Women’s ornaments

There’s plenty of evidence for women at Wroxeter in its later, civilian heyday but we also know that they were present from the outset, when the site was a legionary fortress. This tiny silver hair ornament confirms that an elite woman arrived with the army.

Only 13mm long, this is part of a complex hair accessory. At the top is a mano fica (fig hand) – a potent gesture very popular with Romans, in which the thumb is inserted between the middle fingers of a clenched fist, making a shape resembling female and male genitals in the act of sex. The other end of the ornament depicts a phallus. The ornament’s off-centre perforation means that it would have hung with the fist at the top.

These two motifs were used in antiquity to protect against the evil eye. Although images of the mano fica and the phallus are usually seen on men’s accessories, this was not a rule – as demonstrated in the use of silver here. Silver, with its references to the moon, was a metal worn by women.

Women’s Cosmetics

Women’s cosmetics were introduced to Britain from the Roman empire at the end of the Iron Age. This was followed by a rapid development of new equipment to grind and apply make-up: these were small mortar-and-pestle sets made of bronze (copper alloy), with suspension loops enabling them to be hung together from a cord. These cosmetic sets first appeared in south-east Britain and the trend spread to Wroxeter. The base of a cosmetic, for example charcoal used to define eyes and brows, was put in the mortar, ground and applied using a pestle.

Small mirrors became quite common possessions in the first two centuries of Roman Britain. From the 3rd century AD, evidence for a new, more affordable way to prepare cosmetics is seen at Wroxeter through small palettes of stone, used together with naturally rounded stones for pestles.

Women and textiles

In Rome, women produced their family’s clothes, although the wealthy could buy ready-made items. In Britain, with its own long tradition of textile production, making clothing in the home would have been familiar. Combed wool fibres were spun into a thread using a spindle weighted with a whorl at the bottom to make it spin effectively. The thread would be woven on a loom into long pieces of cloth. The shuttle was used to convey the weft thread back and forth between two sets of upright warp threads; the pin beater is to knock the stitches down to tighten the weave.

Garments of the period were usually made of one piece of fabric that could be minimally shaped on the loom. This would then be sewn up the side to make a tunic or a tube dress, which could be pinned at the shoulders with brooches. The four-holed weaving tablet was used to produce woven strips that could be used for belts or as trims.

Roman gods

As a newly founded town of the later 1st century AD, Wroxeter developed along Roman lines and had appropriately Roman gods. The gods most often depicted in sculpture and small works of art here are two of the most popular Roman deities: Hercules and Venus. It’s unsurprising that a wealthy city population with a livestock-based economy favoured gods well-known as icons (respectively) of manliness and the female principal, whose myths spoke of fertility and bountiful harvests.

Other deities at Wroxeter also promised abundance: Ceres, the goddess of grain and fruitfulness, and Diana, goddess of the moon and associated with childbirth. A shrine was also idedicated to Bacchus, the ever-popular god of wine and mayhem.

VIEW IN 3DMagic

Women’s magic was present in all pre-modern societies and mainly related to childbirth, fertility and relationships. It covered a wide range of beliefs and activities that could include potions, curses and spells with malicious intent, to more benevolent ones for love or healing. It’s likely that these sub-genres of women’s magic were practised by different people.

Much was written about witches and witchcraft by the authors of antiquity but archaeological evidence is rare because most of what is involved in magical practice has left no trace.

This protective amulet is made from jet, a lustrous black material used mainly for jewellery (especially women’s) and providing a useful physical expression of what people believed in the Roman period. It has physical properties that would have made it appear to be a magic material in antiquity: rubbing jet generates a mild electrical charge. Despite looking like stone, it also burns and floats due to actually being petrified wood.

Superstition

A superstition probably universal during this period was the belief in the evil eye, with most illnesses and disasters attributed to its curse. The image of a phallus was a commonly used defence against the evil eye and there are many objects at Wroxeter on which it appears. People believed that the phallus would act as a decoy: the surprising image distracting the evil eye away from its original target – one’s own eye.

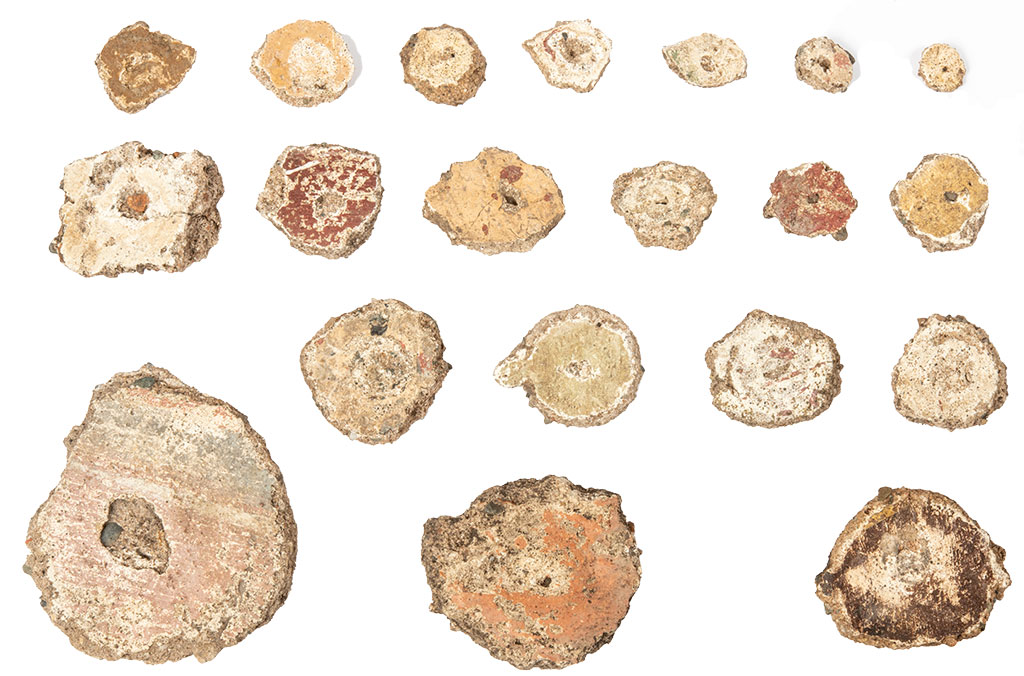

Another decoy used to trick the evil eye was an eye-shaped object. Wroxeter is well known for its large assemblage of pieces of wall plaster, chosen for their resemblance to an eye. These found objects pictured here may have been another form of protection against the ever-present evil eye.

Drinking objects

Alcohol was socially and nutritionally important in antiquity. Finds from Wroxeter provide evidence for the serving and consumption of alcohol, as well as production and storage, over 400 years.

In the pre–Roman Iron Age drinking alcohol in a group, especially as part of a feast, reinforced social bonds. Alcohol (mead or ale) was usually served in buckets from which individual cups were filled using a ladle. These buckets were often decorated, particularly along the rim.

The earliest object found at Wroxeter is a figurine of Castor or Pollux. It was originally a mount on the rim of a wine bucket in Italy (1st century BC) before it broke off and was adapted into a pendant.

Home brewing

Locally made drinking vessels were used for beer and mead. Drinking cups in a tankard shape had been created from hardened leather in Iron Age Britain. After the Romans introduced mass production of ceramics, the kilns that were established around the new town of Wroxeter brought in a ceramic version of the traditional tankard. In the later Roman period, when imports of wine from the Mediterranean were less available due to political disruption on the continent, evidence for mead-making appears. From the 3rd century, bungs and stoppers (made of stone) appeared in large numbers. Coated with beeswax, bungs were used to stop up flagons in order to transport them or to use the flagon to ‘lay down’ mead. Mead improves with ageing and was the only alcoholic drink made in ancient Britain with a high enough sugar and alcohol content that it could be kept.

VIEW IN 3DWine and its accessories

The period during which the Roman army progressed through Britain in the 1st century AD corresponded with the mastering of glass-blowing technology in the Mediterranean regions. Across the empire, glass vessels became affordable and available as they were easy to transport. The trade in wine from the Mediterranean expanded into Britain and items needed for drinking and serving wine in the Roman way became particularly desirable and were traded widely. While alcohol had always been important, exotic imported wine had additional kudos and was stronger than local brews.

Two 2nd-century glass wine beakers imported from the major glass production centre in Roman Cologne have been reconstructed and are on display at Wroxeter’s site museum. These would have been part of a wide range of glass vessels seen on the dining tables of the elite, including serving dishes, cups, bowls and jugs for serving wine.

Find out more

-

History of Wroxeter Roman City

Founded in the mid 1st century AD, Wroxeter was one of the largest cities in Roman Britain and is exceptionally well preserved.

-

Research on Wroxeter Roman City

Wroxeter’s importance as a major Roman city in Britain underlines the importance of continuing to research its past.

-

Significance of Wroxeter Roman City

Wroxeter is probably the best-preserved Roman city in Britain, as well as one of the largest, although only a fraction of it can be seen today.

-

Collection at Wroxeter Roman City

Tens of thousands of objects provide evidence about the lives and beliefs of Wroxeter’s civilian inhabitants from the 2nd to 4th centuries AD.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook provides a full tour of Wroxeter Roman City and explains the complex history of its rise and decline.

-

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan of the baths complex at Wroxeter to see how the buildings developed over time.