Capture

The story begins on the island of St Lucia in the Caribbean.

When war between Britain and Revolutionary France erupted in 1793, the overseas colonies belonging to Britain, France and their European allies, including the Caribbean, were also dragged into the war. The many Caribbean islands were much fought over by European powers vying for supremacy. These islands were mainly inhabited by an enslaved African Caribbean population working on European-owned plantations.

A French-born revolutionary, Victor Hugues, captured the island of Guadeloupe from Britain in 1794. He then declared an end to slavery and enlisted many former enslaved and free people of mixed race into the French Revolutionary army. Across the Caribbean, men of both African and European descent served in racially integrated military units that fought against Britain – which was still a slave-owning nation – on islands such as St Lucia, St Vincent and Guadeloupe.

On 26 May 1796, the French garrison holding Fort Charlotte on St Lucia surrendered to British forces commanded by Sir John Moore. They laid down their weapons and marched out of the fort and onto British ships. The terms of their surrender ensured that they would all be treated as prisoners of war, rather than as slaves, as Moore recorded:

a flag was sent from them to know what way they might … be treated …The answer … was, that men regimented … of whatever colour, should be treated as prisoners of war.

The garrison consisted of mainly local black soldiers, with a smaller number of European French soldiers. There were also women and children among them.

The Journey to Britain

In July the ships carrying the black prisoners, as well as the British soldiers guarding them, left the Caribbean and set sail across the Atlantic towards Britain.

The Atlantic crossing was very difficult. Lieutenant-Colonel Baldwin Leighton of the 46th Regiment was in charge of the convoy and reported that both the prisoners and guards had been very sickly on the voyage. Although there were doctors on board, little could be done for the sick as the doctors ‘were in want of many necessary comforts, for the sick, on the Voyage’.

Arrival

By the time the convoy reached Portsmouth in October 1796, at least 268 prisoners and 100 British soldiers had died. In total, 2,512 prisoners had survived the journey, recorded by the Admiralty as:

- White 333

- Black 2080

- Women and children 99.

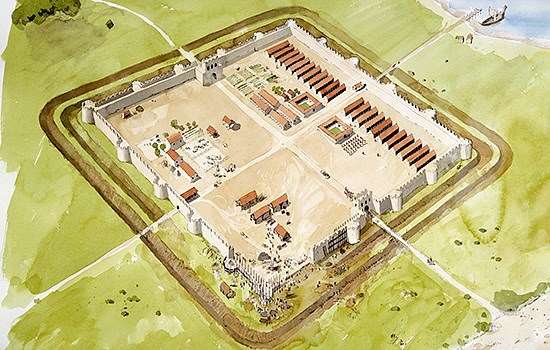

News of their arrival had preceded them. Dr James Johnston, one of the prison commissioners, went on board to prepare for the prisoners to disembark. One of the main concerns was the spread of disease, so the prisoners’ health was checked as they were taken off the ships in groups. The sick and wounded were sent to the Portchester prison hospital, which was housed in separate buildings within the castle, while healthy prisoners were placed in the main prison buildings. The women and children were also held in the prison at first, probably separately from the other prisoners, but were later sent on to Forton Prison in nearby Gosport. There they were housed in a large hospital ward.

Who were they?

The registers for the time list all the prisoners by name, including the women and children. It is difficult to find out much about their individual stories, but many would once have been slaves working on the plantations on the French and British islands of the Caribbean. Others were from the free black and mixed-race communities on the islands.

Some notable prisoners were:

- General Marinier – a free, mixed-race soldier, who had been commander-in-chief of the French forces on St Lucia and had organised resistance to British rule. He was captured on the island of St Vincent, where he had been fighting a guerrilla war, a few weeks after Fort Charlotte’s surrender

- General Marinier’s wife, Eulalie Piemont

- Jean-Louis Marin Pedre – a free, mixed-race soldier, who had been the commander of the Caribs (Garifuna), the indigenous people of the Caribbean

- Marin Pedre’s wife, Charlotte Pedre

- Captain Jean-Joseph Lambert – a free, mixed-race officer in the French army. Lambert and General Marinier had set up a guillotine on Guadeloupe, probably as a symbol of the power of Revolutionary France

- Captain Louis Delgrès – a free, mixed-race soldier, captured on St Vincent where he had been fighting alongside the Caribs, just after the surrender of Fort Charlotte.

The prisoners’ life at Portchester

Life at Portchester for the prisoners from the Caribbean was extremely challenging, because of the cold, damp weather. For many of them, this was their first encounter with a British winter. What is perhaps surprising is that they were treated with some care and consideration.

Some of the black prisoners were suffering from frostbite and many had already lost toes. Dr Johnston and the other prison officers tried to help by providing extra clothing, as many had arrived with clothes suitable for the Caribbean, not for an English winter. They were given thick woollen vests and extra socks until shoes could be made for them. A special diet was arranged which included extra potatoes and soup before bedtime. Their beer was flavoured with ginger, which was thought to be warming

Unfortunately the extra clothing had little effect – partly because, as soon became apparent, it was being stolen by the other prisoners. The prison commissioners William Otway and Dr Johnston reported that they had

been robbed and plundered by the European Prisoners, they considering themselves as a superior race of beings to the unfortunate Blacks.

Something had to be done, and quickly – every delay, Dr Johnston wrote, was ‘murdering them thru wanton cruelty’. In the end, as many of the black prisoners as possible were moved onto two newly commissioned prison ships, or hulks – the Captivity and Vigilant. These were moored in Portchester Lake, a deep water channel in the harbour outside the castle. Johnston and Otway hoped that this would provide warmer and more secure accommodation. As Dr Johnston wrote:

I went on board one of the ships this day and nothing can be conceived more comfortable and warm.

By the end of January 1797 about 1,600 black prisoners were living on the two prison ships.

Dr James Johnston

James Johnston was a qualified doctor and Royal Navy Surgeon, who worked as an inspector (or commissioner) responsible for the condition of the prisoners of war at Portchester and Forton. Many of his letters documenting the experiences of the black prisoners at Portchester survive. They reveal that, although he had no time for troublesome prisoners and staff, he was energetic, conscientious and kind, and determined to do the best he could for the prisoners under his care in difficult wartime circumstances. As he and his fellow commissioner William Otway reported in 1796:

On the proper execution of this service depends the lives and comfort of so many persons and so materially involves the Honor of the Nation, the necessity of the most rigid attention to it is too obvious to commentate on.

Image: A letter written by Dr Johnston on 8 December 1796, expressing concern that the Caribbean prisoners should be moved to the prison ships as soon as possible for the sake of their health

© The National Archives

No Parole

There were many black and mixed-race officers among the prisoners from the Caribbean.

Captured enemy officers were generally offered what was called parole when they arrived in Britain – which meant that they didn’t have to be held in one of the main prisoner-of-war prisons (usually referred to as prison depots). Instead they could live in one of the officially designated parole towns. There were over 60 of these throughout the British Isles including two, Bishop’s Waltham and Hambledon, quite close to Portchester.

When the Caribbean prisoners arrived at Portchester, the white European officers among them were placed on parole. But the black and mixed-race officers were not allowed this privilege. Both the Admiralty in London and the Commander of the Portsmouth defences, General Pitt, thought that they were too ‘violent in their behaviour, and savage in their disposition’ to be allowed among the local population. In his opinion, they were ‘very improper persons to be turned loose in any country but particularly so in this neighbourhood’.

This opinion was not shared, however, by Dr Johnston and William Otway, who wrote to the Admiralty commending the conduct of both General Marinier and a fellow officer, Captain Lambert. General Marinier was also described in a later account as being ‘very soldierly and gallant’.

In early 1797 Dr Johnston and William Otway arranged for the black officers to be sent to join the women and children at Forton Prison.

What happened to the prisoners?

Like many 18th-century prisoners of war, the men and women from the Caribbean were eventually exchanged for captured British soldiers and sent to France.

By November 1797, a year after they had first arrived at Portchester, some of the soldiers and their families began to arrive in France. General Marinier, his wife, Eulalie Piemont, and 22 others arrived in Cherbourg on 9 November. More arrived in France over the months and years that followed.

Once in France, though, the black soldiers were prevented from integrating into French European regiments. Instead, a decree of 22 May 1798 ordered that any black soldiers (and their families) who had returned to France from the colonies or from English prisons would have to go to the Île-d’Aix, off the west coast of France, where they would be formed into one company.

Life on the island was difficult – food was scarce, and many of the black soldiers had to live in tents (particularly difficult during winter). Many also had their pay reduced and were prevented from travelling to nearby Rochefort on the mainland to buy food.

Eventually, many of these soldiers became the battalion of black pioneers (Bataillon des Pionniers Noirs). In about 1806 they were sent to Italy to provide military support to the Kingdom of Naples (which had been seized by the French in 1805) and became the 7th Royal African Regiment. They fought not only in Italy but also in Russia.

It is also possible that some of the black soldiers may have been recruited from Portchester into the British Navy or perhaps the Army. The armed forces actively recruited for soldiers and sailors from the prisoner-of-war population in Britain.

A tragic end

Some of the soldiers eventually returned to the Caribbean. Captain Louis Delgrès, who like the others had initially gone to France, returned in 1799, where he became disillusioned when Napoleon attempted to re-establish slavery on the French Caribbean islands. He took up arms again, this time against France, and carried out a successful campaign. But eventually he and about 400 followers were surrounded at Matouba in Guadeloupe.

Realising there was no escape, and with French forces closing in, on 28 May 1802 Delgrès and his followers lit the gunpowder stores and blew themselves up rather than be captured and enslaved. Some were taken alive from the rubble and executed.

There is now a memorial to Delgrès on Guadeloupe and an inscription honouring him in the Panthéon in Paris, where distinguished French citizens are buried or commemorated.

The prisoners who were transported thousands of miles across the Atlantic to Portchester in 1796 are an important – and until now untold – part of the castle’s history, as well as the history of race and diversity in Britain. But they have international significance too, because of the role they played in the struggle against slavery in the Caribbean, where they had taken up the ideals of the French Revolution and fought for their freedom. Their cause was too radical for the powers governing the Caribbean at the time. But it could be argued that in some small way their imprisonment at Portchester Castle, where they were treated as prisoners, not slaves, allowed them to continue their struggle for equality and recognition.

Find out more

-

Black people in late 18th-century Britain

How much do we know about other black people living in Britain around the time the prisoners from the Caribbean were being held at Portchester?

-

Prisoners of war at Portchester Castle

During the wars with France between 1793 and 1814, thousands of prisoners of war were held at Portchester Castle. Where did they come from, and what was life like at the castle?

-

History of Portchester Castle

Read a full history of the castle, from its origins as a Roman fort, through its development as a medieval castle and its role as a prison, to the present day.

-

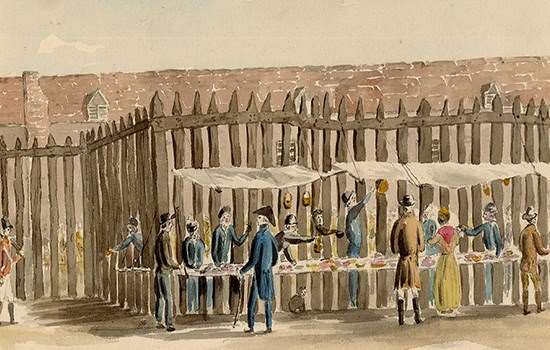

The prisoners' theatre at Portchester Castle

Find out about the theatre set up and run by French prisoners of war at Portchester Castle between 1810 and 1814.

-

Listen to Speaking with Shadows

In the episode of our Speaking with Shadows podcast, Josie Long visits Portchester Castle to learn about the black prisoners of war who were imprisoned there in the 18th century.