What is a meadow?

A meadow is an area of grassland which is left to grow long through the spring and summer months. In late summer, the grass is cut for hay to feed animals in the winter, and the area is then grazed until the ground becomes too wet. This makes it different from pasture which is grazed all year round.

Meadows can look very different, depending on what is growing in them, but the key feature is that the vegetation is left during the growing and flowering season, and then cut. This system provides an ideal habitat for many wildflowers as it gives them time to flower and set seed before the grass is removed.

Early Grassland Landscapes

Many of English Heritage’s oldest sites are situated in open grassland. The semi-natural grasslands around Stonehenge, Wiltshire, and Grimes Graves (a prehistoric flint mine in Norfolk) appear much as they would have done during the Neolithic period. Pollen analysis at our sites can determine what sort of vegetation might have been present hundreds or even thousands of years ago.

Early farmers often used tree branches as fodder for their animals in winter, when grass was scarcer. Haymaking from grass probably developed alongside metal blades in the Iron Age and the Bronze Age as it would have been easier to cut the grass than with early flint tools. Keeping an area as long grassland now helps us to protect archaeology at our sites which might otherwise be disturbed by ploughing or footfall.

Meadow Evidence 1000 years ago

Roman texts and surviving features in Roman sculptures show haymaking was part of Roman agriculture. Long Roman scythes have been found in Britain, which may have been used for hay or cereal crops.

Meadows were widespread in the Anglo-Saxon farming landscape. Charters give us descriptions of land, distinguishing between pasture and meadow as different forms of grass management.

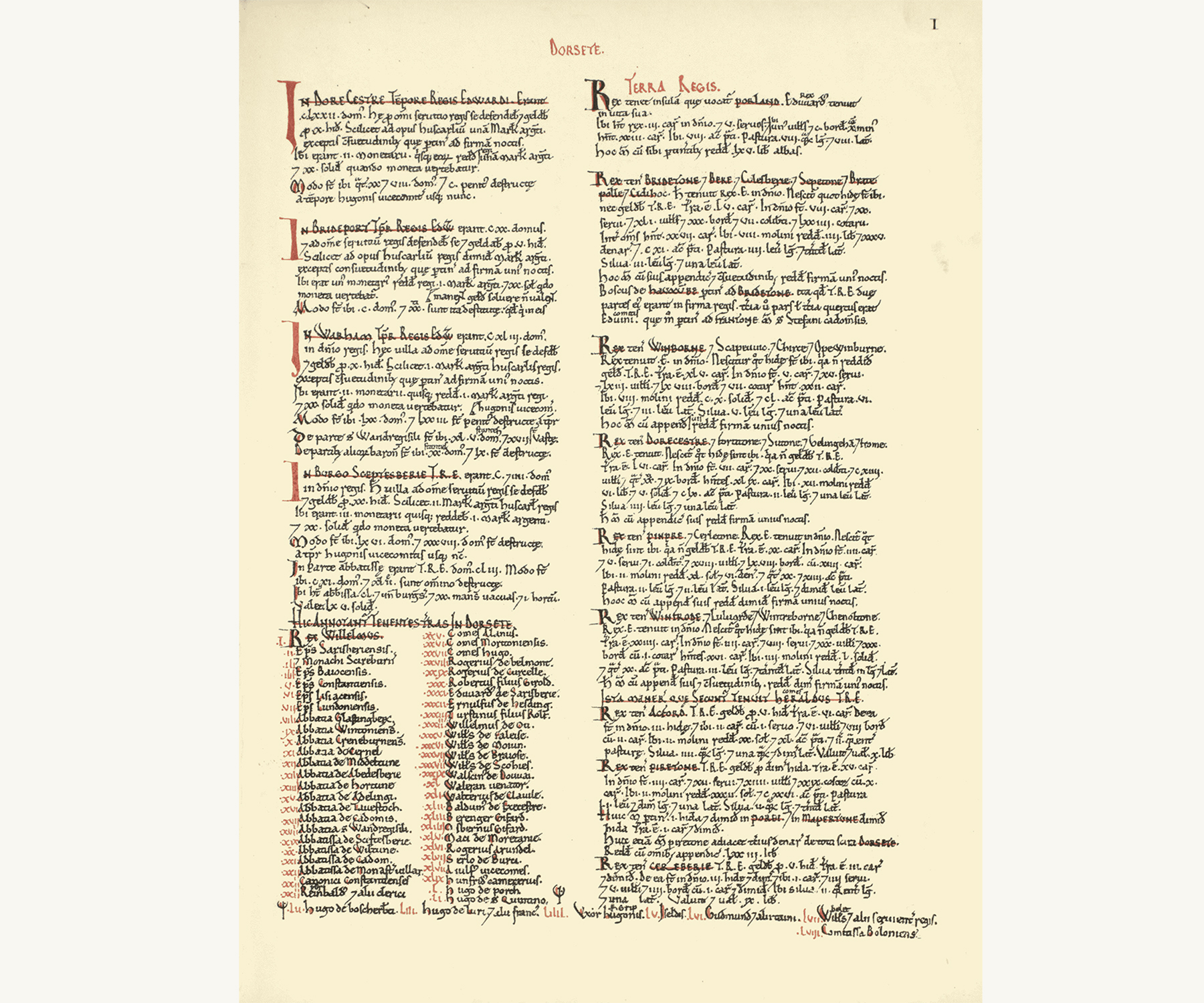

After the Norman Conquest (1066), meadows were a distinct and valuable category of land in the Domesday survey of 1086, although the records were inconsistent across the country. The size of a meadow was recorded in either acres or ‘ploughs’ – a measure calculated by the amount of land which could be ploughed with a team of eight oxen. Near Maiden Castle in Dorset, the Domesday entry for Winterborne recorded 80 acres of meadow, showing how prevalent this type of landscape was in the area over 900 years ago.

Medieval Meadows

Meadows were a central part of medieval agriculture and a valuable resource. The wool trade which made parts of the country very wealthy, such as East Anglia, relied on hay crops to keep livestock through the winter months. Expansion of livestock farming increased demand for hay and therefore increased the value of meadows further.

Meadows were often given in land grants as valuable gifts to abbeys and monasteries, such as to Leiston Abbey in Suffolk which has records of meadow land grants from the 12th century to the 16th century.

Meadows could also be found in castle landscapes, such as surrounding the Mere at Kenilworth in Warwickshire, and at Framlingham Castle in Suffolk, benefitting from any seasonal flooding.

Water Meadows

Water meadows were first developed by medieval farmers, and the practice continued until the late Victorian period. Water meadows are a form of irrigation which encouraged greater hay crops and richer grazing land once the hay was cut. Channels were cut in grassland next to rivers or streams so that water could be diverted to flow across the grass depositing rich silt onto the meadow. The channels were designed so that they could be blocked or opened to control the flow. These complex systems took many different forms, often with regional variation.

Water meadows were an important part of agriculture until the recession of the late 19th century. Where they have not been ploughed up, water meadows leave strong earthwork remains in the landscape. They can be seen along the River Nare at Castle Acre in Norfolk, where they were used until the First World War.

In 1849, William Morris wrote a letter to his sister, and described wading through water meadows on his way to Silbury Hill in Wiltshire:

… I will tell you what a delectable affair a water meadow is to go through; in the first place you must fancy a field cut through with an infinity of small streams say about four feet wide … the grass being very long you cannot see the water til you are in the water and floundering in it .... Luckily the water had not been bog when we went through it else we should have been up to our middles in mud...

18th-century pastoral scenes

Haymaking and teams of scythe men were a part of the idealised pastoral landscape in the 18th century. Inspired by classical poetry and paintings of Arcadian landscapes, wealthy 18th-century landowners travelling around England often commented on the ‘rich’ views in front of them and enjoyed watching haymaking. They saw the fertility and productivity of the countryside, idealising the lives of the working rural population, though often overlooking any hardship. At Wrest Park, Bedfordshire, Jemima Yorke frequently watched the ‘haymakers’:

The fields are busily full of Haymakers; the Verdure they leave behind them dresses the Country in new Beauty, & the Fragrance of the Fields the Hedges & Gardens vye now with each Other.

At Kenwood, London, the land beneath the model dairy (built c.1795) known as West Meadow has probably been managed as meadow since at least this date, providing hay and grazing for cattle in the 18th century, and grazing for sheep until the 1950s.

19th-century agriculture

Meadows continued to be a valuable agricultural resource in the 19th century, although different forms of livestock feed such as root crops and oil cake were becoming more widespread. The 1836 Tithe Commutation Act allowed the payment of tithes – one tenth of annual produce to be paid to the church, a practice predating the Normans – to be paid in cash. This required a national survey to establish land ownership, on a scale unlike any since the Domesday Book.

The records from the 1830s and 1840s often noted where land was meadow. They show us Houghton House, Bedfordshire, was surrounded by meadow in 1843, and that there was ‘Meadow in [the] castle’ at Berkhamsted Castle, Hertfordshire, in 1839.

There was also a meadow inside Tilbury Fort, Essex, in the 19th century which supplied ‘a crop of hay in the summer’ for the horses at the barracks. An article from 1854 described:

The agreeable vision of a haymaking party – “The mower whets his scythe;” said mower being an artilleryman in his uniform, all but his coat: and the first sound we hear is the crisp, cutting hiss of his rural blade as it shears sharply through the heavy swathe of grass…

Threats to Meadows

Since the end of the 19th century, meadows have been under threat. Alternative winter feeds meant hay crops were not as valuable and there was increased demand for arable crops from the growing urban population. This intensified during the First World War and towards the end of the 1930s when war loomed again. ‘Plough-up’ campaigns enforced farmers to plough up proportions of permanent grassland for crops like wheat or potatoes to keep Britain fed during the war. By the end of war, 40% of previous grassland had been ploughed.

The momentum continued after 1945, until an estimated 97% of the semi-natural grassland which had been present in England and Wales had been lost by 1987, either due to ploughing for crops or urban development. Since the 1960s, efforts to conserve and protect meadows have been growing and today the value of meadows for pollinators and biodiversity is widely recognised.

Read about how we conserve our meadows100 Meadows across 100 historic sites

To celebrate the coronation of His Majesty King Charles III in 2023, we are creating and enhancing 100 meadows at our castles and abbeys, prehistoric stone circles and palaces.

Over the next decade English Heritage – working with Plantlife – will create a natural legacy at 100 of our historic sites, establishing flower-rich grasslands right across England. From Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain to the Jewel Tower in the heart of Westminster, we will be reviving natural meadows which have been lost, and revitalising those that already exist.

Read moreExplore More

-

Conserving England's Meadows

-

Caring for our Gardens

-

Visit our Gardens