Roads in Roman Britain

How, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

NEW NETWORK

Following the Roman invasion of Britain under the Emperor Claudius in AD 43, the Roman army oversaw the rapid construction of a network of new roads. These served to link the most important military places in the new province of Britannia.

Roads allowed troops to move efficiently from ports such as Richborough and Dover in Kent, and enabled officials and messengers to travel swiftly, using the imperial communications system (later known as the cursus publicus).

Many of the early roads served to link key pre-existing settlements such as Colchester in Essex and Silchester in Hampshire. These became Roman towns, and important centres for the developing Roman administration.

CORE VALUES

The structure of Roman roads varied greatly, but a typical form was an agger, or bank, forming the road’s core, built of layers of stone or gravel (depending on what was available locally). In areas of soft ground the road might be built over timber piles and layers of brushwood. The core of the agger would be covered with a layer of larger stones, if available, with the upper surface being formed from layers of smaller stones or gravel.

The full ‘road zone’ could be defined by ditches set some distance from the road, providing drainage and possibly space for pedestrians and animals.

The width of roads varied from about 5 metres to more than 10 metres. Some were far less well constructed than roads of the type described above. Less than half a mile south of the Roman town of Cataractonium (Catterick, North Yorkshire), the main Roman road north to Hadrian’s Wall, Dere Street, consisted of nothing more than successively wider spreads of gravel over a shallow agger.

FROM SOUTH TO NORTH

As Roman power extended across England, so did the road network. Eventually a system was created that linked the south coast ports to Hadrian’s Wall and even reached into what is now Scotland.

The Roman road known as the Fosse Way linked the south-west with Lincoln, having demarcated a temporary frontier in the late AD 40s when the Roman army paused before pushing further north and west. The Stanegate, which stretched from east to west between Corbridge and Carlisle, similarly marked a frontier before Hadrian’s Wall was built to the north of it in the AD 120s.

ROADS TO THE SEA

The roads built by or for the army not only served to link forts and towns as they developed, but were also essential for trade. Moving goods by water was cheaper than overland transport, however, so the road network linked with the sea and inland ports. Many of the supplies required by forts, such as Housesteads and Birdoswald on Hadrian’s Wall, would have arrived via the seaports of Carlisle and South Shields. Their journey may have continued via rivers before being completed by road.

Nonetheless, the Romans did move goods long distances by road – at least when there were no obstacles to doing so. A writing tablet from Vindolanda fort near Hadrian’s Wall records delays in receiving supplies of hide from Catterick because of the poor state of the roads.

ANCIENT TRACKS

But away from the engineered roads built by the army, much of the population would have relied on tracks that wound between fields, often following routes established centuries before. Many army supplies, as well as goods that were traded in towns, would have started their journey on these ancient tracks before reaching the major roads.

By Pete Wilson

Roman Stories

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

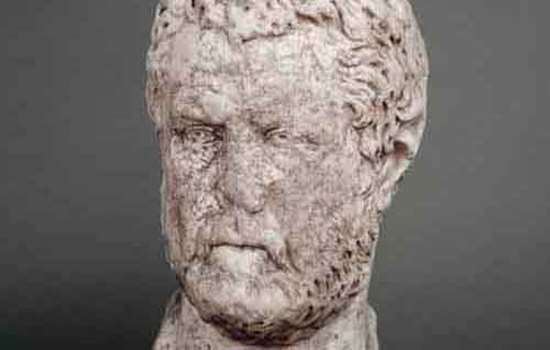

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

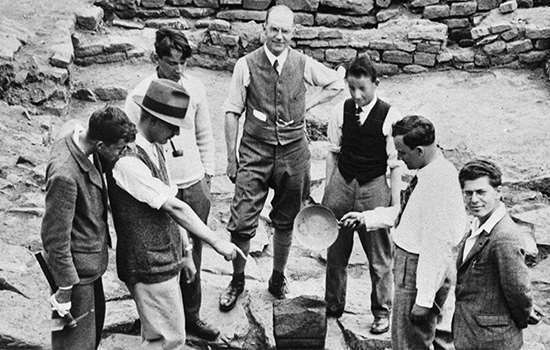

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

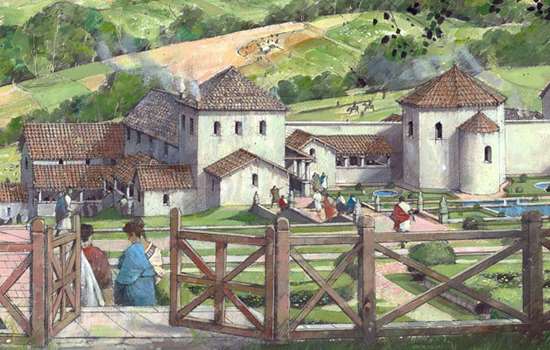

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

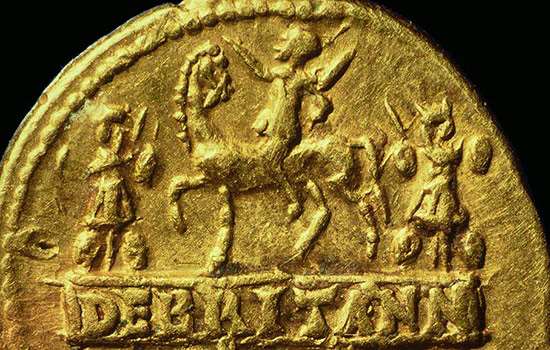

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.