Tudors: Parks and Gardens

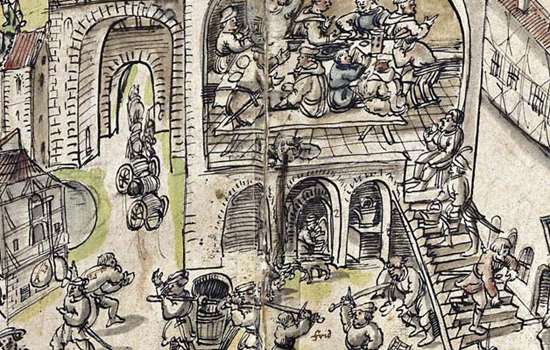

Tudor parks and gardens provided an opportunity for dramatic displays of newly found wealth, success and power. Particularly during Elizabeth I’s reign, elaborate formal gardens and extensive pleasure grounds became essential accessories of fashionable mansions.

PARKS AND PASTIMES

In the early 16th century aristocratic landowners used their deer parks to cement social and political relationships by offering guests the chance to hunt. At Framlingham Castle, Suffolk, for example, the park was carefully managed, and detailed accounts record the wide variety of visitors, from the prioress of nearby Campsey Priory to courtiers such as Cardinal Wolsey and ‘the French Queen’ (Mary, sister of Henry VIII). Lodges within these parks provided informal accommodation away from the main house.

Increasing pressures for land in the second half of the century, however, led to some deer parks being converted into productive farmland. Others continued to be used as secluded reserves around the fashionable residences which were now being built. Whole villages were sometimes removed and their former fields enclosed for private use.

FORMALITY AND DISPLAY

Just as landowners used their deer parks to make grand statements and promote their status, so in their gardens they combined different elements to display their aspirations, while also enhancing the visitor’s experience.

Owners of stately homes regarded their gardens as extensions of their houses: places to display their pedigree, to entertain and to feast. So the architecture and setting of houses were linked in increasingly elaborate schemes that incorporated imposing terraces, fountains, moats and canals, topiary and statues.

This approach was complemented by planting schemes that benefited from many newly introduced species. A love of flowers was fast becoming a national characteristic, and a great variety of trees were often arranged within ornamental orchards, as well as compartments containing decorative flowerbeds or knots. The latter ultimately developed into complex interlaced patterns.

RENAISSANCE INFLUENCES

The adoption of ideas of order and harmony from French and Italian Renaissance gardens led to an emphasis on alignment and symmetry, together with the mixing of classical motifs with existing medieval forms. By using geometry to create a regular layout, owners could demonstrate their ability to shape and control nature, in addition to projecting an image of their importance and authority.

The development of specific routes and different plantings through a succession of individual garden spaces allowed a range of narratives and imagery to be presented. The variety of associations and allusions on offer extended from the amorous to the ancestral, and mixed mystery and myth with the metaphysical.

SENSUALITY AND THEATRE

The overall effect of meaningful layers of sensual planting, grandiose architecture and formal arrangement was one of conspicuous splendour.

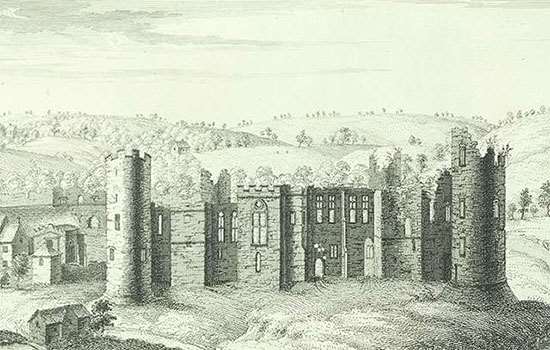

It created a theatrical setting suitable for pageantry and spectacle, one particularly striking example being Robert Dudley’s entertainments for Elizabeth I at Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, in 1575, which incorporated the entire landscape in a continuous narrative of events and tableaux.

Tudor stories

-

The Suppression of Roche Abbey

How a vivid eyewitness account reveals the shocking speed and scale of destruction of Roche Abbey after the Suppression of the Monasteries.

-

Walter Hungerford and the 'Buggery Act'

In 1533 Henry VIII’s government introduced the ‘Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie’. Less than ten years later, Walter Hungerford became the first man to be executed under its terms.

-

Lady Anne Clifford

The last member of one of England’s great medieval dynasties, Lady Anne Clifford became something of a legend in her own lifetime.

-

Lydford Law and Parliamentary Privilege

From a Tudor ‘tinner’ to a 21st-century footballer: how the Privilege of Parliament Act can be traced back to the ghastliness of prison life at Lydford Castle in Devon.

-

The Rise and Fall of a Tudor Wool Factory

How the Heydon family of Baconsthorpe Castle in Norfolk made a fortune from the East Anglian wool trade – and then lost it all.

-

Mary Queen of Scots at Carlisle Castle

Find out why, after Mary Queen of Scots fled to England in 1568, her two-month stay at Carlisle Castle began 19 years of captivity.

-

Bess of Hardwick

Rising from a modest background to become one of the richest women of her time, Bess was also a tireless and ambitious builder, whose houses symbolised her rise to wealth and power.

-

Sir Peter Carew and Dartmouth Castle

How a centuries-old stand-off over a castle provoked Tudor soldier and adventurer Sir Peter Carew into trying to outwit the borough of Dartmouth.

-

Lambert Simnel and Piel Island

How a Yorkist claimant to the English throne failed to usurp Henry VII in the final chapter of the Wars of the Roses.

More about Tudor England

-

Tudors: Parks and Gardens

Tudor parks and gardens provided an opportunity for dramatic displays of newly found wealth, success and power.

-

Tudors: Architecture

The architecture of early Tudor England displayed continuity rather than change. Later, however, the great country house came into its own.

-

TUDORS: RELIGION

The Tudor era witnessed the most sweeping religious changes in England since the arrival of Christianity, which affected every aspect of national life.

-

Tudors: War

The Tudor period saw England's medieval army evolve into a larger, firearm-wielding force supported by powerful ships and formidable gun forts.