Tudors: War

The Tudor period saw the gradual evolution of England’s medieval army into a larger, firearm-wielding force, supported by powerful ships and formidable gun forts to protect the country from the threat of invasion.

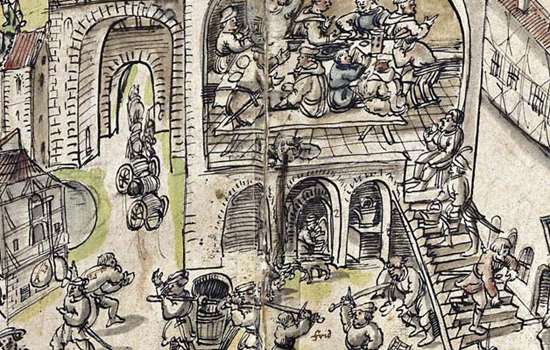

Early Tudor forces were essentially medieval. Those that fought the Scots at Flodden (1513) and the French in northern France (1511–13) did so mainly with traditional pole weapons – ‘bills’ – and still-formidable longbows.

Personal firearms were used mainly by foreign mercenaries. They were more costly, slower-shooting and less effective than a longbow in the hands of an experienced archer.

But by this time the English and their enemies had powerful artillery. Scots guns pulverised Norham Castle in Northumberland, before Flodden and Henry VIII used siege guns to great effect in France.

AGGRESSIVE FOREIGN POLICY

Henry VIII’s aggressive foreign policy took locally raised militia abroad to fight alongside specialist mercenaries.

In 1544 at least 38,000 men went to France, then the largest ever English expeditionary force. In the same period Henry deployed 5,500 men along the borders and in southern Scotland during the wars of the ‘Rough Wooing’ (1543–50) – Henry VIII’s attempt to force the marriage of his son Edward to the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, and to break the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland. Though neither venture proved successful, they provided valuable tactical experience with siege artillery, in logistics, and in combined operations between army and navy.

By 1547, English forces were slowly equipping with new personal firearms, which could be operated by less sturdy men (and after briefer training) than longbow archers. Bronze and wrought-iron artillery was commonplace, and a few cast-iron pieces were appearing on land and in warships.

Most importantly, by the end of his reign Henry VIII had built a powerful Navy Royal of warships, purpose-built to carry heavy guns, as his first line of defence against invasion. This included the ill-fated Mary Rose, which sank in 1545 during an action against the French fleet in the Solent.

CONSTANT FIGHTING

Simultaneously, English forces stood alongside the Dutch in their struggle against Spain, and with the French against Spanish encroachments. They raided Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico and fought rebellions in Ireland.

All this fighting meant that local militia were continually drafted (especially to Ireland) and new weapons and tactics were employed. Matchlock muskets and calivers replaced longbows and were used in combination with the long pike, which gradually replaced the bill. Tactically, much fighting was small-scale, consisting of surprise attacks and siege warfare, with few large battles.

NATIONAL DEFENCE POLICY

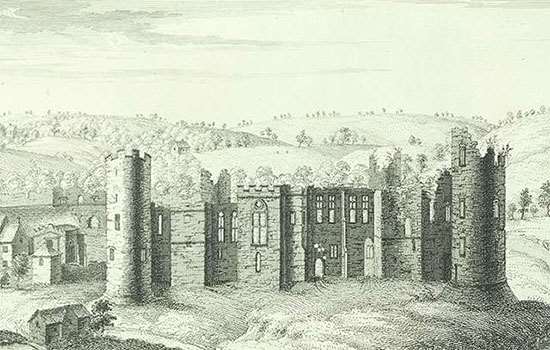

By 1500 the English were familiar with gunpowder artillery. Older castles and newer fortified houses incorporated positions for small guns, as at Berry Pomeroy, Devon, and Kirby Muxloe, Leicestershire. Prosperous towns built gun towers, notably along Southampton’s walls (15th-century) and at Dartmouth, Devon (1490s).

This local trend continued slowly, with gun towers and bulwarks at, for example, Camber, East Sussex (1512), St Catherine's Castle, Fowey, Cornwall (about 1520), Bayard's Cove (Dartmouth, 1530s) and under royal control at Berwick-upon-Tweed (1520s–30s).

Between 1539 and 1547, Henry VIII developed a national policy for defence against the possibility of an invasion by powerful Catholic forces in Europe. He built over 30 new gun forts which, working with increasingly powerful warships, were designed to prevent the capture of harbours and estuaries along the east and south coasts. The defences included small artillery ‘blockhouses’, as at Gravesend, and large forts with circular designs – examples survive at Pendennis and St Mawes in Cornwall, Portland in Dorset, Hurst and Calshot in Hampshire, Camber in Sussex, and Deal and Walmer in Kent. With characteristic squat and rounded forms, they were designed to provide massive all-round offensive and defensive firepower.

CONTINENTAL INFLUENCE

Though they proved to be a dead end in fortress design, Henry’s forts served as formidable obstacles for many years. He also experimented with what became the dominant fortress system for the next 300 years – the angle bastion – which had evolved in Italy by 1500 and spread northwards. The first English example survives at Yarmouth (1547) on the Isle of Wight.

While Upnor Castle in Kent (1559) was of outdated design, several powerful fortresses employing multiple angle bastions were built under Elizabeth I, notably at Berwick-upon-Tweed (1553–1570), Carisbrooke on the Isle of Wight (1587–1602) and Pendennis (1597–1600). Designed to resist determined siege, and influenced by European fortifications, they reflect the confidence of English engineers to adapt them at home.

More about Tudor England

-

Tudors: Parks and Gardens

Tudor parks and gardens provided an opportunity for dramatic displays of newly found wealth, success and power.

-

Tudors: Architecture

The architecture of early Tudor England displayed continuity rather than change. Later, however, the great country house came into its own.

-

TUDORS: RELIGION

The Tudor era witnessed the most sweeping religious changes in England since the arrival of Christianity, which affected every aspect of national life.

-

Tudors: War

The Tudor period saw England's medieval army evolve into a larger, firearm-wielding force supported by powerful ships and formidable gun forts.

Tudor stories

-

The Suppression of Roche Abbey

How a vivid eyewitness account reveals the shocking speed and scale of destruction of Roche Abbey after the Suppression of the Monasteries.

-

Walter Hungerford and the 'Buggery Act'

In 1533 Henry VIII’s government introduced the ‘Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie’. Less than ten years later, Walter Hungerford became the first man to be executed under its terms.

-

Lady Anne Clifford

The last member of one of England’s great medieval dynasties, Lady Anne Clifford became something of a legend in her own lifetime.

-

Lydford Law and Parliamentary Privilege

From a Tudor ‘tinner’ to a 21st-century footballer: how the Privilege of Parliament Act can be traced back to the ghastliness of prison life at Lydford Castle in Devon.

-

The Rise and Fall of a Tudor Wool Factory

How the Heydon family of Baconsthorpe Castle in Norfolk made a fortune from the East Anglian wool trade – and then lost it all.

-

Mary Queen of Scots at Carlisle Castle

Find out why, after Mary Queen of Scots fled to England in 1568, her two-month stay at Carlisle Castle began 19 years of captivity.

-

Bess of Hardwick

Rising from a modest background to become one of the richest women of her time, Bess was also a tireless and ambitious builder, whose houses symbolised her rise to wealth and power.

-

Sir Peter Carew and Dartmouth Castle

How a centuries-old stand-off over a castle provoked Tudor soldier and adventurer Sir Peter Carew into trying to outwit the borough of Dartmouth.

-

Lambert Simnel and Piel Island

How a Yorkist claimant to the English throne failed to usurp Henry VII in the final chapter of the Wars of the Roses.