Stuarts: War

One result of the devastating Civil Wars of 1642–51 was the reorganisation of the Parliamentary army using European principles. Indeed, from 1660 the restored Charles II used the New Model Army as a blueprint for his small, professional and increasingly successful force. This was the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.

DANGEROUS NEGLECT

James I’s peaceful foreign policy meant drastic cutbacks on military and naval expenditure. With the English and Scottish crowns united, border warfare ceased and defences were run down: Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle was sold and the enormous town defences neglected, while castles such as Norham fell into decay.

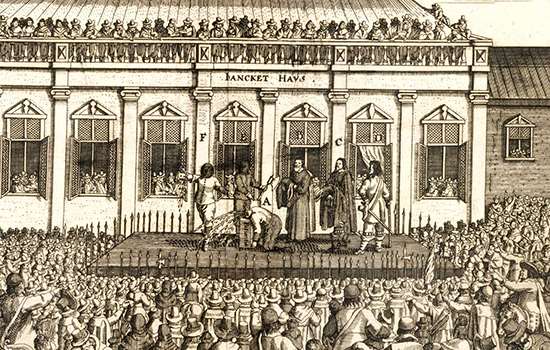

This neglect, coupled with poor leadership, led to catastrophic failure when James eventually sent an army to war against Spain at Cadiz in 1625, and when his son Charles I attacked the French at La Rochelle in 1627–9. Likewise, when Charles, in defiance of Parliament, invaded Scotland in an attempt to impose religious reforms there in 1639–40, he met with humiliation and defeat.

The curtain was raised on civil war, which erupted in England two years later. The devastating Civil Wars of 1642–51, for which the country was completely unprepared, affected almost every corner of the British Isles.

AMATEUR FORCES

While both sides – King and Parliament – had commanders with experience of warfare on the Continent, such as Charles I’s nephew, Prince Rupert, some brilliant leaders (such as Oliver Cromwell) had no such experience at all.

The troops were at first mainly part-time, locally trained militia whose capabilities varied enormously. Consequently fighting was regional and variable in skill, scale and intensity, and most professional soldiers were foreign.

NEW MODEL ARMY

Change came when Parliament established a New Model Army in 1645, permanent, well-trained and drilled to fight anywhere. This proved to be the decisive force in the wars, from its first win at Naseby (1645) to its final victory at Worcester (1651).

Aside from a few large set-piece battles, the Civil Wars witnessed fragmented warfare with savage, small-scale fighting and siege work. In battle, the New Model Army adopted effective ‘all arms’ methods which had been filtering into England from the Continent and involved co-ordinating infantry, artillery and cavalry in rapid, flexible warfare.

By the 1680s flintlocks had effectively replaced the old matchlocks as the most common type of personal firearm. By the 1700s the pike had disappeared and English infantry were equipped with flintlock muskets and bayonets. Lighter and more efficient cast-iron artillery slowly replaced brass. By 1714, heavy guns were being standardized by calibre.

THE NAVY

Charles I had begun to build up the fleet after 30 years of stagnation, albeit through his bitterly controversial tax ‘Ship Money’ (1634).

Seized by Parliament during the ensuing Civil Wars, the fleet proved an invaluable asset. A powerful force during the First Dutch War (1652–4), it foundered again after the Restoration so that two further naval wars against the Dutch (1665–7 and 1672–4) met with varying success and witnessed the humiliating Dutch raid on the Medway (1667), when a chunk of the English fleet was caught in the lea of Upnor Castle, Kent. Only after William III’s accession in 1688 did the navy begin to flourish again.

FORTIFICATIONS

The Stuarts built few forts in England before the 1640s, with Suffolk’s Landguard Fort (1620s) a rare exception.

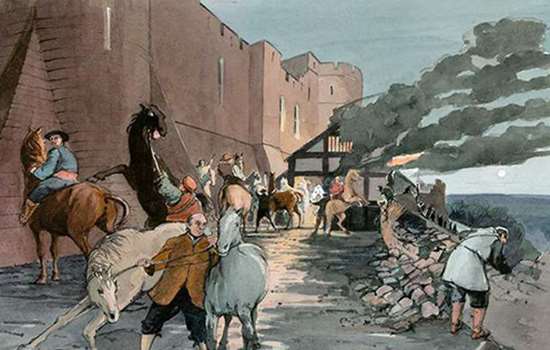

Bastioned fortifications in key towns and strategic ports proliferated during the Civil Wars, and survive at Garrison Walls, St Mary’s (Scilly) and Tresco (Scilly). Castles and manor houses were also fortified and some, such as Goodrich (Herefordshire), Sherborne Old Castle (Dorset) and Pendennis (Cornwall) played significant regional roles. Scarborough Castle in North Yorkshire endured a sensationally fierce siege.

Others, including Farleigh Hungerford Castle (Somerset) and Moreton Corbet and Stokesay (both Shropshire), housed small garrisons which controlled the surrounding country. After the war many fortifications were deliberately destroyed.

In 1660 Charles II employed the Dutch engineer Sir Bernard de Gomme to implement a programme of fortress construction, using bastioned artillery defences concentrated on the naval bases and rivers. Fine examples survive at Tilbury Fort, Essex, and Plymouth Citadel, Devon, both completed during the 1670s and 1680s.

BIRTH OF THE BRITISH ARMY

Charles II disbanded the New Model Army but created a small professional force of some 9,000 men, despite English distaste for standing armies. The ‘Guards and Garrisons’ based in London and at coastal fortifications represent the beginning of the British Army tradition.

In 1689 the existence of the army and its loyalty and discipline were regulated by the first Mutiny Act; a new act had to be passed by Parliament each subsequent year, thereby ensuring that the army was controlled by the law of the land. In 1707 the English and Scottish armies, until then separate, were amalgamated.

This army, supplemented by local militia, fought at home, easily crushing Monmouth’s rebellion at Sedgemoor (1685) under James II. It was engaged in Ireland (1689–91) after the accession of William III, where it was supported by Dutch and Irish Protestant soldiers, and in Scotland with some Dutch and Scottish support during the first short-lived Jacobite uprising (1689–92). Increasingly it served in Europe, America, the West Indies and India, notably during the Nine Years War (1688–97) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14).

By 1714, British soldiers had gained a fearsome reputation. As part of a coalition commanded by John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, they had inflicted a series of defeats on the ‘invincible’ French armies of Louis XIV.

Stuarts Stories

-

The English Civil Wars

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

-

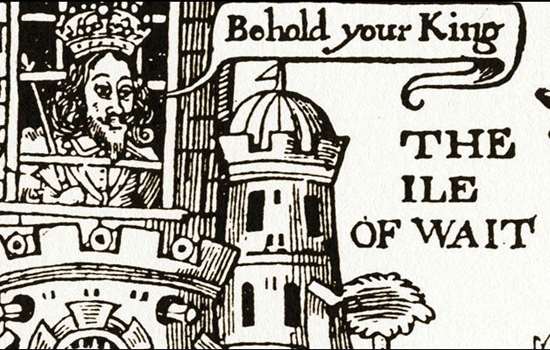

Charles I: a Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle

Learn about Charles I’s time as a prisoner of Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.

-

The Siege of Goodrich Castle

In June and July 1646, Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the Civil War.

-

THE SIEGE OF DONNINGTON CASTLE

Discover how Donnington Castle in Berkshire held out for Charles I during a 20-month siege in 1644–6, and played a key role in the Second Battle of Newbury.

-

Charles II and the Royal Oak

How the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War in 1651, giving English history one of its greatest adventure stories.

-

Blanche Arundell, Defender of Wardour Castle

Read about how Lady Blanche Arundell heroically led a small band of men and women in defence of her home, Old Wardour Castle, when it came under siege during the Civil War.

-

The King and his Favourite

George Villiers became a favourite of King James I after their first meeting at Apethorpe in 1614. Read about James and George and the surviving love letters between them.

-

Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was one of the most prolific female authors and philosophers of the 17th century, writing at a time of immense political upheaval.

More about Stuart England

-

Stuarts: Architecture

From the grand country houses of the early Stuart period to Christopher Wren's new churches that rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

-

Stuarts: Commerce

The economy of much of Stuart England was largely based on traditional industries. London, however, was at the centre of a growing international network of trade.

-

Stuarts: Parks and Gardens

The influence of the great formal gardens of the Renaissance gradually gave way to the opulence of the Baroque during the Stuart period.

-

Stuarts: War

How the reorganisation of the Parliamentary army following the devastating Civil Wars of 1642–51 was the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.