well as any other stones that were in danger of collapse. The Society backed them and the Ministry of Works accepted the proposals for restoration on the basis that they ‘would enhance the value of the monument for the student and make it more intelligent to the ordinary visitor’.

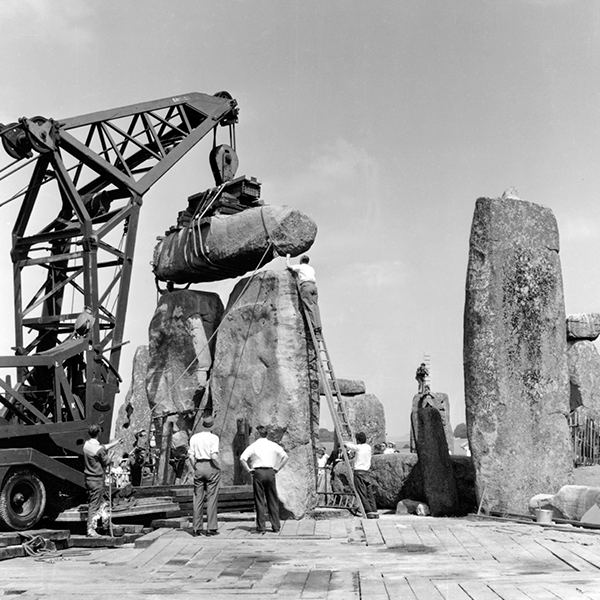

This major engineering project and associated excavations began in 1958 and continued into 1959. Atkinson, Piggott and Stone together oversaw the archaeological work. The trilithon was re-erected from the position where it had lain for 161 years. An upright and a lintel forming part of the outer circle were also put back into position. One of the large sarsens of the inner horseshoe was set in concrete and a large hollow at its base infilled. Further sarsen stones were set in concrete to prevent future movement. Finally, six fallen bluestones were lifted and straightened.

Last major works

These two seasons of restoration were supposed to complete the project. But on the morning of 10 March 1963, calamity struck: one of the stones in the outer circle fell during high winds. A long period of frost in the early spring, followed by a rapid thaw and heavy rain, was said to be the cause. However, this stone had also been given a hefty knock during the works to re-erect the adjacent stone.

Inspectors rapidly surveyed the whole site, amid fears that further stones would fall onto unsuspecting visitors. Monthly readings were taken to monitor any movement. This showed that three stones in the outer circle, as well as the so-called Great Trilithon, were indeed moving and needed to be secured. So in 1964, in the final phase of restoration at Stonehenge, all these stones were secured in concrete and the fallen sarsen in the outer circle was re-erected.

Conservation in action

In the 1960s, conservators used cement mortar to fill in cracks and fractures on the horizontal stones that sit on top of the huge upright stones.

Cement mortar isn’t breathable, and as it degrades, it leaves the stones vulnerable to damage from trapped moisture. In September 2021, conservators replaced this with lime mortar to keep water out as well as to allow any water that does get in to escape.

Lime mortar is a traditional breathable material, unlike modern cements. It allows water to escape rather than sit in cracks where it can freeze and expand, causing erosion.

While carrying out the work, care was taken to protect the many different types of lichens that grow on the stones. They are an important part of the ecosystem, and a vital part of the character of the stones themselves.

Click on the images below to find out more about the people who have undertaken conservation work at Stonehenge.