Before the Romans

When the Roman army moved into the central Shropshire plain, the landscape they found had been settled and cultivated for more than 1,500 years. It was occupied by a people known to the Romans as the Cornovii. We don’t know when they came into being, but excavated sites show that most lived in farmsteads dotted across the landscape. They may also have occupied the many hillforts in Shropshire such as the Wrekin, which lies close to the later city of Wroxeter.

The Cornovii did not use coins, and their pottery use seems to have been mainly limited to large containers containing salt traded from the salt springs in Cheshire, which also appear to have been part of their territory. Instead of pottery, they probably used vessels made from leather and wood, both abundant resources in their landscape.

The territory of the Cornovii was landlocked, but they would have used the Severn to reach areas and people to the south. There is evidence for sophisticated metalwork – fittings from metal vessels, chariots and elaborate brooches – perhaps used by elite groups in their society. But there is no sign of warfare or conflict. Their wealth seems to have lain in livestock management, perhaps especially cattle (which may have been seen as a form of wealth) but also sheep, in areas where conditions for cattle were less favourable.[1]

Roman occupation

The first evidence we have for Roman contact with the Cornovii is the arrival of the Roman army in the late 40s AD, about four years after the Roman invasion of Britain. They built temporary campaign camps on both banks of the Severn, at Cound and Leighton, to control crossing points, and made a second approach along high ground to the north of the Wrekin, which later became Watling Street.[2] They do not seem to have met much resistance – although it is possible that the Wrekin hillfort was attacked at some point – and the local people may have welcomed the Romans.

A fort for 500 cavalrymen was established around AD 47 south of Wroxeter village, which controlled the ford there. The tombstone of the cavalryman Tirintius suggests that it was occupied by a cohort of Thracians, from modern Bulgaria or Greece.[3]

Around a decade later, with the surrounding countryside under Roman control, a fortress replaced the fort a kilometre to the north. This formed the nucleus of the later city. The construction of the fortress meant taking in a large area of the native people’s land – not just the area of the fortress but enough land around it to support the fortress and the people within it.

Undoubtedly, this first phase of occupation would have shocked and disorientated the local people. As well as losing property and certainly suffering some violence from the soldiers, they would have had to adjust to the Roman way of doing things, such as using money and speaking a new language.[4]

Learn more about daily life in Roman BritainWroxeter’s fortress

The 14th legion built the fortress on high, free-draining ground above the river Severn. The Bell Brook, a stream running north of the fortress, supplied ample water, and the site commanded both the ford across the Severn and the surrounding land.

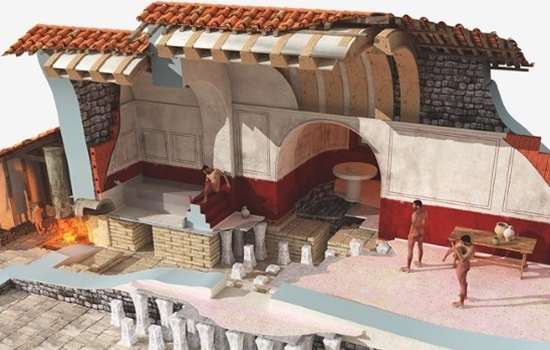

The fortress was designed to provide everything the legion required: living space for its 5,000 troops and 500 cavalrymen; workshops; stores; a hospital; the headquarters building; a bath house; accommodation for the men in barracks; houses for the officers; and a mansion for the commander.

Only the officers and commander were accompanied by their families. Soldiers were not allowed to marry while in the army, although many formed relationships with women who lived locally or who had followed the legion from their former base in Mainz, Germany.[5] Formal recognition of these women, and any resulting children, came when the soldiers retired and acquired Roman citizenship after 25 years’ service.

The fortress was like a town in its own right. All the necessary food was acquired locally but supplemented by produce that could not be found in Britain, such as olive oil, wine, dates and figs, and goods such as glass vessels and fine pottery. Soldiers who were trained in crafts such as woodworking, leathermaking, iron-smithing, metalworking and potting catered for the everyday needs of the army, while other soldiers were architects, plasterers and engineers who provided the expertise for building.

The creation of the bustling fortress attracted people from the local area and further afield to settle outside in a settlement called the canabae (booths). These people were under the formal control of the army and many who lived there were the families of the soldiers, as well as traders and merchants.[6]

Transition to civilian life

The fortress was used as a campaign base throughout the 50s and 60s AD, with the 14th legion being replaced by the 20th in around AD 68, until Wales was finally conquered in AD 78.

In that year, the governor Agricola, a former commandant of the 20th legion, probably led out his campaign force, which had been assembled in camps north of the fortress, for the conquest of north Wales and then northern Britain. As the legion moved further and further north, Wroxeter fortress became more of a depot than an active base. And when the legion started to build a new fortress at Inchtuthil in Scotland around AD 85, it was clear that Wroxeter was redundant.[7]

The army levelled the defences of the fortress, but its street grid (and perhaps a number of its buildings) were retained as the nucleus of the new city.[8] It is likely that a substantial number of veteran soldiers and their families became part of the early community of the city. Tombstones of three soldiers are known, all of whom originated in northern Italy.[9]

The early city

While the buildings of the fortress contributed to the early city’s townscape, the city founded by the new civic authority – probably a mixture of local elite families and veteran soldiers – was four times larger than the 16-hectare fortress. The 78-hectare city was laid out by using the existing street plan of the fortress, the grid-iron pattern indicating that it was laid out by trained surveyors who must have been veteran soldiers.

A total of 48 city blocks were created, with the main street coming into the city from the north-east and then turning north–south to run down to the ford. A major east–west street formed a crossroads in the centre of the city, close to the current crossroads near the museum car park and farm buildings.[10]

It is unlikely that this ambitious street grid was fully occupied, certainly at this early period, but it led to the fields and land beyond the city via trackways still visible in aerial photographs.[11] Even at this early date, the ambition of the city founders tells us that Viroconium was the designated capital of the Cornovii – hence Viroconium Cornoviorum.

Only one early civic building can be identified – a post-inn or mansio – like the one known at Wall to the east. However, it is likely that some of the temples we can see may have been founded at this date too.

The mature city

While much of the city is unexcavated, research through geophysics and aerial photography has contributed considerably to our understanding of the city.

It demonstrates that there are around 240 houses, most of them likely to be stone-founded, and with timber and clay superstructures. These are mostly in the centre and west of the city, which tells us that they are likely to be houses of the more well-to-do people, as well as some commercial properties.

The less well off probably lived in the outlying areas, or in back plots in the centre such as in the east and north of the city – we can see activity and the vague outlines of houses there, but little detail.[12] These houses will have been made of timber and clay. The combination of timber and open hearths led to at least two major fires in the city’s history, both of which are likely to have been accidental. Fire was a common hazard in cities.

The core of the city, its civic centre, was completed between AD 130 and 150. This comprised a civic bath house that also included a market hall and shops. On the other side of the road was the city’s forum – its official marketplace, county hall and judicial centre. To the north of the forum, under the modern farm buildings, was another large civic building, almost certainly Wroxeter’s main civic temple.[13]

As in pre-Roman times, the wealth of the city probably lay in livestock. A large open area at the highest point of the city may well have been the site of its livestock market, which supplied materials for many trades in the city, such as bone working, leatherwork and textile production.

At the end of the 2nd century or the beginning of the 3rd, a city wall was added. This was not built in stone but in timber and turf, like a Roman fort or native hillfort.[14] There is no evidence for an attack on the city that would have prompted the addition of defences and it is more likely that this was an expression of the civic status of Viroconium.

The later city

While it is difficult from the little that has been excavated to completely understand what happened in Wroxeter in the 3rd and 4th centuries, it is clear that there was change and eventual decline.

In this, Wroxeter mirrors what was happening not just in Britain but across the Empire at this time. Internal conflict and external pressures combined to make the Empire more unstable, while the failure of the army to conquer new territory meant that the state was paying out more than it was gathering in taxes. The resulting inflation undermined the way that Roman towns were governed.

At Wroxeter this can be seen, for instance, in the increasingly dilapidated appearance of the civic bath buildings and even the partial abandonment of the forum early in the 4th century. Massive civic buildings are expensive and difficult to maintain, so it was easier to take them down than to repair them once they became dangerous to use, as was the case by the end of the 4th century. Economic decline and social change caused the city to become a less desirable place to live, and by the mid 5th century Wroxeter’s city centre had been abandoned.

After the Romans

While much of Wroxeter gradually decayed and returned to the farmland it had once been, people did not completely abandon the city. A small community stayed close to the ford, where the modern village is, clustered in time around the Church of St Andrew. This was built opposite the road leading to the ford and aligned on the Roman street grid.

While the earliest fabric of the church is perhaps 10th or 11th century in date, an 8th-century cross survives to show that in the Anglo-Saxon period Wroxeter was still considered important. Pieces of the cross, including animal carvings, were built into the south wall of the church in the mid 18th century. The church also incorporates Roman stonework robbed from the site of the Roman city.

The church may well be the successor to an earlier British Christian community, the last remnants of Wroxeter’s Roman inhabitants.[15]

About the author

Dr Roger H White is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham's Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology. He has been working on Wroxeter for nearly 50 years as an excavator and researcher.

Why did the Romans leave Britain?

Curious to find out more about why the Romans left Britain? In this article Curator of Collections Cameron Moffett explores how and why the 400-year Roman occupation came to an end and what sort of Britain was left behind.

Find out MoreFind out more

-

Significance of Wroxeter Roman City

Wroxeter is probably the best-preserved Roman city in Britain, as well as one of the largest, although only a fraction of it can be seen today.

-

Research on Wroxeter Roman City

Wroxeter’s importance as a major Roman city in Britain underlines the importance of continuing to research its past.

-

EXPLORE ROMAN BRITAIN

Browse our articles on the Romans to discover the impact and legacy of the Roman era on Britain’s landscape, buildings, life and culture.

-

Roman Bathing

Read about Roman bathing and discover what Roman bath houses reveal about the culture and people of the time.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook provides a full tour of Wroxeter Roman City and explains the complex history of its rise and decline.

-

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan of the baths complex at Wroxeter to see how the buildings developed over time.