NORMAN RULE

William and his knights, and the castles they built, transformed England and helped impose Norman rule. Norman clergy dominated the Church, and monasteries and churches were constructed in the new Romanesque or Norman style of architecture.

William’s survey of England, Domesday Book (1086), recorded a land governed by feudal ties. Every level of society was under an obligation of service to the class above. Punitive forest laws protected the royal hunting preserves, and reinforced the new regime.

NORMANS AND ANGEVINS

However, baronial revolts plagued the Conqueror and his son, William Rufus (r.1087–1100).

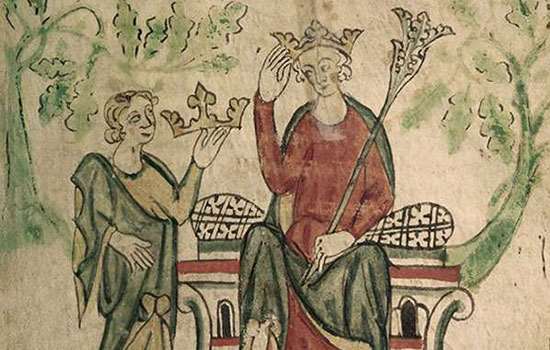

William’s youngest son, Henry I (r.1100–35), brought peace and administrative and legal reform. But the country descended into chaos and civil war when Henry’s nephew Stephen (r.1135–54) was crowned king, despite the rival claim of Henry’s daughter Matilda.

Order was restored by Matilda’s son, Henry II (r.1154–89), the first of the Angevin or Plantagenet kings. A monarch of boundless energy and ungovernable rages, he travelled constantly through his vast dominions, stretching from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees. The many fortresses he raised included Dover Castle, which was rebuilt partly as a splendid stopover on the road to Canterbury and the shrine of his ‘turbulent’ priest, St Thomas Becket, murdered in his cathedral by Henry’s knights in 1170.

Henry’s later reign was clouded by his fraught relationship with his sons and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine. When he died in France in 1189 he was at war with his eldest son, Richard, who had joined forces against him with the French king.

MAGNA CARTA

Richard I ‘the Lionheart’ (r.1189–99) was always abroad or on crusade. His younger brother John (r.1199–1216) was forced by his barons to sign Magna Carta (the ‘Great Charter’), which was intended to limit his powers, in 1215. But ultimately he ignored it. His incensed barons invited Prince Louis of France to invade in May 1216. John died in October 1216, with his nine-year-old son, Henry, assuming the throne in the midst of French invasion.

Louis conquered almost all of south-eastern England (though not Dover Castle), but retreated in 1217 after defeats in the Battle of Sandwich and in the streets of Lincoln.

KINGS, BARONS AND FAVOURITES

The long reign of Henry III (r.1216–72) saw further baronial unrest, from the late 1250s headed by Simon de Montfort. But after de Montfort’s death at the Battle of Evesham (1265) and the long siege of Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, rebellion was finally suppressed. This was a time when chivalric ‘heraldry’ blossomed, enhanced by the craze for legends of King Arthur.

Edward I (r.1272–1307), another great castle-builder, united his barons behind the conquest of Wales (1277–84) and his attempts on Scotland. His Scottish policy proved disastrous for his less warlike son Edward II (r.1307–27), though, whose defeat at Bannockburn (1314) was followed by Scots raids far south of the border.

The king’s devotion to his low-born ‘favourites’, Piers Gaveston and then the Despenser family, enraged his barons. So when Edward’s spurned wife, Isabella, and her lover, Roger Mortimer, invaded from France in 1326, they quickly gained support. Edward was forced to renounce the throne in favour of his 14-year-old son, and was almost certainly brutally murdered at Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire.

Although Isabella and Mortimer initially governed, Edward III (r.1327–77) assumed control in his own right in 1330, ousting his mother and executing her lover.

Edward was a great warrior king, winning victories in France at Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356) during the early years of what was later known as the Hundred Years War (1337–1453). His armies included archers using longbows, which became the dominant English weapon of the later Middle Ages.

CHURCH AND SOCIETY

Monasteries and churches flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. New religious foundations such as almshouses and hospitals cared for the poor and sick.

Towns grew in size and autonomy, as the old divisions between Normans and the English began to break down. English began to replace Norman French as the dominant language. Commerce developed, helped by better coinage and the growth of the wool trade. But the growth of a money-based economy began to put the old feudal order under pressure.

PLAGUE, REVOLT AND PIETY

Then, in 1348–9, the established order and the population were struck a devastating blow by the Black Death, which killed between a third and a half of England’s population.

The most immediate of its many effects was an acute labour shortage. Survivors demanded higher wages and bond men refused to do unpaid ‘service’ for feudal masters. Attempts to fix wages and prices at pre-plague rates only increased resentment.

Edward III’s grandson and successor, Richard II (r.1377–99), inherited a bankrupt treasury and discontent over reverses in the conflicts with France. In 1381 simmering grievances erupted into the Peasants’ Revolt.

The feudal system was not the only institution being challenged. For the first time in English history, the doctrines as well as the actions of the Church were being attacked, by John Wycliffe and the Lollards. Yet still religion remained all-pervasive in daily life, though the focus of piety changed from monasteries to parish churches. Many people sought salvation by paying to have prayers said for them in chantry chapels, and undertaking pilgrimages.

ROYAL UPHEAVALS

In 1399 Richard II was deposed and murdered by Henry IV (r.1399–1413), the first of the many upheavals to afflict the monarchy during this period. Though assailed from many quarters, Henry held onto his throne, and his Lancastrian dynasty was reprieved by the achievements of his son.

The greatest of all English warrior kings, Henry V (r.1413–22) won a startling victory over the French at Agincourt in 1415, achieved largely thanks to the all-conquering English longbow. By the time of his premature death he was ruling half of France.

The Wars of the Roses

More dangerous was the increasingly fashionable expression of power and status through the recruiting of private armies of liveried retainers. These contributed to the breakdown of order as Henry VI (r.1422–61 and 1470–71) proved incompetent to rule, and rival aristocratic factions contended to control both monarch and kingdom.

These feuds developed into a series of short campaigns (and often bloody battles) fought at intervals between 1455 and 1485, during which the Crown changed hands six times. Cannon were used in some sieges, but the longbow remained the dominant weapon.

The Yorkist Edward IV (r.1461–70 and 1471–83) eventually emerged victorious. But his brother Richard III (r.1483–5) alienated supporters by seizing the throne from his nephew Edward V (r.1483). Richard was defeated and killed at Bosworth (1485) by the Lancastrian heir, Henry Tudor.

Medieval stories

-

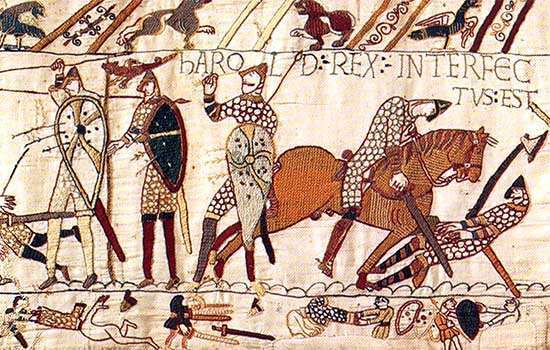

What Happened at the Battle of Hastings?

In the early morning of 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Find out what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

Piers Gaveston and the Downfall of Edward II

Discover how Edward II’s reliance on his ‘favourites’ and possible lovers led to his abdication and death.

-

The Massacre of the Jews at Clifford's Tower

One of the worst anti-Semitic massacres of the Middle Ages took place in York in 1190. The city’s entire Jewish community was trapped by an angry mob inside the tower of York Castle.

-

Lord Hastings, Richard III and an Unfinished Castle

How William Lord Hastings’s ultra-fashionable castle at Kirby Muxloe, Leicestershire, was left incomplete following his summary and shocking execution by the future Richard III.

-

Richard of Cornwall, King Arthur and Tintagel Castle

Why did Richard, Earl of Cornwall and one of the richest men in Europe, swap three castles for a rock?

-

Where Did the Battle of Hastings Happen?

Historians have long accepted that Battle Abbey was built ‘on the very spot’ where William the Conqueror defeated King Harold. Is there any truth in claims that the battle took place elsewhere?

-

The Misbehaving Monks of Hailes Abbey

Visitation records from abbots who came to inspect Hailes Abbey offer tantalising glimpses into the lives of the monks who lived there and the vices that may have tempted them.

-

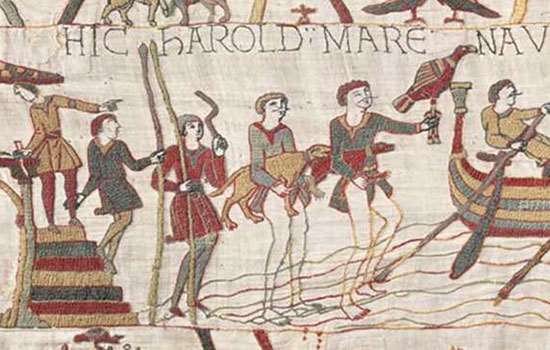

A Canterbury Tale: The Bayeux Tapestry and St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine’s Abbey has long been celebrated for its contribution to English Christianity. But could it also be the birthplace of one of the most famous artefacts in history?

More about medieval England

-

Medieval: Architecture

For more than a century after the Battle of Hastings, all substantial stone buildings in England were built in the Romanesque style, known in the British Isles as Norman. It was superseded from the later 12th century by a new style – the Gothic.

-

Medieval: Religion

The Church was a pervasive force in people’s lives, with the power and influence of the Catholic Church – then the only Church in western Europe – reaching its zenith in England in the Middle Ages.

-

Medieval: Warfare

The Norman Conquest was achieved largely thanks to two instruments of war previously unknown in England: the mounted, armoured knight, and the castle.

Read More

-

Previous Era: Early Medieval

The six and a half centuries between the end of Roman rule and the Norman Conquest are among the most important in English history. This long period is also one of the most challenging to understand – which is why it has traditionally been labelled the ‘Dark Ages’.

-

Next Era: Tudors

England underwent huge changes during the reigns of three generations of Tudor monarchs. Henry VIII ushered in a new state religion, and the increasing confidence of the state coincided with the growth of a distinctively English culture.