The Founding of Cleeve Abbey

Between 1186 and 1191 William de Roumare, Earl of Lincoln, gave all his lands at Cleeve for the foundation of a Cistercian abbey.

The first abbot and his monks arrived in 1198 from Revesby Abbey in Lincolnshire, which had itself been founded by William’s grandfather. Cleeve was originally called ‘Vallis Florida’ (valley of flowers) and it soon attracted further gifts, mainly of land, from other local aristocrats.

When William founded the abbey, it was partly out of religious belief and partly out of self-interest. Founding an abbey was expensive, but medieval people believed that many prayers were needed to avoid a long stay in purgatory, or worse still descent into hell. It was thought that the best people to pray were the men and women – monks and nuns – who led a perfect Christian life dedicated to God.

The Cistercian way of life

The monks of Cleeve followed a strict daily regime. Although their standard of living rose over the centuries, they kept to the main principles of monastic life.

The Cistercian order, to which Cleeve belonged, was one of the most successful monastic reform movements of the Middle Ages. The monks who founded the order in 1098 wanted to return to a strict interpretation of the Rule of St Benedict (which was followed by most monasteries in western Europe), with a simplified lifestyle and services. Cistercian monks were expected to spend about a third of their waking hours in church for the eight daily services, a third working – in manual labour, or perhaps copying manuscripts – and a third reading sacred texts.

They had to get up for night services, wore a rough, undyed wool habit, were only allowed one meal a day in the winter, and weren’t allowed to eat meat. This austerity was also reflected in their buildings, which were often far plainer than those of other orders of monks or canons. As time went on, however, in common with the outside world, the conditions became less harsh, and Cistercian abbeys became more like those of other orders.

However, the monks of Cleeve kept up the tradition of manual labour right to the end. We know this because a remarkable account survives from 1589 by farmers who were over 80 years old, who describe how the monks wore out their gloves pulling up broom plants.

Find out more about medieval monksBuilding the monastery

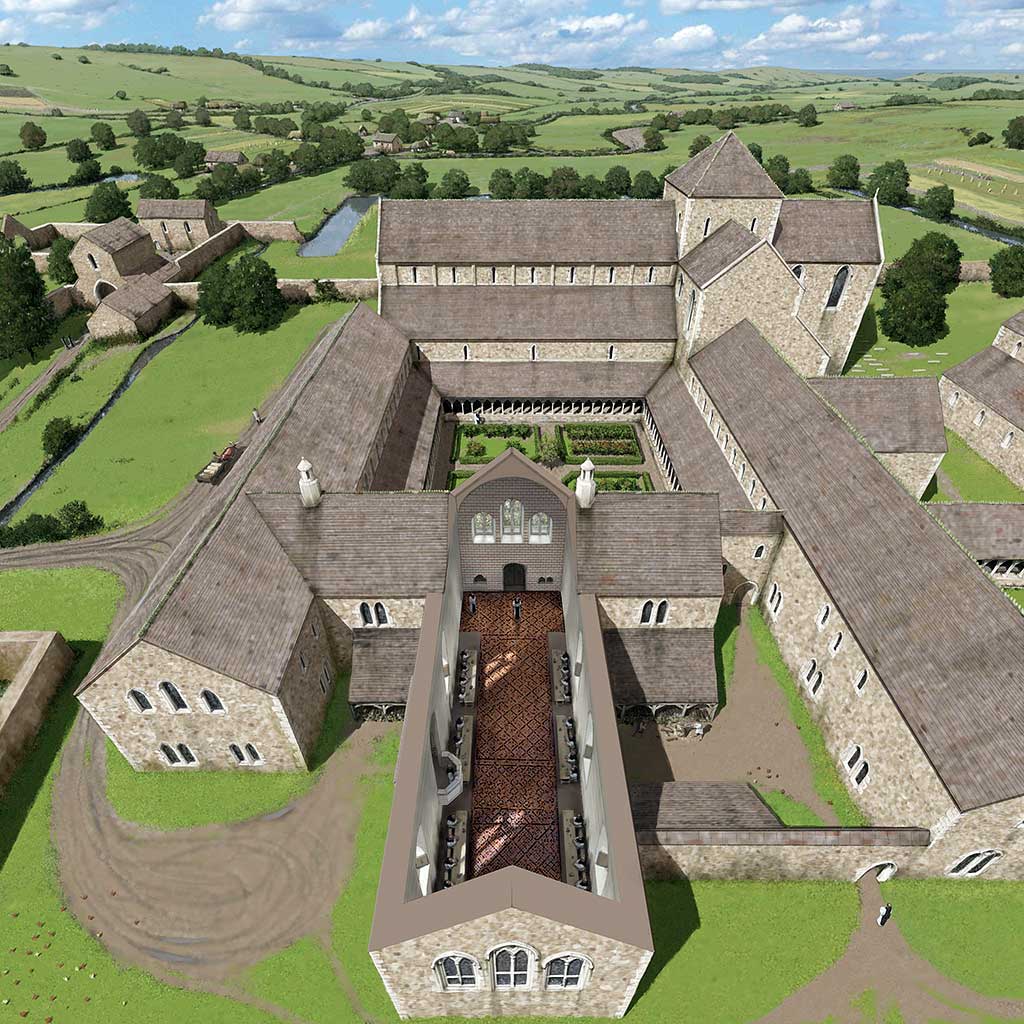

All the main buildings for the monks were erected shortly after the abbey was founded. The whole monastery was complete by the late 13th century.

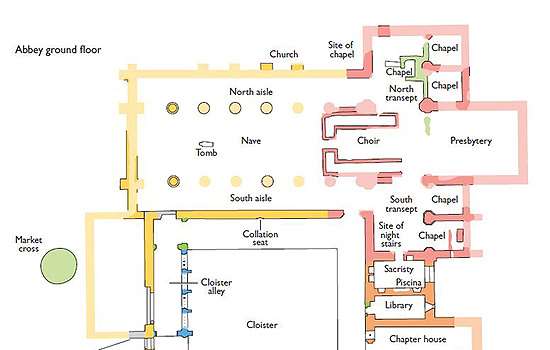

Cleeve Abbey followed a standard Cistercian layout, with the buildings used by the monks every day placed around the four sides of the cloister. The church was on the north side, with the refectory (dining hall) opposite, and the library, chapter house, parlour and day room all in the east range, with a dormitory above. Many more buildings were located away from the cloister, including guesthouses, an almshouse, barns and stables, bakehouses and brewhouses.

Some 200 years after the abbey’s completion, it was radically remodelled. By the 15th century living standards had changed, and during his 50-year rule as abbot David Juyner started updating the monastery to reflect this. Private chambers were created for the monks and a new refectory was built, in imitation of the hall of a secular lord, with offices and rooms for the abbot at one end.

In the 16th century Cleeve’s last abbot, William Dovell, completed the renovations with a remodelling of the great gatehouse, a new west cloister alley and a further extension of the abbot’s lodgings into the upper rooms of the west range.

Adorned with glory

One of the special features of Cleeve is the exceptional amount and quality of the surviving decoration on the walls and floors.

The founders of the Cistercian order took an extremely austere approach to art and architecture and rejected almost all forms of decoration, including brightly coloured and figurative wall painting. The interiors of early Cistercian abbeys were simply limewashed, with white or grey paint used to simulate masonry lines. The only image was a painted figure of the crucified Christ.

However, the order’s attitude to the use of ornament, including wall painting, gradually evolved. By the late 12th century, black and red paint was being used to simulate masonry lines, a common form of decoration at this time. Fragments of red-line painting dating to the early 13th century can be seen in several of the buildings at Cleeve. They include masonry patterns, scrolls, rosettes and foliage.

The monks’ buildings also had fine tiled floors. The 13th-century tiled floor in the old refectory is one of the most complete in Europe and uses a mixture of heraldic, geometrical and foliage designs.

By the 15th and 16th centuries, restraint had been abandoned. In place of decorative motifs, large figurative and devotional pictures covered entire walls. The allegorical wall paintings in the abbey’s painted chamber give an idea of the extent and variety of subject matter of late medieval wall painting at Cleeve.

Cleeve’s painted chamber

The painted chamber at Cleeve (which was probably the office of the abbot, where his clerks worked) derives its name from the large, late 15th-century wall painting that covers one wall.

Unparalleled elsewhere in Britain, the painting shows a richly dressed, bearded old man praying on a bridge. He is flanked on one side by a lion and St Catherine of Alexandria (holding a wheel, the symbol of her martyrdom) and on the other side by a dragon and St Margaret of Antioch (who is impaling a second dragon with her staff). Fishes and large eels swim in the water below the bridge, while flying angels are represented in black and red outline, holding instruments of Christ’s Passion – the crown of thorns and the scourge.

The subject of the painting has recently been identified as the legend of a man crossing a bridge from the Gesta Romanorum (‘Deeds of the Romans’), a popular medieval collection of religious tales.

Follow the link below to find out how you can help English Heritage conserve its important collection of wall paintings.

save our wall paintingsWorking with the landscape

To be self-sufficient, abbeys needed to own a great deal of land, and to make the most efficient use of it.

The lands of Cleeve supplied wood, charcoal, wool, fish and rabbits, as well as crops such as wheat, barley, rye, oats and beans. The lands were divided into self-contained farms, known as granges – Cleeve had five main granges, all close to the abbey itself. The monks also raised money from their mills, and from their Right of Wreck, granted by Henry III in 1232, which enabled them to claim the contents of ships wrecked along their coastline.

The Cistercians opened up monastic life to the uneducated by introducing a new category of religious men called lay brothers to work on their estates. By helping to manage the estates and by working the lands directly, these men also freed the monks for a life of prayer and worship. As living standards improved in the outside world, fewer and fewer men chose to lead this form of religious life, in which they were, in all but name, unpaid servants. By the time Cleeve Abbey was suppressed, and probably well before that, four of the five granges were rented out.

The abbey’s suppression

In the 1530s Henry VIII put an end to medieval monasticism in England. In 1533 he declared himself head of the English Church to resolve his dispute with the papacy over his divorce from Catherine of Aragon. He then instituted a survey to value all church property, followed by an inquiry into the standards of religious life in the monasteries. In 1536 an Act of Parliament closed all monasteries with an income of less than £200. Cleeve was one of these.

Henry VIII’s pressing need for money meant that many monastic estates were quickly sold or leased to new owners. In 1528 the king sold Cleeve’s buildings and lands to the Earl of Sussex as a reward for his service in quelling the Northern Rebellion against the Suppression of the Monasteries.

The abbey church was swiftly demolished so that it could no longer be used for services, but unusually some of the cloister buildings were left relatively intact.

Those parts previously used as the abbot’s lodging were lived in as a private manor house by wealthy tenants, with the refectory serving as the great hall. In the 17th century, the status of the tenants declined from gentry to yeoman farmer. A modest farmhouse range was built at the south-west corner, the rooms of the abbey and mansion were used as farm buildings and the cloister served as a farmyard.

John Hooper, martyr

One of the last monks at Cleeve was John Hooper (1495/1500–1555). A Somerset man, he had graduated from Oxford University in 1519, and may have entered Cleeve at this time. After leaving the monastery he obtained employment in the household of Thomas Arundell in 1537, and it was during this time that he encountered the works of religious reformers such as Ulrich Zwingli and became a Lutheran. He subsequently visited a number of cities in northern Europe, including Basel and Zurich.

During the reign of Edward VI (1547–53) Hooper returned to England and preached the reformed Protestant doctrine in London. Openly hostile to traditional Catholic teaching, he was consecrated Bishop of Gloucester by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in 1551.

Following the accession of Mary I in 1553, however, the Church in England was returned to the papacy and the persecution of prominent Protestant churchmen ensued. Hooper was imprisoned and condemned as an obstinate heretic. Refusing to recant, he was burned at the stake in Gloucester on 9 February 1555, ‘for the example and terror of others’.

Image © National Portrait Gallery, London

From farm to monument

Cleeve Abbey continued to be used as a farm into the 20th century, but from as early as the mid-18th century it was being appreciated as an historic monument.

George Luttrell, of Dunster Castle, bought the site in 1868 and set about preserving the abbey remains. Within a few years the abbey buildings and 13 acres (5.3ha) of surrounding land were removed from the farm tenancy and tickets were sold to view it. In the early 1870s a series of excavations, which removed ‘walls, pools, mounds, farm roads and masses of filth’, gradually uncovered the church foundations. Further excavations revealed the 13th-century tiled pavement of the original refectory. The farmhouse remained occupied, and was divided into three cottages.

In 1949 the Luttrell estate was sold to pay death duties, and it passed to the Crown. The Ministry of Public Building and Works undertook a massive programme of consolidation of the fabric of the buildings, which included repair of all the roofs. The church was partially re-excavated and laid out for display.

The extraordinary survival of so many of the abbey buildings at Cleeve, together with much of their original decoration, provides an insight into how such buildings were used, changed and adapted over time that is unique in south-west England.

related content

-

Visit Cleeve Abbey

Visit the abbey to get a glimpse of monastic life 800 years ago, and see possibly the finest cloister buildings in England.

-

Buy the guidebook

This superbly illustrated guidebook, which features the latest research and new photography, includes a full tour and history of the abbey.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF ground plan to discover how the abbey developed over time.

-

Medieval monasteries

Find out more about England’s medieval monastic buildings and uncover the stories of those who lived and prayed in them.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.