Romans: Landscape

Farming had been around in Britain for some 4000 years by the time of the Roman conquest, so much of the natural wildwood that once covered these islands had already been cleared. The landscape the Romans found was one of cultivated fields and pastures, scattered farmsteads and settlements, and surviving islands of managed woodland.

Roads and Towns

The Romans eventually criss-crossed the landscape with roads, beside which many villages and towns developed. These often had rectangular houses and shops fronting onto the road.

Travellers along the roads between towns would have seen clusters of traditional British roundhouses. These would have been increasingly interspersed, or replaced as the years went by, with the white plaster rendering and red-tiled roofs of villas, as landowners built Mediterranean-style farmhouses.

ESTATES AND URBAN ISLANDS

A patchwork of small family farms gave way to extensive and intensively exploited estates. Some of these were privately owned by British aristocrats who prospered under Roman rule; some were parcelled out to army veterans; and others (‘imperial estates’) were owned directly by the emperor and run on his behalf by bailiffs.

A distance of more than 50 miles – maybe a three- or four-day journey – separated the major cities, which must have been an astonishing sight for country dwellers. From the mid-2nd century walls protected these urban islands, as at Verulamium, now St Albans, in Hertfordshire.

VILLAS IN THE LANDSCAPE

The villa-builders adopted the Roman aristocratic ideal of a pleasurable and leisured country life, and this is reflected by the way villas were often built with a beautiful view of the landscape. This is particularly apparent at Great Witcombe in the Cotswolds, which sits on a hillside overlooking a wooded valley.

The immediate surroundings of larger villas were often beautified with formally planted gardens (as at Chedworth in Gloucestershire, and Fishbourne in West Sussex), though few examples of these can now be seen. But the magnificence of villas like Lullingstone in Kent was only possible because of the productive estates that surrounded them, although we have comparatively little archaeological evidence of these.

A landscape of villas and small towns (the two are always found together) only fully developed in the fertile lowland areas of southern, midland and eastern Britain – although more villas have been found recently in west Wales, and in the north-east extending almost as far north as Hadrian's Wall.

NORTHERN MILITARY ZONE

In much of the north-west (Lancashire and Cumbria) there are no known villas. Here, traditional pre-Roman settlements seem to have endured, unchanged, for much longer. There was a correspondingly greater military presence, and at intervals along the roads we find long-lived Roman forts like Ambleside in the Lake District, a reminder that the surrounding hills may have harboured long-standing resistance to Roman rule.

The neighbouring fort of Hardknott, in its mountain pass, is one of the most strikingly preserved and situated forts in the empire, although it was occupied only for a brief period in the reign of Hadrian (AD 117–38).

The remoteness of the north also means that there has often been less damage to the archaeological record from medieval and modern agriculture than elsewhere. Sometimes the surrounding landscape remains little changed from Roman times. Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall is the only fort in the empire where, as well as the buildings of an attached civilian town (or vicus), cultivation terraces (on the south-facing slope outside the fort) and the earthworks of cultivation plots (to the west) can be seen.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.

Roman Stories

-

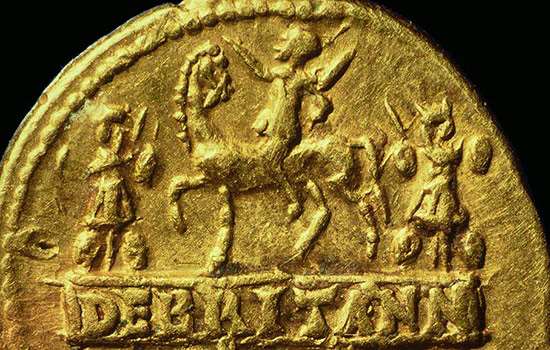

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

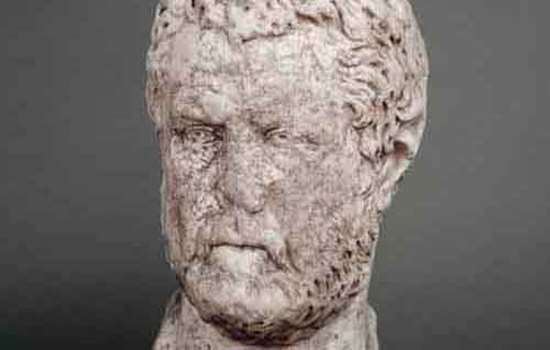

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.